Sitting outside the bright red doors of the Church of the Epiphany, Colleen peered at her tent on the sidewalk. Soon, city workers would order her to remove it in preparation for the day’s encampment engagement. Colleen’s friends were inside the tent, sorting through her belongings. But with the blaring August sun in her good eye, she couldn’t tell what her friends were placing in the trash bag and what they were placing in the “keep” bag. “I want to keep all that,” she called out to them. She hoped they heard her.

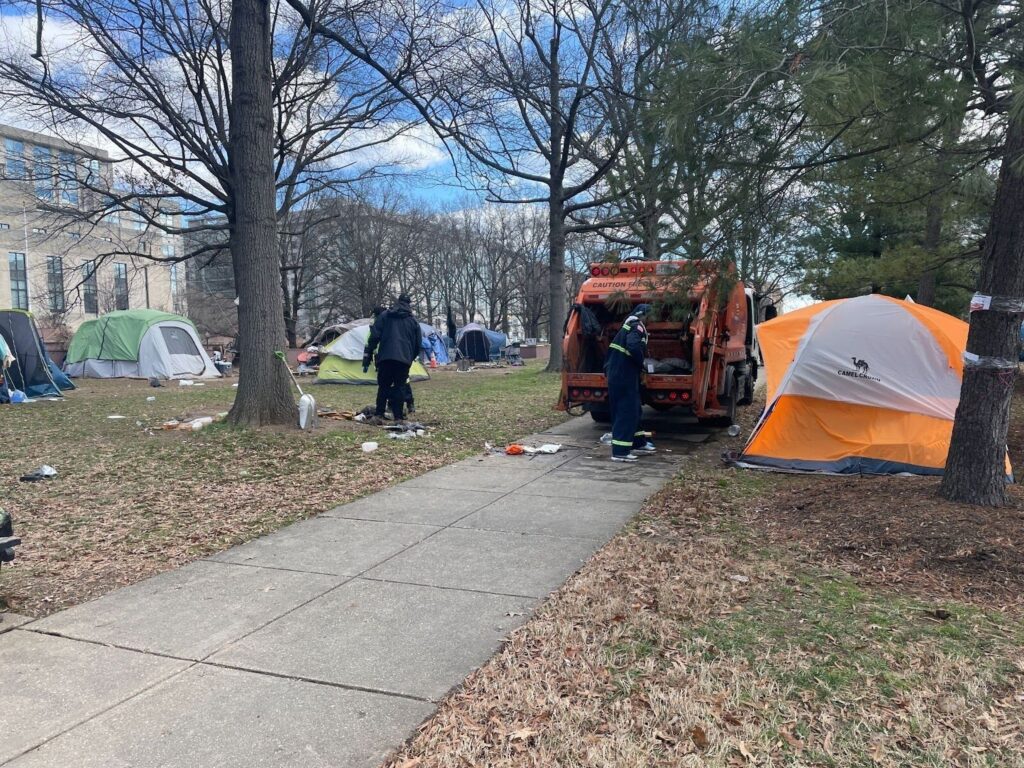

D.C. conducts between 70 and 100 of these encampment engagements every year, discarding trash and removing bulk waste in the areas surrounding tent communities. Encampment residents often have to move during engagements, either temporarily or permanently. City officials say these measures are necessary to protect public health and safety and to help connect unsheltered residents to housing opportunities. But many encampment residents share a different view — they characterize encampment engagements as disruptive events that do little more than traumatize people and rarely, if ever, connect people to housing.

Between June 1 and Aug. 24, city and federal government agencies conducted 17 encampment engagements, including one outside of the Church of the Epiphany, which houses the offices of Street Sense Media. The Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS) and the National Park Service (NPS) fully closed seven of those 17 encampments, permanently displacing over 50 people.

Street Sense spoke to 21 encampment residents who experienced an engagement this summer to better understand the process. Most encampment residents said they generally agree with the city’s stated goals, but feel as though the city’s expectations for engagements are inconsistent with the realities of homelessness. Several people suggested that the city could provide more resources to help unsheltered residents clean encampments and prepare, reducing both the need for and the trauma of engagements.

“It does accomplish something — ruffling our feathers,” said Melvin, a resident at an encampment DMHHS closed this summer. “That’s what it does. Just to keep us on our toes.” (Like most of the people quoted in this story, Melvin agreed to speak on the condition that only his first name be used to protect his privacy.)

The purpose of an encampment engagement

Colleen’s friends carried her “keep” pile — several bulging black garbage bags — into the courtyard behind the church gates. She couldn’t stay where she had slept the night before, but her belongings would be safe on private property just a few feet away. Already tired from the day and worried her heart murmur would act up, Colleen sat on a stone bench beside her longtime neighbor, Carlton. He was sitting on a folding chair, surrounded by everything he owned.

At least 690 people experience unsheltered homelessness in D.C. on any given night, according to D.C.’s Point-in-Time Count, sleeping in doorways, on sidewalks and in public green spaces. They may have no other option if shelters are full, given that D.C. residents only have a legal right to shelter during extremely cold or hot days. Commonly, people who sleep outside say they do so to avoid poor conditions and strict rules at shelters. Encampments allow people experiencing homelessness to form a community and live independently, according to Coco Leonard, who lived in a tent near Mount Vernon Square before NPS cleared the community on Aug. 25.

