Imagine you’re months behind on rent. You receive a letter from your landlord that says you need to make good on all your past due rent payments or leave. What do you do?

Assuming you’re in D.C., all is not lost. As a tenant, you have a range of protections and resources available to help you navigate what comes next.

Last week, the D.C. Council passed emergency legislation aimed at avoiding or delaying evictions, which is still due for a signature from the mayor before becoming law. The legislation comes as the public health emergency is coming to an end on July 25. Since the eviction moratorium is tied to the public health emergency, the council sought to address how evictions will work.

In general, the bill, if signed, requires landlords to first apply for rental assistance under STAY D.C., the city’s COVID-19 emergency rental assistance program, before evicting anyone for nonpayment of rent. But there are several large caveats to this policy.

In the case of tenants who have applied for STAY D.C., landlords will not be able to file for eviction for non-payment of rent unless their application has been denied or the tenant owes more than two months or $600 in back rent (whichever is greater).

That second caveat is unlikely to block landlords from pursuing evictions in most cases. According to a Georgetown University study, only 12% of tenants who owed back rent in 2018 owed $600 or less — most people owed about $1,207. When a tenant does owe more than the legislation stipulates, their landlords are expected to provide the option of a payment plan before filing for eviction.

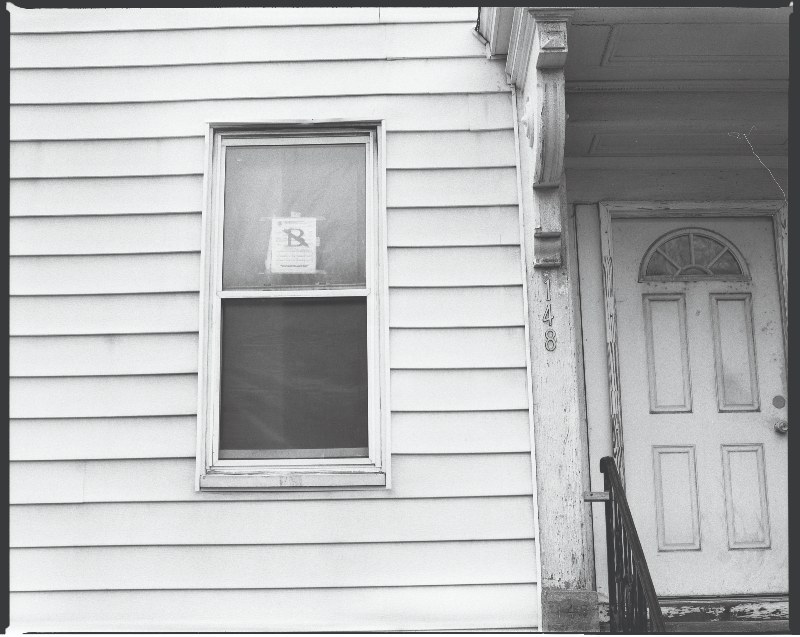

The new law also sets out requirements for the 60-day notices landlords send to tenants to inform them of their intent to file for evictions. In addition to listing the total past due amount, they must include plain, non-threatening language that outlines what rights tenants have, the steps they can take to avoid eviction, and contact numbers for various legal resources.

But some tenant advocates believe the notices themselves — however cautiously they’re written — may be enough to cause people to panic.

Aaron Pope, the senior communications specialist for the Legal Aid Society of D.C., bases his concern on personal experience. For him, all it took was a letter from his landlord saying he had two weeks to move.

In 1999, while Pope was studying at Howard University, he rented a basement apartment in a town house near Rock Creek Park when one day he noticed rats scurrying in and out of the walls. Pope had attempted to get his landlord to resolve the issue — which he blamed on a large hole in the wall left by his landlord’s shoddy attempt to install a radiator.

Ultimately, however, Pope’s landlord did not fix the problem and the rats soon took over the apartment, darting in and out of his kitchen, tearing through bags of flour and sugar and scattering the powdered contents all over the counters and the floor.

It was then that Pope, anxious and scared with no place to go, received a letter titled “two weeks to vacate” from his landlord.

“I was 20 years old, maybe 21. It was my first time ever not living with my parents or living in a dorm, I knew nothing about renting an apartment, I knew nothing about the process. So when I see this letter, I’m scared,” Pope said.

He ended up complying with his landlord’s request to vacate, forgoing his security deposit and moving back home with his parents in Central Virginia. All the while he feared, mistakenly, that his credit could be damaged.

In D.C., tenants are not required to vacate their homes without a court order, something Pope didn’t quite understand at the time.

“A lot of times people don’t understand the law,” Pope explained.

Even after D.C. enacted an eviction moratorium in March 2020, some landlords continued to issue notices to tenants ordering them to vacate their homes, banking on their misunderstanding of the law. In response, the council adopted emergency legislation barring landlords from this practice. The moratorium on filings was later challenged by landlords in court, although the District’s law was ultimately upheld by the D.C. Court of Appeals.

Even with the Council’s passage of stronger tenant protections as the eviction ban comes to an end, Pope said he is still worried that vulnerable tenants might react like he did — acting without the knowledge of what legal resources are available for them.

