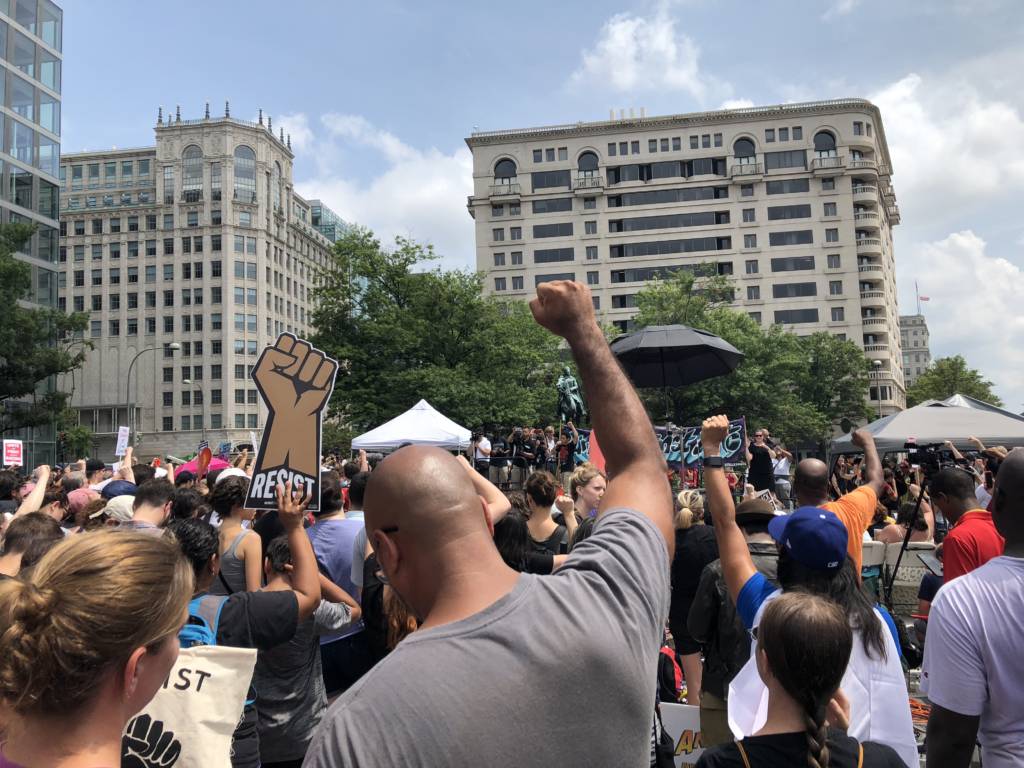

On Aug. 12 — one year to the day of the white supremacy rally that left three dead and multiple injured in Charlottesville — hundreds of counter-protesters marched on Washington in opposition of a second small demonstration.

Fears of a repeat of last year’s violence, which included the death of counter-protester Heather Heyer, weighed heavily on the minds of many. This year, in his submitted public-gathering permit, principle “Unite the Right” rally organizer Jason Kessler said he anticipated anywhere from 100 to 400 participants. But the turnout ultimately consisted of only about 20 people.

The white supremacist group marched to Lafayette Square from the Foggy Bottom Metro station, arriving earlier than anticipated and leaving before its 5:30 demonstration was scheduled to start.

“It could have easily been a larger crowd than what it was,” said Street Sense Media vendor Reginald Black. “And, unfortunately, it was the homeless that were caught up in that unrest.”

Last year, Street Sense Media reported that D.C. government extended low-barrier shelter hours of operation, normally 7 p.m. to 9 a.m., into the daytime on days of extreme weather. The same practice was used to keep shelters open for three consecutive days around President Trump’s inauguration.

A man who had been living in Lafayette Square ahead of the rally, Daniel Kingery, said he expected to be unfazed by it. This would not be the first time his stay at the park, the latest stop of his travels across the country, was affected by public demonstrations. A religious demonstration also forced him to move from his spot not long ago.

Despite this, he said he looks at such events as opportunities to “learn from those who might be an enemy or have been taught to be one.”

Much of Sunday’s spotlight was cast on the motivations and show of force by the counter-protesters: the numerous individuals bearing picket signs and wearing Indiana Jones and Captain America cosplays. While united under a common goal, their reasons for being present were far from collective.

Prior to the rally, at approximately 1 p.m., Lena Muenke and her husband sat underneath a shaded segment of sidewalk at Freedom Plaza with child in hand, supporting the gathering of fellow counter-protesters in front of them. Snuggled in the seat of their baby’s stroller was a sign that read, “You Can’t Spell COLORFUL without FU.”

When asked about her position on First Amendment rights, Muenke teetered between the appeal of unrestricted freedom and taking steps to disarm misinformation. In Germany, where the couple has familial roots, not all free speech is created equal. Some, such as denying the Holocaust, is punishable by law.

“It’s interesting to be in this country where there’s a lot of these rights that people say or use in order to stand up and say things that aren’t acceptable,” Muenke said. “But on the other hand, should people be allowed to say that so there’s a conversation that happens, so you can discuss and think?”