“We’re still homeless, we’re still broke, but we have what we need,” Leonard said.

DMHHS — which oversees the encampment engagements conducted by the D.C. government — defines an encampment as “a set-up of an abode or place of residence of one or more persons on public property.” They’re found most often in parks and underpasses, and can have just one resident or a few dozen. Some encampments have portable toilets. As the proportion of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness has increased nationwide, some D.C. residents have expressed frustration that the city has not done more to remove tents.

D.C. first adopted rules about how and when the city can clean encampments in 2005, after years of sweeps occurring absent any set schedule and with workers unpredictably throwing out the belongings of people living outside. The city has conducted over 530 encampment engagements since 2015, when DMHHS began posting engagement data online.

DMHHS encourages city residents to report new tent communities via a telephone hotline and email address. “Our protocol for cleaning public spaces is triggered when a site presents a security, health, or safety risk, and/or interferes with community use of such places,” the DMHHS page reads. DMHHS did not provide comment by the time of publication.

The city’s policy has substantial support — a February Washington Post poll showed three-quarters of Washingtonians are in favor of the city clearing large encampments. When housed residents ask the city to remove encampments, they generally cite DMHHS’s first goal: keeping areas clean and safe.

Before DMHHS closed an encampment at New Jersey Avenue and O Street NW Park in the Truxton Circle neighborhood in December 2021, several housed residents wrote to their councilmember alleging instances of theft and drug use in the encampment, according to emails obtained by Street Sense via a Freedom of Information Act request. They also complained about overflowing trash cans and rodents.

NPS — which handles encampment engagements on federally owned parkland under its own guidelines, not the city’s — cites similar concerns. In the two months before NPS closed the Mount Vernon Square encampment, U.S. Park Police reported making 25 arrests at the site and seizing two handguns and $12,000 in narcotics, according to Mike Litterst, NPS communications chief.

Some businesses also push for encampments to be cleaned or closed. A 2021 report from the DowntownDC Business Improvement District expressed concern that the presence of encampments reduces economic activity. The organization’s business plan calls for the removal of encampments when possible, paired with outreach and housing.

Encampment residents speak out

Carlton woke up early the morning of the engagement. Living so close to the White House, he’d seen a lot, but he’d never been through an engagement before. Carlton wasn’t worried, though. He learned a long time ago the only thing he could do was be patient. So he rolled his red canvas wagon behind the church’s gates, unfolded a camping chair and settled in.

Encampment residents generally say concerns about safety and cleanliness are overblown. Many residents clean as much as limited trash cans will allow, Leonard said. And encampment residents often say they’re the ones who are unsafe, facing vitriol from their housed neighbors.

“They treated us homeless people like we were the disease,” said Sean, a resident at an encampment in the Dupont Circle area where DMHHS conducted a cleanup on Aug. 2. “They were treating us like we were second-class, third-class citizens.”

But the biggest critique Street Sense heard from encampment residents is that engagements give little attention to DMHHS’s second stated goal — “enroll residents in safer, healthier living arrangements.”

Some encampment residents have been waiting more than a decade for their name to come up on the District’s voucher and public housing waitlist. Others are stuck in the slow process of getting a Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) voucher; despite funding 2,400 such vouchers this year, D.C. has housed only about 600 people so far.

In 2021, Mayor Muriel Bowser launched the Coordinated Assistance and Resources for Encampments (CARE) Pilot Program to pair permanent encampment closures with housing vouchers for residents. But the city has applied the high-profile program to only four sites thus far, and the city’s other encampment engagements do not come with the same level of outreach and casework to help residents obtain permanent housing via vouchers.

Almost all residents told Street Sense they’d leave their encampment in a heartbeat if they had somewhere safe to live inside. But they all ended the day of the engagement the same way they started it — living on the streets.

The day of an engagement

Through black iron rails, Carlton watched three men sweep the pavement he’d slept on the night before. It didn’t take long; he kept things clean. As Carlton waited for the power-washing truck to arrive, the sun warmed the spot where he sat. He closed his eyes.

The D.C. government’s encampment engagements come in three tiers: trash-only engagements, full cleanups, and closures.

During trash-only engagements, city workers remove bulk waste. Authorities allow residents to keep their tents in place. Trash-only cleanups were common during the first two years of the pandemic, but DMHHS conducted only one this summer.

For full cleanups, the most frequent type, residents have to move all belongings off site by a certain time. DMHHS workers remove anything left behind, and they sweep or rake away dirt and debris. Sometimes, full cleanups are accompanied by a power-wash. Residents can return when the cleaning is finished — normally about three hours later.

Site closures operate like full cleanups, but residents are prohibited from returning.

The city closed two encampments in late July, one on FedEx property on Eckington Place NE and one located near Shaw Middle School at Garnet-Patterson. NPS closed three encampments downtown over the summer, including one at Union Station and another at Mount Vernon Square.

