A year ago, Dr. Mayaalla MuQaddim Abdullah Al Saud was nearly asleep when neon-vested volunteers approached her tent while conducting an annual census of people experiencing homelessness. They asked how long she’d been sleeping outside, whether she had any health problems, and what help she needed from the city.

One year later, Abdullah Al Saud found herself on the other end of the process during the latest Point-in-Time (PIT) Count. Along with a team of volunteers, she helped administer the survey herself, at one point bending under a purple umbrella to speak to a woman sheltering at a bus stop near Union Station.

“It was important to be counted,” Abdullah Al Saud said. “I also felt that if a lot more people see people that were in their position as displaced trying to give back and make their situation better, they would open up more and engage more.”

On Jan. 25, outreach workers, volunteers and employees at shelters and day centers worked together to try to speak to every one of the thousands of people experiencing homelessness in the city. Mandated by the federal government as a condition of grant funding, the PIT Count offers a chance for D.C. officials to see what progress the city has made toward ending homelessness — and what resources people who are still living outside and in shelters need.

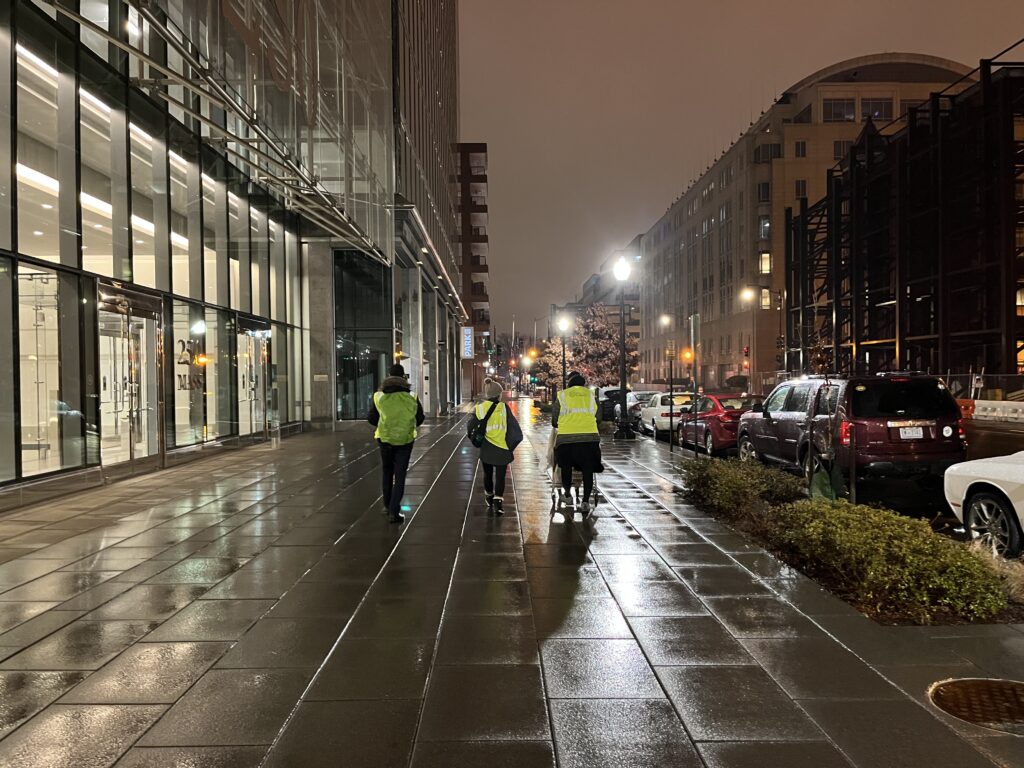

Small teams set out across the District around 8 p.m., each assigned a few square blocks. They walked every street, stopping to ask people if they were sleeping outside and if they’d be willing to answer a 10-minute survey in exchange for a $20 Visa gift card. Volunteers filled out observational surveys for people who appeared to be sleeping outside but declined to answer questions. Staff at low-barrier shelters and transitional housing programs also administered the surveys to include the experiences of people sleeping inside that night.

“The goal really is not just to count people, but to talk to people,” said Christy Respress, the executive director of local nonprofit Pathways to Housing. “We can determine what resources we need, measure our progress over time: Did we actually move the needle with all the hundreds and hundreds of vouchers we have in our system?”

The number of people identified by the PIT Count is supposed to represent the potential demands on the homeless services system on any given night, Respress explained — how many people are sleeping in shelters, in tents and in doorways or bus stops. While there is no single measure used to determine how many people cumulatively experience homelessness in D.C. over the course of a year, the PIT Count is often used to track annual trends in homelessness.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office outlined procedural shortcomings with the survey in a report issued in 2020, finding that the PIT Counts across the country underestimate the number of people experiencing homelessness because of poor methodology and varying standards for data collection. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development is working to evaluate its methodology and develop more training for organizations conducting the PIT Count.

Still, D.C. uses the data to tailor its housing and human services programs, including determining how much space the city funds in emergency shelters, temporary housing and permanent housing programs. Demographic information from the PIT Count can help the city target services — for instance, responses to questions on gender and sexuality can show if there’s a need for additional male, female or queer-friendly shelter beds.

Last year, the PIT Count identified approximately 4,400 people experiencing homelessness, representing a 14% decline from 2021. District officials say the count — notwithstanding its limitations — shows improvement from past years even though many needs remain unfilled.

“We know that’s not everybody,” At-large Councilmember Robert White said to a group of volunteers gathered at the First Congregational United Church of Christ on the night of the count. “We also recognize that that’s the lowest number since 2001, so we’re making progress.”

