This year, D.C.’s rate of drug overdose deaths is third highest in the nation, up from seventeenth, according to a panel convened last month by the American Association of Medical Colleges to discuss ways to deal with opioid addiction. The panel discussed opioid abuse, treatment, and fatalities.

The assembled doctors treat patients who wrestle daily with addiction. Those doctors were in agreement: the opioid epidemic, already a serious problem, grew exponentially in the District this year.

“While there are more billionaires, there are also more homeless people,” said panelist Dr. Edwin Chapman, a graduate of Howard University Medical School and a specialist in addiction medicine. “D.C.’s addiction problems have always been to street drugs,” he said.

A recent Washington Post story described how, as opioid use and addiction shifts from heroin to the much stronger fentanyl, long-time users are overdosing and dying in D.C. Washington has become “ground zero” for deaths, according to the story, with more than 279 last year, surpassing the city’s homicide rate. More than 80 percent of those who overdosed were African American.

The Bowser administration has a publicly available 10-year plan that includes cutting opioid use in half by 2020. A summary of the plan, LIVE.LONG.DC, is available online. The AAMC panel moderator said that recent Bowser administration budgets provided $42 million to treat opioid addiction. Treatment for this malady is far cheaper than jail time, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The mayor’s plan also creates a public-private partnership of more than 40 stakeholders. Her administration has given $25,000 in grants to develop curricula on pain management and opioid use.

“Medical schools in the District are doing innovative work … and succeeding in teaching innovative curricula about opioid treatment,” said Ambrose Lane, founder and chair of the Health Alliance Network, an advocacy group for health equity in poor communities.

Audience member Joe Henry spoke up to support funding for health care workers who have demonstrated success. Henry said he benefited from quality help in 2005 and 2006 when he was broke and recently released from jail. “If Dr. Chapman is able to successfully treat addicts who come to his clinic, get him some money,” Henry said.

He added that Howard University Medical School has developed Project ECHO, a national Telehealth Model for rural health care, to extend addiction treatment.

In D.C. there are 300 to 400 medical educators teaching opioid treatment, prevention and recovery to foster inclusive communities, according to Lane. He said the medical education unit of the AAMC has been training the District’s medical educators. “There’s a simplicity we need to have to solve this crisis,” Lane said.

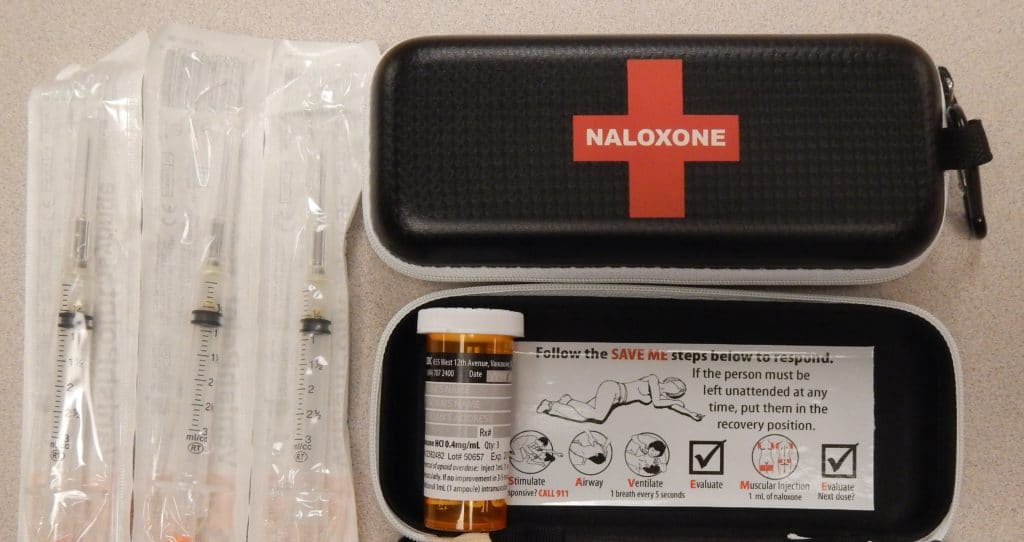

Lane told the assembled group that the substance abuse unit of DC’s Metropolitan Police Department and SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, have launched full investigations of opioid use and are distributing kits to police officers in wards 7 and 8 and downtown D.C.

In the Mayor’s budget, much of the funds to address the opioid crisis come from a State Opioid Response grant from SAMHSA. The SOR grant allots $21 million its first year, plus an additional $21 million its second year. The grant will help increase access to medication-assisted treatment, which combines behavioral therapy and medications to treat opioid-use disorders, reduce unmet treatment needs, and lower opioid overdose-related deaths.

However, according to a report by The Hoya, Georgetown University’s campus newspaper, the D.C. government is facing a federal audit for failing to implement federally funded programs designed to combat the opioid crisis.

D.C. has been on the front lines of expanding access to naloxone, a medication that reverses the effects of opioids, including overdoses. Often referred to by a popular brand name, Narcan, the drug is safe and easy to use, according to a report by The D.C. Policy Center. Local officials have reported cautious optimism; giving it a “degree of success,” though there are also financial concerns.

“It’s too expensive to train police officers to use the kits to help the users, addicts and people on the street where they are,” Lane said during the panel discussion.

The mayor’s office plans to present Mayor Bowser’s LIVE. LONG. DC. to the D.C. Council late this month, after they pass the proposed budget. They anticipate getting to it further into the summer, a Bowser administration spokesperson told Street Sense Media.