Two weeks before a city-led engagement, D.C. posts a sign notifying encampment residents. According to the city’s protocol, this must be accompanied by outreach from DMHHS, the D.C. Department of Human Services, the D.C. Department of Behavioral Health and contracted service providers. The agencies are supposed to offer temporary and permanent housing placements when available but do not publicly track how many residents are housed, as they do for the CARE pilot.

In the lead-up to engagements this summer, outreach workers from the nonprofit Pathways to Housing enrolled residents in D.C.’s coordinated entry system and made sure they knew about shelter options. Ahead of NPS’s closure of the Union Station encampment in June, Pathways connected some residents to PEP-V, which provides housing accommodations for individuals who are medically vulnerable, and “bridge housing,” which provides temporary shelter for people in the voucher process.

On the day of the engagement, DMHHS arrives about half an hour before the clearing is scheduled to start. Residents are often packing, sometimes with the help of Pathways and similar organizations, mutual aid groups or individual community members. Except in the case of a trash-only cleanup, DMHHS workers are authorized to discard anything still in the area once the engagement officially begins.

When encampment residents are prepared (as Carlton and Colleen were), the cleanup can go smoothly. But across the city, other residents have rushed to pack up their tents at engagements conducted in recent months. If residents are resisting or running behind, DMHHS workers decide whether to dispose of possessions immediately or to give residents extra time. At least four residents Street Sense spoke to this summer lost a significant portion of their belongings during an encampment engagement. On one occasion, Sean said, he watched DMHHS workers unknowingly throw away his mother’s ashes. These experiences can lead to long-lasting trauma, said Aaron Howe, the co-founder of mutual aid group Remora House who has been attending cleanups since 2018.

After a permanent closure, residents often scatter to other established encampments, relying on mutual aid and outreach workers to help them transport their belongings. What they can’t carry, they leave behind. Residents consistently said they are tired and discouraged after clearings. They may be uprooted from their neighborhoods and miles away from the people they care about. And they may feel no closer to housing.

Can DC improve engagements?

After Colleen moved back, her tent wasn’t quite the same. It used to feel permanent, having withstood years of weather. But now it leaned forward in an odd way. The front wall hung a few inches above the ground, fluttering in the wind. Her street looked different, too. Two of her neighbors who’d left before the engagement hadn’t come back yet. She’d been sorting through the trash bags her friends packed her things into. She couldn’t find her can opener.

Supporters of encampment clearings argue engagements leave sites cleaner and safer. Litterst said that criminal activity near Union Station decreased after NPS cleared the encampment.

But encampment residents argue there are other ways to achieve these outcomes — methods that might come with fewer negative second- and third-order effects.

“Everyone has the same goal and desire to be safe and comfortable,” Leonard said. She and other encampment residents want to keep their areas clean, she explained; they’re just up against limited trash can space and a lack of running water. If the city provided more of these amenities, she suggested, engagements might not be necessary. People living outside, including Street Sense vendor Lori Smith, have also called for D.C. to provide more public restrooms, which could also prevent some waste.

If D.C. is going to conduct engagements, the city could pair them with free food and water to help residents through the moving process, suggested Hasan, a former resident of the Mount Vernon Square encampment. At least three residents whose encampments have been closed this summer suggested D.C. could provide transportation to a new location, so residents don’t have to leave behind belongings. D.C. currently provides free transportation only to a storage site.

Carlton, while grateful the church’s proximity gave him a place to wait out the engagement, pointed out that not everyone has that option. He suggested the city put encampment residents in a hotel with their possessions for a day while the city cleans the area. This policy could have helped Hasan — on the day of the clearing, he was headed to dialysis, a four-hour endeavor that leaves him exhausted. A friend was able to look after his belongings, but he didn’t know where he’d be able to rest after the appointment.

Overwhelmingly, residents at encampments closed by DMHHS and NPS said they’d be more willing to move if engagements fulfilled the city’s second goal of connecting residents to housing. Sean and his friend J.P., who also lives at the Dupont Circle encampment, were told in February they’d have housing by July. With rumors swirling that their encampment is at risk of permanent closure, they’re both still waiting. Neither has tremendous confidence: J.P.’s case managers have expressed concern that they might not be able to find him if he moves, and Sean said his case manager lost his birth certificate.

“Just give us the housing you said you was going to give us, and then there won’t be no problem,” J.P. said. “You get people’s hopes up for nothing.”

Carlton reclaimed his 6 feet of sidewalk, setting up his row of camping chairs that greet everyone exiting the Church of the Epiphany. He looked down at the lanyard that hung around his neck. It held a single key. One day, he hopes to add another key — one for an apartment — to go along with it. But for now, he relaxed, glad the engagement was over and hopeful it wouldn’t happen again anytime soon.

This article has been updated to include the correct name for the New Jersey Avenue and O St NW Park.

Atmika Iyer, Hope Davis and Holly Rusch contributed to this report.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Annemarie Cuccia covers D.C. government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. This joint position was made possible by The Nash Foundation and individual contributors.