Since the 1990s, an instrumental part of decreasing teen pregnancies in Washington, D.C. has been the New Heights program. However, in recent years, the program has faced uncertainty due to proposed budget cuts and reorganization. Its remaining staff have shown resilience, increasing the number of schools and members each person supports.

New Heights is available in 13 of the District’s 21 high schools, focused on those that primarily serve low-income teenagers. “We also support middle school students as needed,” wrote Program Manager Adia Burns in an email to Street Sense Media.

The goals of the program are to prevent repeat pregnancies and increase graduation rates and improve school attendance for parenting high school students, male or female. Once the child is born, students are able to receive resources which include daycare, government financial assistance, and career planning. The program’s approximately $1 million annual budget allows all services to be free for students: approximately 130 parenting teens thus far in 2021, according to DCPS.

Three decades ago, there was a concerning rise in teen pregnancies across the nation. Adolescent pregnancies reached their peak in 1991 with 175 pregnancies per 1,000 18-19-year-olds. According to a 2007 study, “teen pregnancy and parenting is the leading cause of high school girls dropping out of school, representing 30 to 40% of all female dropouts.” The pregnancy rate for teenagers in D.C. has fallen over 85% since then, partially due to programs like New Heights. The program started in the 1990s, as a partnership with the D.C. Department of Human Services, serving only two schools and funded by DHS’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds. With the help of a 2010 federal grant, it dramatically expanded to all of the District’s large comprehensive high schools in time for the 2011-2012 school year.

LaShawn Jones, a New Heights staff member since 2011, said that along with aiding students with employment and career counseling, the program’s goal is to ensure graduating seniors have a plan for after high school.

“If we can help support them, whether that’s doing resume writing, or trying to help them do an application or even prep for an interview, just the basic steps, we help to try to guide that process,” Jones said.

A core part of New Heights that differentiates it from other programs is the resources provided for the newborn or infant. These resources include but are not limited to: diapers, wipes, toys, and learning books.

Maia Schafer, a program coordinator at Anacostia High School, said, “First and foremost, we offer our students tangible items that they need in an effort to relieve stress while they’re trying to finish school … anything you can think of that the baby may need.”

Many young parents need these supplies for their children. For many of these teenagers, New Heights may be the only accessible place that can provide these resources.

Our New Heights Program helps keep expectant and parenting students on track. In DCPS, all means all! https://t.co/LD92dd0Q72

— Chancellor Ferebee (@DCPSChancellor) June 21, 2017

Nataly, an alumnus of the New Heights program, said she is thankful for the support she received from the coordinators while pregnant and afterward.

“During that pregnancy, I was going through a hard process, because I thought that being pregnant was gonna get in between my school, like getting my education. And I thought of dropping out of high school. But then, with the support of Ms. LaShawn and my parents — that kept me inspired to continue high school.”

The interactions between New Heights program coordinators and the participants are analogous to a parent-child relationship. Jones occasionally refers to Nataly as her child, pushing the idea that she cares for all New Heights participants as family — and wants the best for them.

Seven years after receiving the federal grant that allowed New Heights to expand throughout D.C. high schools, an independent evaluation commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that the program resulted in fewer unexcused absences, more course credits obtained, and higher graduation rates for parenting teens. “The New Heights approach is filling a pressing need in Washington, D.C., in helping parenting females remain in school and make progress toward completion, which in turn can lead to improved long-term outcomes for both mother and child,” the report said.

[su_youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rEHdHZsmbzU” width=”800″ rel=”no” modestbranding=”yes” theme=”light” playsinline=”yes” title=”US HHS video on New Heights”]

Learning to pivot during the pandemic

Jones, along with her New Heights colleagues, had to learn new ways to continue providing the necessary support for participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. This meant using FaceTime, Zoom, Microsoft Teams — whatever platform that was available to keep in touch with the young parents.

Jones encourages the young people she supports at Cardozo Education Campus, Eastern High School, and Dunbar High School to reach out to her and keep in constant communication.

“Call me, let me know what’s going on so I can know how to support you in this process, because this is not our normal — but we need to still function, especially because now you’re supposed to graduate,” Jones described her message for her students. “We really need you to attend classes, I need you to log in, I need you to turn in work so we can make sure that you’re still on task.”

[Read more: Community organizations face difficulties providing vulnerable children with wellness support]

One method the New Heights program implemented across D.C. Public Schools is a newsletter.

“We send out every two weeks to our students,” Jones said. “We’re celebrating them or providing them with resources and information. There are articles or recipes, and what to do with your child while you’re at home. Just really understanding what they were going through.”

