For the 10th year in a row, dozens of people gathered on the longest night of the year to remember District residents who died without a home, often without fanfare or memorial services.

This year’s Homeless Memorial Vigil, held in freezing weather on Dec. 20 and 21, honored the at least 77 individuals in D.C. who died while experiencing homelessness in 2022. Organized by the People for Fairness Coalition (PFFC), a group of Washingtonians who have experience with homelessness, the 24-hour remembrance featured a memorial service, march, and overnight sleep-in in a large white tent in Freedom Plaza.

“The event symbolizes our efforts to promote housing for unhoused people,” said Andrew Anderson, outreach director for PFFC. “This tent we’re under represents tents unhoused people use to stay warm.”

As they do each year, organizers called for the D.C. government to quickly improve its homeless services system and prevent the deaths of people without homes. Calls for change focused largely on the voucher system — over half of the people who died this year were in the process of obtaining housing through a voucher, according to PFFC numbers. Though D.C. has funded nearly new 3,000 vouchers for individuals in the last two years, only 728 people have moved into housing, according to D.C.’s Department of Human Services.

Homelessness may have led directly to deaths caused by hypothermia or targeted violence. In other cases, living outside or in temporary shelter could have exacerbated individuals’ existing health issues, advocates said.

“Most of the deaths are preventable, and would not have happened in a safe, decent, affordable home,” said Donald Whitehead, executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless. “It is in their memory, and in the memories of many of the thousands of others across the country, that we must use this as a reason to change the conditions of this country — and we must do it today. We must bring America home now.”

Honoring those who died unhoused

At the vigil, representatives from the National Coalition for the Homeless read the initials of 70 people the community submitted to be remembered. At last year’s event, 66 names were read.

“If any other group this large died, they would shut the city down,” said Micheal Coleman, a member of PFFC and the D.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness.

This is the current list of people who died without housing in DC as well as the list of people who died after moving into housing. May their memories be for a revolution. Join @WashingtonPffc tonight @LutherPlace to honor their lives. pic.twitter.com/P5u7meEa8W

— Jesse Rabinowitz ????????@[email protected] (@jesserbnwtz) December 20, 2022

While D.C.’s medical examiner has identified 77 people who died without homes in 2022, it’s almost certain the real number is higher given that the preliminary count only includes deaths through September. When PFFC held its first vigil in 2013, it read 26 names, but this is also believed to be an undercount given that the city had fewer ways at the time to track people in the homeless services system. The number of reported deaths rose every year after that, reaching 180 in 2020, until it dropped to 124 last year.

Across the country, the National Coalition for the Homeless estimates that 13,000 people die each year without housing.

The oldest person experiencing homelessness to die last year in D.C. was 79, just two years older than the U.S. life expectancy of 77. The average age of those who died was 54. Among those remembered at the vigil, 84% were Black, according to Miriam’s Kitchen advocacy director Jesse Rabinowitz, who helped compile the names.

Most of the deaths were ruled “accidental” by the medical examiner, including 45 due to intoxication and three from hypothermia. For people who died by “natural” causes, such as cardiovascular disease, homelessness is a contributing factor, advocates argue. People without a permanent home are less likely to have access to health care, routinely exposed to extreme weather, and vulnerable to violence. Four people without a home were murdered in 2022, including a man fatally shot at Thomas Circle in May.

PFFC and other outreach groups strive to make conditions less dangerous by distributing sleeping bags, blankets and hand warmers; providing food and water; and conducting wellness checks. But the only way to really prevent people from dying unhoused, Anderson said, is to provide housing. PFFC’s end goal is for the city to implement a universal right to housing.

Over half who died were matched to a voucher

At least 60% of people who died without a home in the last year were matched to a Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) voucher, according to Rabinowitz. To qualify for a PSH voucher, individuals must have a chronic disabling condition that could be made worse by living outside or in a temporary shelter.

“We recognized that they were sick — sick enough to need a Permanent Supportive Housing voucher,” Rabinowitz said of the city’s culpability. “But we could not move with the urgency needed to end their homelessness.”

Over the last two years, D.C. funded enough PSH vouchers to end homelessness for all chronically homeless individuals, advocates say. But only 728 people have moved in with those vouchers so far due to a variety of factors, including a lengthy application process and insufficient staffing. About 2,000 people who sleep outside or in shelters have a voucher waiting for them, as did 42 people who died in 2022.

On the morning of Dec. 21, Rabinowitz led a discussion with PFFC members about what they’d like to see in the city’s next budget. Almost all the answers called for a faster voucher system.

“That the process of housing people will not take two, three, four years,” said Queenie Featherstone, a Street Sense Media vendor.