Speaking recently to a group of philanthropists and community organizers about the need to heighten funding and support for civil legal aid services, Kirra Jarratt of the D.C. Bar Foundation highlighted one of the common misconceptions tenants have about the law.

“You’re not guaranteed a right to counsel in civil matters — it’s not like what you see on TV,” Jarratt said.

But many tenants who go to court do not understand this.

In fact, nearly 90% of tenants arrive in court in D.C. without legal representation while 95% of landlords show up with their own lawyer, according to a 2017 study conducted by the D.C. Access to Justice Commission. The study, Pope and Jarratt say, highlights just how little tenants know about their legal rights.

Lori Leibowitz, the managing attorney for D.C.-based nonprofit Neighborhood Legal Services, said tenants often show up to court under mistaken assumptions.

“[Tenants] sometimes think that the landlord’s attorney is their attorney. … [But] the landlord’s attorney is there to represent the landlord and the landlord’s interests,” Leibowitz said.

Councilmembers Kenyan McDuffie, Anita Bonds, and Elissa Silverman co-introduced a measure in 2016 (along with other members who are no longer on the council) that would have guaranteed representation in civil matters. The bill was co-sponsored by Chairman Phil Mendelson and Councilmembers Mary Cheh, Charles Allen, Brianne Nadeau, and Robert White. The bill was also re-introduced in 2017 but did not progress.

Now, however, the council is allocating $11.8 million in its fiscal year 2022 budget to support the Access to Justice Initiative. The initiative provides civil legal representation to potentially thousands of low- and moderate-income District residents, according to budget documents and a press release from Mendelson.

I believe this budget proposal can be transformative for District residents. My goal was to increase equity in education, jobs and access to justice. We also focused on funding programs to improve the quality of life for DC residents

My full statement: https://t.co/5zFjpMlRXx pic.twitter.com/LWgPzFtpMc

— Phil Mendelson (@ChmnMendelson) July 19, 2021

But it’s not just the tenants in court who may operate under false expectations.

“The concern we always, always have is people self-evicting,” Leibowitz said. “It’s tenants saying, ‘Well, I’m behind. I can’t pay my rent’ or ‘This STAY D.C. application is too hard’ or ‘My landlord doesn’t want me here, so I’m just going to pack up and move.’”

People who find themselves in this situation, Leibowitz said, generally do not have a safe place to go.

In Leibowitz’s experience, immigrants and others who have limited English proficiency are particularly vulnerable, often fearing the consequences of not caving into the demands of their landlords.

During the pandemic, a surge of “invisible evictions” targeting immigrants, who were illegally threatened or coerced by their landlords to move out.

Many legal aid advocates expect the resumption of eviction filings will mostly affect the city’s Black and Latino residents, who are more likely to rent and generally have higher rates of rent burden. According to a May report by the D.C. Council Office on Racial Equity, more than half of the city’s Black and Latino residents spend more than 30% of their income on rent, compared to about a third of white households.

Then there are others who feel disappointed or guilty of their own inability to pay rent — unaware of the financial resources available to them or where to even seek legal help.

Leibowitz said many renters are still not aware of STAY D.C. and may find the latest legislation confusing. At a D.C. Council budget work session on July 8, Ward 4’s Janeese Lewis George reported that STAY D.C. had a backlog of over 16,000 applications, with another 20,000 unfinished applications in draft form.

Advocates say there’s an obvious reason so many tenants haven’t completed the process.

“Those applications take over an hour when I fill them out,” Leibowitz said. And that is after applicants have gathered all their documents together, she added.

The city’s rent relief program for people affected by the pandemic has been mired with a range of technical and administrative challenges since its launch in April. The difficulty of navigating the STAY D.C. portal itself may contribute to tenants opting to abandon the platform and self-evict, without thinking through all their options. During the budget work session, Lewis George warned of a potential deluge of eviction filings in September, potentially before tenants who applied for rental assistance will have even received the aid they needed.

Even without any new filings, more than 300 evictions are still looming — on hold since May 2021 after landlords obtained writs from the court. And there are probably several hundred more now, according to Beth Mellen, supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society of D.C.

From March 11, 2020, through the end of the year, 1,854 eviction cases were filed in the Landlord and Tenant Branch of the D.C. Superior Court. Two-thirds of the cases were filed in March (before the public health moratorium), 388 in April and 78 in May, slowing to a trickle for the subsequent months, per a case ruling filed by the D.C. Superior Court in December.

Leibowitz recommends that people who need help or are confused by the eviction process contact the Landlord Tenant Legal Assistance Network, a collaboration of six legal nonprofits, at (202) 780-2575. Support is available in English, Spanish, and other languages.

Additionally, the Legal Aid Society of D.C. created a tenant toolkit that outlines the process for evictions, and highlights the array of resources available to tenants renting in D.C. The toolkit also offers recommendations for how to communicate with landlords who are not responding to maintenance concerns.

So, what do you do if you receive a notice from your landlord asking you to pay up on your back rent or move? The consensus from legal advocates across D.C. is to turn to an attorney and ask for help.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Will Schick covers DC government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. Year one of this joint position was made possible by the Poynter-Koch Media and Journalism Fellowship, The Nash Foundation, and individual contributors.