As the pandemic stretched on, operations were shaky. The program had to keep finding innovative ways to ensure participants received all the necessary resources and supplies.

“That’s when we developed the first drop off,” Jones said “We will either find out which addresses or time [the parent]’s gonna be home, and then try to do those deliveries of supplemental supplies that you were regularly getting in person. Like diapers, wipes, sometimes formula – if we can get our hands on it.”

The importance of community organizations

During the pandemic, the New Heights program has been unable to be the sole provider of certain resources. They rely on partners like the Greater D.C. Diaper Bank and many more to provide for the community.

Partners are critical even in good times. “The idea was to place a coordinator in the schools, rather than a program. The person was going to be the link to already existing programs,” said Megan Moore, a former New Heights coordinator for a D.C. public charter school, in a 2016 documentary about the program.

[su_vimeo url=”https://vimeo.com/88305305″ width=”800″]

Similar to the New Heights program and the Greater D.C. Diaper Bank, there are more organizations in the region doing work for young people around pregnancy prevention and safe sex. Organizations like Young Women’s Project and Sasha Bruce are not formal partners with the New Heights program but they, too, have a profound impact on youth in need.

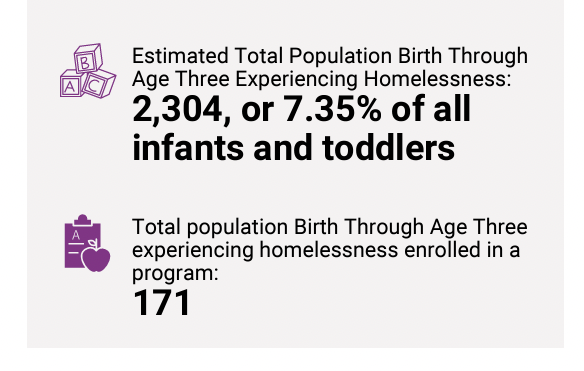

Olaiya’s Cradle, a program within the youth homelessness nonprofit Sasha Bruce, aims to support young mothers without homes, providing them with counseling and infant health care. “Our outcomes are to reduce risky behaviors, including teen pregnancy, course failures, suspension rates,” said Courtney Gibbs, a teen outreach program manager.

[Read more: Pregnant women with no children are shut out of family shelter spaces until their third trimester]

Comparable to Olaiya’s Cradle, the Young Women’s Project centers teen women and youth in the foster care system by equipping them with comprehensive sex education and adequate reproductive health care, as well as encouraging the teens to become peer educators in their community.

“What that program does is [provide] quick tools for high school students in their communities to actually distribute sexual health resources and become resources for when students have questions about sexual health,” said Chika Onwuvuche, a senior program manager for Young Women’s Project. “So that can be anything from pregnancy to STDs to the menstrual cycle to sexual harassment. And so they are really equipped with trying to decrease the teen pregnancy rate.”

Akin to the New Heights program, the Young Women’s Project and Olaiya’s Cradle work across the community to ensure under-resourced young people have access to pregnancy prevention, health care, and therapy. By tapping into organizations across the District for resources, these programs are able to provide the best services for low-income and marginalized youth.

Lack of access and education for poor youth

While nationwide teen pregnancy rates have decreased over the past three decades, the statistics for teenagers of color are disproportionately higher than for white teenage girls. According to the Centers for Disease Control, in 2017, rates were two times higher for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black teens compared to non-Hispanic white teenagers.

Research has found that socioeconomic issues like low education levels, racial segregation, and poverty contribute to higher levels of teen pregnancy. These problems are widely spread across D.C.’s predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods.

This year, the median income for Black residents in Washington D.C. is $46,301 in comparison to $143,150 for white residents.

Disparate levels of poverty for the Black D.C. community are compounded by racial segregation across the District. In 2021, D.C. Health Matters, a project of the National Institutes for Health, reported that the majority of Black people live in wards 5, 7, and 8. Black residents are being pushed east of the Anacostia River into areas that are food deserts and have low-rated public schools.

[Read more: With a return to limited in-person learning, some DC families see hope while others remain wary]

Gibbs, who works predominantly in wards 7 and 8, said, “They may not be able to articulate what exactly is going on, but they know that they don’t have the same access as other people across the city.”

According to the D.C. Policy Center, more than half of the food deserts in Washington D.C. are located in Ward 8. A food desert is defined as an area with limited access to a supermarket, high poverty rates, and low car access.

Along with a high number of food deserts in predominantly Black areas, Ward 7 and 8 hold half of the District’s lowest-performing schools. In 2017, according to a star rating system, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education found that five of the bottom schools in D.C. were located in Ward 8.