People eligible for a voucher have to go through a complicated process before they move into housing, including being matched to a case manager, officially applying with the D.C. Housing Authority and finding an apartment. Currently, nonprofits that administer vouchers say they’re struggling to hire enough case managers, leaving hundreds of potential clients stuck at the first step in the process. Encampment residents are waiting months to meet with a case manager even after they’ve been told they’re eligible for a voucher. If residents have to move during that time, outreach providers may lose touch with them.

Proposed solutions

Once voucher applicants have a case manager, the process can still take up to nine months as people contend with bureaucracy, housing discrimination and a lack of affordable units in D.C.

PFFC members asked for the city to make the process easier by reducing application requirements and incentivizing landlords to accept vouchers. They also suggested giving voucher holders the choice of taking on more responsibility in the application process as a way to unburden case managers. Those who have a PSH voucher but no longer need the intensive services that come with it could also be shifted to another type of voucher, freeing up their case managers. Most people in PSH could qualify for these other vouchers, but there’s currently a decades-long waiting list that federal and local funds cannot cover.

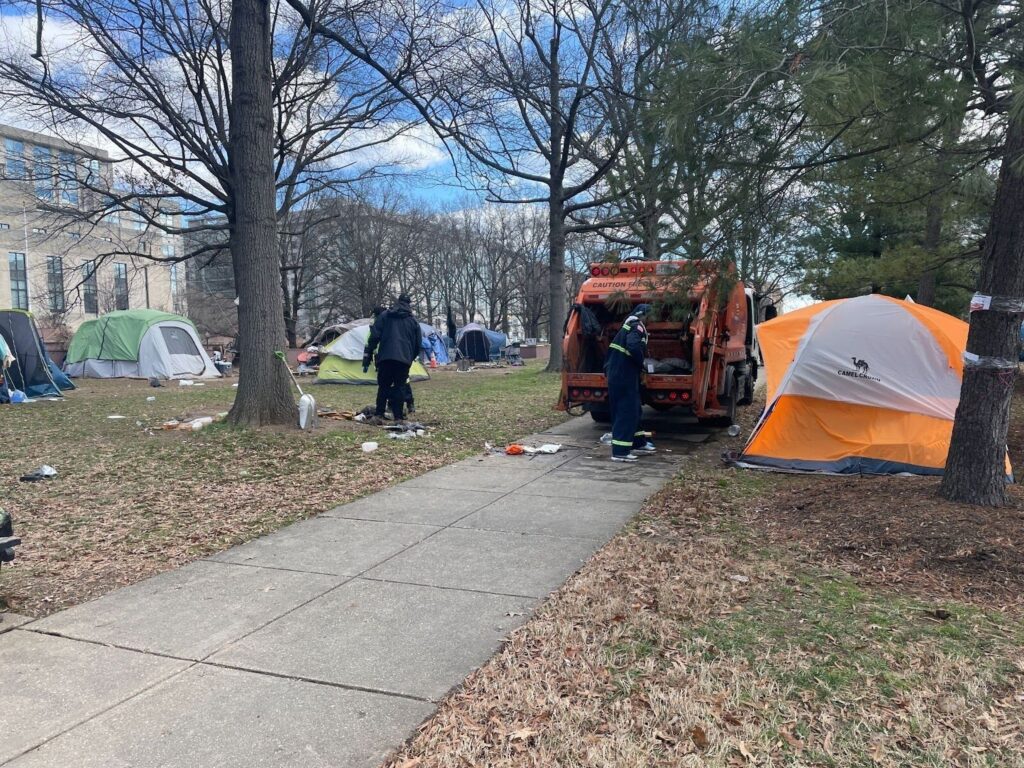

Many people live outside in encampments while waiting for housing vouchers. Several outreach groups and people with lived experience have asked D.C. and the federal government not to remove encampments, arguing that closures can lead to poor health as people may lose medicine and protection from inclement weather. In mid-December, the National Park Service closed an encampment at Scott Circle during a hypothermia alert. Officials said health and safety concerns, common justifications for clearings, necessitated immediate action.

Last month’s vigil also honored 172 people who were once homeless who died over the past year, some soon after they moved into housing. Anderson said while housing can mitigate health concerns, many people struggle with the adjustment, or don’t have the support needed to get proper health care. He knew one woman who entered a diabetic coma after being housed and abandoned by her case manager.

“Most people who move in are bringing a lot of issues with them,” Anderson said.

Nearly every person who spoke at the vigil ended their speech with the hope that those who died in 2022 would be the last.

“They were fathers, they were sons, they were daughters, and they were mothers. They were schoolteachers, they were firemen, and they were doctors,” Whitehead said. “They were a failure of the richest country in the world to provide for those who cannot provide for themselves.”

Anyone wishing to donate to PFFC can do so via the organization’s website, pffcdc.org.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Annemarie Cuccia covers D.C. government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. This joint position was made possible by The Nash Foundation and individual contributors.