A massive fire at a homeless encampment in the NoMa neighborhood consumed three tents on April 8. No one was injured, according to The Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department.

The fire broke out shortly before 1:30 p.m. beneath the train tracks in the 200 block of L Street Northeast. The billowing black smoke could be seen from Shaw, a Twitter user wrote. It was all but extinguished in less than 15 minutes.

“Our investigators were not able to determine a specific cause, so the fire has been listed as undetermined,” the department’s public information officer said. Street Sense Media has filed a public records request for the FEMS incident report.

Update homeless encampment Fire 100 block L St NE. #DCsBravest extinguished fire. Searched the area and found no victims or injured parties. No damage to overhead bridge structure. Investigators on scene seeking cause. pic.twitter.com/hwEZZ9RRX7

— DC Fire and EMS #StayHomeDC (@dcfireems) April 8, 2020

A young woman who has been homeless in and around the D.C. area for the past 6 months said she suspects the fire was set intentionally. Independently interviewed encampment residents gave competing accounts of who was responsible, but all agreed the fire was purposeful and malicious.

There is no police report associated with the fire, according to the MPD press office. Security cameras were installed in the underpass a year ago along with the “Lightweave” LED art installation, but Street Sense could not confirm what the footage revealed based on the agencies’ responses.

Another person staying in the L Street underpass worried the fire their neighbors fell victim to could cause negative attention toward the homeless community, specifically because three propane canisters exploded in the blaze. The FEMS investigation is ongoing but it appears the canisters were not determined to be the cause, according to Ami Angell, founder of the nonprofit The h3 Project. Angell arrived at the scene as the fire was being put out. She has been providing increased outreach to distribute supplies there every day since the coronavirus outbreak escalated in mid-March.

Everything inside the tents, where four people had lived, was destroyed.

“I lost all my clothes,” said Mike, who didn’t want to give his last name. “So, I’m walking around with no clothes, but I’ll come up out of it.”

Each person knew someone else homeless in the city whose tent they could move into temporarily, according to Angell.

One of the ripple effects of the fire in the time of the novel coronavirus is a shortage of medical supplies and access to medical resources. One of the people who lost their home also lost critical medication and is struggling to obtain more. “Emergency reinstatement is a nightmare right now,” Angell said.

On the micro level, she recommended people interested in helping this community contact outreach workers to target that support. Most of what remains are very specific needs or desires, according to Angell, such as a certain size pair of shoes or a favorite book. “We’ve solved for clothes,” she said. Outreach workers in the city cannot provide people tents. In addition to The H3 Project, teams from the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services, HIPS, and Pathways to Housing D.C. regularly work with the homeless community in NoMa.

Mike Dohmann, 26, a tenant at the nearby Avalon apartments, collected $360 from residents in his building and donated it to the victims of the fire. He said the average contribution was roughly $20.

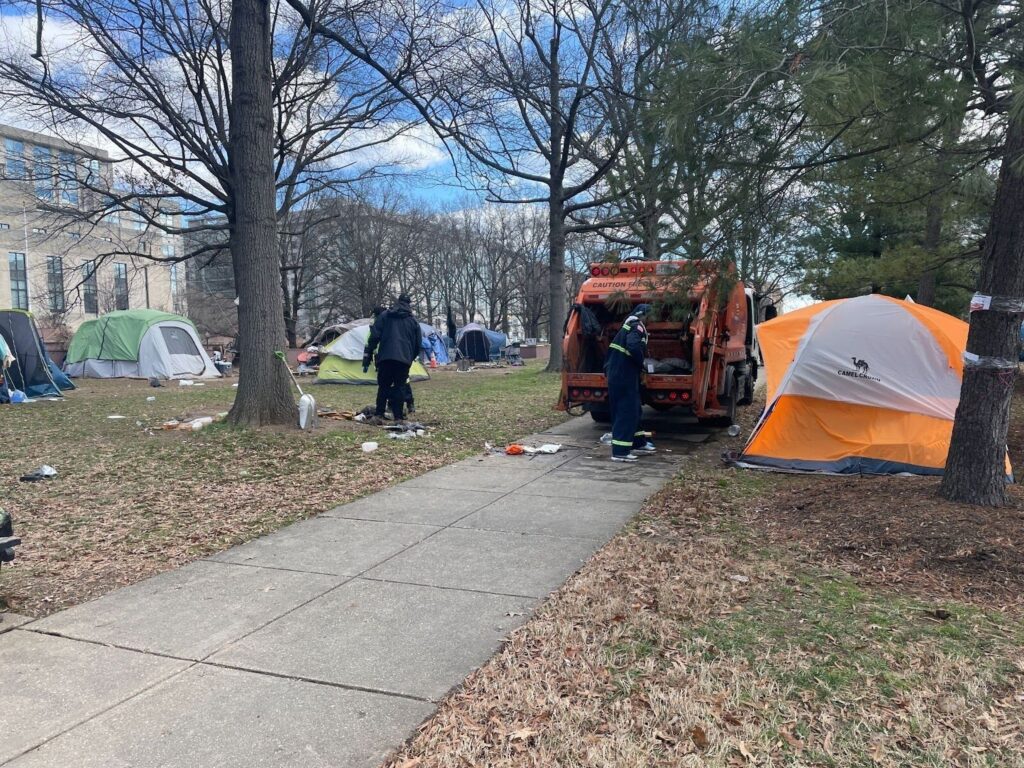

On the macro level, Angell hopes more resources can be provided to encampment residents to keep them safe until they can be connected with housing. She praised the handwashing stations and portable restrooms that had been installed on both M Street and L Street in response to the pandemic. She suggested that if propane canisters became a concern, the city could establish a communal cooking area where those materials could be stored away from people’s tents. In a report documenting the growth of tent cities in the U.S., the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty said providing access to sanitation facilities and water, regular trash removal, and safe cooking facilities improves the health and safety of all.

Advocates have been lobbying for restrooms and more trash receptacles to be installed near the NoMa underpasses and serviced by the city long before COVID-19 arrived in the District. Officials have resisted adding anything that would make the camp communities more permanent.

The temporary sanitation stations align with prevention measures recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on March 22: “Unless individual housing units are available, do not clear encampments during community spread of COVID-19. … If toilets or handwashing facilities are not available nearby, provide access to portable latrines with handwashing facilities for encampments of more than 10 people.”

Correction (04.17.2020)

This article has been updated to include Ami Angell’s correct title and to clarify that no determinations have been made in the investigation.