She weighs free speech from her perspective, a White cisgender female. She wonders if she has done enough to acknowledge her privilege and give back to her community. And she contemplates how the privilege that comes with being a White male might affect her son.

“He’s blonde, he’s got all of the textbook privilege, and it’s like, ‘How will I raise him in a way to recognize his privilege and then do something about it?’” she said.

Muenke was reluctant to attend the rally because she wasn’t sure what the atmosphere would be like and whether she and her husband were willing to bring their child when there was risk of violence. In the end, it was their son, to them a glimmer of humanity in a space devoid of it, who motivated them to show up and oppose white supremacy.

A few hours later, counter-protesters poured from Freedom Plaza into Lafayette Square. Another couple, Sam and Ellen, stood underneath yet another shaded area, this time a tree that would later be climbed and used as a vantage point.

Sam and Ellen are somewhere in their 60s and have been doing this much longer than the majority of people present. They’ve attended protested climate change, the Keystone XL Pipeline, the war in Afghanistan, and more “mostly left-wing communist stuff,” Sam said.

“It’s encouraging when we get to thinking about the state of the nation, and how many stupid people there are in this country, that we see younger people coming out to protest on the right side of things,” he said.

Sam is a pessimist, he acknowledges. For him, coming to these events is less about making a difference and more about being useful and doing his part.

“You can’t just stay at home and yell at the TV,” he said.

Sam is uninterested in arguing with people who are set in their ways. He thinks people will, in time, reflect on their own decisions and do the right thing.

“The only people we can try to influence are, unfortunately, people in Congress,” Sam said, “And as far as I can tell, they’re not paying much attention.”

Across the park, Noah Carter and Tori Coan said they were at Charlottesville last year and returned this year to protest “the exploitation of the students and community members who were harmed” at the University of Virginia, Carter said. The next day, they attended the counter-protests to deliver a similar message denouncing white supremacy.

It was difficult to hear Coan over the crowd behind her, yelling “I believe that we will win” over and over again. Her eyes darted to the line of police officers standing behind a barricade, lined through the center of the park, as she talked about how their presence can sometimes make these demonstrations worse.

Carter echoed her sentiments and added that it is difficult to gauge how police presence will affect a situation and what measures they will utilize for crowd control. For him, a protest is successful if no one commits an act of violence and no arrests are made over peaceful activity.

Neither thought this was the best way to engage in discourse with the other side, saying there is no need to discuss the fundamentals of white supremacy.

“The only people who I am here to convince of anything are the predominantly White liberal folks who think that this sort of protest is unacceptable and that we need to be having conversations,” Coan said.

To Coan, “White rights” organizations bare little difference from white supremacists. Kessler has stated that he is not a white nationalist but a civil rights activist petitioning for white people because they “do not have civil rights advocates,” according to the New York Times.

Yet prior to the rally, documents released by the National Park Service indicate Kessler invited multiple white nationalists and white supremacists as keynote speakers, including former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan David Duke.

“White rights organizations say, ‘We are here to support White rights.’ But what’s not included is the second half of that sentence, ‘because other people do not deserve rights,’ ” Coan said.

Contrary to Kingery’s expectations, the “Unite the Right 2” rally and counter-protests did disrupt some members of the District’s homeless community. Shortly after the groups disassembled, residual tension between counter-protests and police transferred onto the streets.

According to Black, the Street Sense Media vendor, this was a result of pent-up frustration from not being able to confront demonstrators, projected on the officers that escorted them. One confrontation between counter-protesters and police occurred in front of the church where Street Sense Media rents office space in Northwest D.C.

A line of police officers stretching onto the sidewalk revved their engines and slowly pushed the crowd to the end of the block, where it dispersed. A few individuals were pepper-sprayed. No tear gas was used, however, it was onsite and ready. Police held the line for about an hour before they moved back.

Dustin Sternbeck, director of the Office of Communications for the Metropolitan Police Department, confirmed that pepper spray was deployed but no injuries were reported.

“As standard protocol, the Metropolitan Police Department is currently reviewing if the deployment of pepper spray was an appropriate use of force,” Sternbeck said.

At the scene, Black said he was attempting to catch a ride when the group had its standoff with police. Ever since MLK Library closed for renovations, the church has served as a replacement stop for the city’s homeless shelter shuttle bus system.

The counter-rally wasn’t something a lot of people experiencing homelessness wanted to participate in, according to Black. Many focused more on getting through their daily routine: making it to the shelter on time and finding out where their next meal was coming from.

“Where this happened is where we usually catch transportation when we are presented with shelter for the night,” Black said. “That particular incident, it caught them up in it without any regard for what they want to do.”

He thinks there is more the District can do to improve its event planning and take into consideration how public demonstrations affect members of the homeless community who do not want to participate.

“This experience showed me that even if you don’t have an opposing view, or if you don’t even have a view at all, we have to now think about these things and make sure that people have safe havens,” Black said.