Problems with the PIT

The PIT Count is widely recognized as understating the actual number of people experiencing homelessness, a point Abdullah Al Saud represents perfectly. Last year, when Abdullah Al Saud lived in a tent, she was considered literally homeless — someone who “lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” — and was visible to volunteers. She was included in the PIT Count.

This year, however, Abdullah Al Saud is staying at a friend’s house. She’s working with case managers to obtain permanent housing. But because she’s sleeping inside, on a friend’s couch, volunteers would have missed her if she hadn’t asked to be surveyed.

While the count is purposefully conducted in January, when the weather makes it dangerous to sleep outside and more people choose to go to a shelter, that danger can also affect the numbers in other ways, some advocates said. If someone can stay at a friend’s or family member’s home only a few times a year, they might use that opportunity when it’s going to be raining all night long, as it was for this year’s PIT Count, said Andy Wassenich, assistant director of outreach at Miriam’s Kitchen.

“A lot of us stay with a friend, find a room somewhere, people rent storage units, but that isn’t fixing the problem,” Abdullah Al Saud said. “We’re still displaced at the end of the day.”

Volunteer teams had to make judgment calls when coming across other people who sat on the tenuous line between being officially considered “homeless” or not — people who appeared to be spending the night outside but refused to take the survey, or who said they planned to sleep at a friend or family member’s house. Even if they were not counted, some of these people may be eligible for a variety of services, including case management, if they spend about one-third of their time on the streets or in shelters, Wassenich said.

PIT Count organizers do what they can to close any gaps and work to improve the methodology and execution every year, Respress said. This year, for instance, staff at day centers and breakfast programs surveyed everyone who came in on Jan. 26, the day after the count, if they hadn’t completed a survey the night before. This year’s final report will note the weather on the night of the PIT Count and how it may have affected the results, Respress said.

PIT as one number among many

When referring to the number of people experiencing homelessness in D.C., public officials often refer to the PIT Count. But PIT isn’t the only data D.C. has on the scope of housing instability — there’s also the total number of people who access the homeless services system throughout the year, measured through the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS).

Compared to the PIT Count, HMIS data routinely captures at least twice as many individuals experiencing homelessness. The widest gap in recent years was in fiscal year 2018, when PIT Count surveyors counted 3,770 people and HMIS counted 12,343. In FY 2021, the last year for which both sets of data are available, the PIT Count reported 3,871 and HMIS reported 8,325.

While HMIS and PIT statistics on families are normally at least somewhat closer, likely due to the fact that a higher proportion of families stay in shelters and are thus sure to be surveyed, this part of the PIT Count is still lower by hundreds. In FY 2021, the PIT Count identified 405 families experiencing homelessness, while HMIS identified 924.

Both sets of data are valuable, Respress said, depending on what the city is trying to measure. The number of shelter beds needed for any given night? Look at the PIT Count. But the number of slots in permanent or temporary housing programs to add each year? HMIS data.

As for the overall scope of the problem in D.C.? “The number of people in HMIS every year, that is a better indication of what homelessness is like,” Wassenich said.

What the PIT Count does best

The PIT Count, however, offers something HMIS data does not — a chance to understand the varying needs of people who are experiencing homelessness. This year’s survey, which volunteers read off their phones to respondents, included 27 base questions about a person’s race, gender, sexuality, age, length of homelessness, physical and mental health, income, and involvement with the foster care or prison system. The electronic form provides each respondent with a tailored list of questions about other household members, past episodes of homelessness, and interactions with other government agencies.

The questions can be very personal, said a man sleeping in McPherson Square who gave his name as Moon. But he was glad to answer them. “It’s good to know how many people are homeless or have mental illness or health problems, and I think the government should help them,” he said.

The answers to these questions can help D.C. measure the inequities that are replicated in housing instability. Black and queer people experience homelessness at disproportionately high rates in the District, and in 2022, people of color comprised 91% of those counted in the PIT but just 54% of the general population.

At last week’s PIT kickoff event, organizers stressed the importance of collecting data on the number of people managing physical or mental illnesses.

“Enormous health inequalities are found amongst people experiencing homelessness,” said Ceymone Dyce, the vice president of homeless operations at Pathways DC. “Our unhoused neighbors struggle to eat nutritious food, get regular preventative care and manage chronic health conditions.”

The PIT Count can help spur some connections to resources, Respress said. While surveyors didn’t provide case management the night of the PIT Count, the questionnaire included space for volunteers to indicate a person was in need of additional services. In the downtown area, Pathways to Housing planned to have case managers follow up later in the week to connect people to housing resources, according to Respress.

“Collecting data should only be the first step,” said Jesse Rabinowitz, senior manager of policy and advocacy at Miriam’s Kitchen. “We really need this data to drive funding, policy, resources and interventions, so next year we’re collecting fewer people than last year.”

When do the results come out?

The results from this year’s count won’t be released until the spring, but Respress said homeless services organizations know that more people are living in tents than last year. Even as the city has funded thousands of vouchers to help people move off the streets, only a fraction of those eligible have moved into housing so far.

Mayor Muriel Bowser, who spoke at the kickoff event, said the PIT numbers will drive policy decisions in the next year. “You know that I’m gonna be there; you know that we’re gonna keep making the investments to live up to our commitment to get all our residents home,” she said.

Moon, the middle-aged man living in McPherson Square park, is hoping he’s one of those residents. He’s experienced homelessness since he was 14 and has lived through years of PIT Counts. The National Park Service has accelerated previous plans to clear the McPherson Square encampment and is now slated to close the park in mid-February. Meanwhile, Moon said no one has helped him apply for a housing voucher.

“These guys are waiting for housing,” he said, gesturing at the dozens of tents around him. “I would like to apply or whatever. Who do I talk to?”

A slightly different version of this article appeared in print.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Annemarie Cuccia covers D.C. government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. This joint position was made possible by The Nash Foundation and individual contributors.