While more recent information hasn’t been published by the Office of the State Superintendent due to COVID-19, School Digger compiled data from a variety of education bureaus for the 2018-2019 school year. According to the site, the top elementary schools are in the Northwest region of D.C. — which holds a large portion of the wealthiest residents in the District.

Combined, these factors can result in higher levels of teen pregnancy. Without adequate resources, education, and income, Black and brown teenagers aren’t equipped to know about preventative pregnancy measures or resources to take care of their child.

Based on her work at the New Heights program, Shafer said, “If you have money, you can afford an abortion. If you are educated, then nine times out of ten, you can put your daughter on birth control.”

The battle to keep New Heights funded

Despite its success, New Heights seems to have only recently overcome a multi-year battle to remain funded.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser included a $420,000 cut to the program in her fiscal year 2019 budget proposal. At the time, Amanda Alexander, interim director of DCPS, said some of the responsibilities of New Heights coordinators would shift to existing DCPS school-based social workers and counselors.

The move prompted a backlash from staff as well as the students they served, many of whom testified to the D.C. Council about the positive effects they felt from New Heights.

“A budget cut a few years ago resulted in losing three staff and supply money,” testified Beth Perry, during a D.C. Council hearing on the budget at the time. “We adjusted without compromising services by doubling up schools and sharing supplies. Last week, the entire program was cut. I am not sure why. I can only think, perhaps, people do not know what we do.”

Hard to accept @dcpublicschools budget. New Heights program for expectant & parenting teens is once again sustaining cuts. Started w 15 coordinators, was cut to 9, & now 2 more being cut in FY20. The program has been studied and yields results: https://t.co/UaSPM8Zd3A #AllDCKids https://t.co/GbXJWwfNy8

— Sandra Moscoso (@sandramoscoso) March 29, 2019

At-large Councilmember Robert White eventually succeeded in finding enough funding to keep the program afloat.

However, the next year, the New Heights budget was completely eliminated in Bowser’s fiscal year 2020 proposal, again triggering pushback from the community it serves.

“First, I’ll start off by saying that New Heights isn’t only a program, but it’s a home,” said Inesha Andrews, then a student at Anacostia High School, in a D.C. Council hearing.

“Throughout the program, we just learned so much about being young adults and how it is to be in the real world.”

Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau ultimately intervened and the program received supplemental funding to bring its budget for FY2020 back up to approximately $1 million.

This recurring fight changed in the development of the fiscal year 2021 budget. New Heights transitioned from being jointly funded through DHS and DCPS to being solely funded through DCPS and its budget was increased.

The program will presumably also have stable funding this year. “No DCPS school will experience a reduction in their FY22 budget,” Mayor Bowser declared in a press release last month, thanks to federal recovery funds. “All schools will have an FY22 budget that at least matches FY21 funding levels.” Her fiscal year 2022 proposed budget is expected to be released on May 27.

People touched personally by New Heights continue to champion it as one of the best options for teenage parents in the DCPS system.

Schafer referred to the program as, “the only place in the building that is tailored for [pregnant students.] They’re the most unique group in the building. It’s the most stigmatized group. So, they have got our place where they can come, they don’t feel stigmatized.”

It’s important that teen parents know there is a place that welcomes them since that may not be the case in their home life.

Former At-large Councilmember David Grosso, who chaired the Education Committee during the budget debates over the past three budget cycles, told Street Sense Media, “Just because you’re having a baby doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be welcomed in school, and so I think what they do is really give an opportunity to welcome teen parents into school. Make them feel comfortable and engaged and give them a chance to really excel in school.”

The New Heights program has overcome many challenges in the past year. A core part of the program is face-to-face interaction with young parents and daycare assistance. Program coordinators like Maia Schafer and LaShawn Jones have had to get creative to maintain contact with the participants. Even with this work, there is more to do for the New Heights program and young parents across the District.

As the city moves forward, Grosso said more funding should be dedicated to supporting students who face the most adversity. Childcare-focused partners like New Heights are essential to give students the capacity to focus on learning supports such as tutoring.

“The child is also important to the parent,” Gross said. “So, you don’t want to just remove them from each other, you have to do it in connection with each other.”

Correction (05.24.2021)

The spelling of Program Coordinator Maia Shafer’s last name has been corrected and it has been clarified that Megan Moore, who was quoted from the 2016 documentary, is a former New Heights coordinator. Moore worked for the program through the Student Support Center, which was dissolved in 2015 due to financial constraints.