On Sunday, February 22, District residents from every ward — many from Ward 8 — crammed into a hot meeting room in the basement of the Anacostia Library and stayed until the loudspeaker announced it was closing time. Everyone was there to discuss the potential displacement of hundreds of African American families living in the Barry Farm public housing project.

Attendees gathered to talk solutions, formulating ground rules such as “be respectful” and “no campaigning.” They also agreed to use Barry Farms, plural, because “nobody from D.C. says Barry Farm.”

The previous weekend, members of Empower DC—a grassroots organization that promotes collective power for low-income communities—and the Barry Farms Tenants and Allies Association spent four hours going door-to-door through Barry Farms to drum up turnout for the Sunday forum. They offered childcare and rides to the Anacostia Library.

“Not everyone understands why we’re fighting. That’s why we’re having the forum,” Schyla Pondexter-Moore, Public Housing Organizer for Empower DC, told Street Sense.

Empower DC and Barry Farms tenants are concerned about displacement now because last October city government finally approved the New Communities Initiative (NCI)’s first stage Planned Unit Development (PUD) for Barry Farms.

Although public housing is federally subsidized for low-income families, the elderly, and persons with disabilities, Barry Farms residents worry that if displaced they will not find housing elsewhere that they can afford.

In 2012, Pondexter-Moore led a successful campaign to preserve public housing at her own Ward 8 residence, Highland Addition. A court case presided over by DC Superior Court Judge Joan Zeldon resulted in a settlement that would keep Highland Addition as public housing for the next 40 years, post ongoing renovations.

“Displacement through redevelopment is part of the reason for the homelessness boom in the District,” Pondexter-Moore said to the packed meeting room.

Despite the PUD approval, DC Housing Authority (DCHA) asserts that there is no funding, and thus no set date to break ground at Barry Farms.

The New Communities Initiative was established in 2005 by former Mayor Anthony Williams to demolish four large public housing projects and replace them with mixed-use communities—residential and commercial—and mixed-income housing: some market rate, some affordable and some public.

Since that time and throughout the development process, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, which houses NCI, and the DCHA have met with residents to gather community input. Federal and District law guarantees public housing residents receive at least three months notice before a required relocation. However, close to a decade of stalled plans and continued meetings has left residents feeling uncomfortable and powerless. Many fear losing their home, not just a housing unit.

***

Tenants worry there will not be enough units to house all of the current residents. At the approval meeting of the first stage PUD, officials agreed they didn’t have enough housing for all the current residents to be relocated, according to Phyllisa Bilal, co-founder of the Barry Farms Study Circle and a panelist at the forum.

“When there is a plan in place, every family will be offered relocation,” Christy Goodman, a spokesperson for DCHA, assured Street Sense. “I can’t promise everyone will receive a voucher, but no one will be turned out on the street.”

Some families have already moved into Sheridan Station and Matthews Memorial.

Several attendees spoke of first-hand experience with displacement from D.C. public housing. Robyn Fields, a resident of Arthur Capper Carrollsburg, was displaced for ten years when D.C. government changed the public housing development into a mixed income community. She went through an extensive background and credit score check before she was allowed back into the community.

“I went to every meeting and stayed informed so I could come back to Arthur Cappers,” Fields said “But everybody ain’t going to do that.”

DCHA plans to work with Barry Farms residents to determine what, if any, return criteria will exist.

“We were one of the first housing authorities in the country to adopt one-for-one. It became federal law after we did it,” Goodman said. “Residents have been a part of the redevelopment process this entire time. We are not going to change that.”

***

A recent report assessing the New Communities Initiative does little to comfort residents, however.

The report was requested by the city and completed last fall by Quadel Consulting and Training LLC; it recommends that New Communities representatives be more clear about their policies, including residents’ “right to return/stay.” According to the report, “While a guiding principle, there is not a guarantee that every resident will return.”

Now the NCI’s website lists this principle as “the opportunity to return/stay in the community.”

Quadel reports that “One-for-One Replacement does not mean that the unit mix of the demolished structures will be replicated in the new developments; [One-for-One Replacement] refers to the total number of replacement units produced.”

This means smaller units can be created in place of the six-person units that exist among smaller units in Barry Farms.

Quadel recognized NCI’s slow pace of transformation and recommended adjusting timeline and financial planning to improve both results and public confidence.

***

The news that on January 30 there was a Space Finding Bus Tour for business people searching for new commercial locations made residents wary of new progress on development. The bus tour meandered through Ward 7 and 8 and stopped in Barry Farms.

“They’re anticipating displacement,” said Pondexter-Moore.

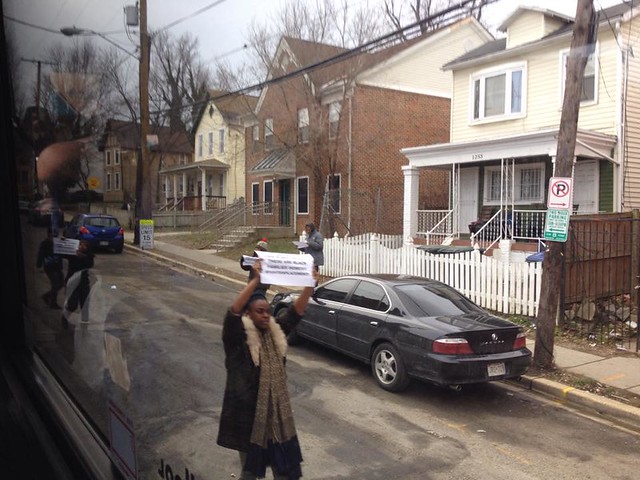

Empower DC held a meeting before the tour. Pondexter-Moore said the residents wanted to protest because they felt the bus tour was disrespectful. She drew a parallel between the bus travelling through Barry Farms and a safari.

When the bus showed up the protesters were ready with signs that read “Black Homes Matter.” They held the bus up for at least 30 minutes until the police arrived.

“We made them sit like a little child in the corner and think about what they are doing,” announced Pondexter-Moore at the Sunday forum.

Inside the bus the protest got people talking. Riders were uncomfortable and asking questions, according to Terry Scott, a Ward 8 resident who rode the bus looking for spaces to promote art in his ward.

According to Scott, someone from NCI spoke to the bus riders about opportunities available at Barry Farms and explained that the whole community would be demolished.

Pondexter-Moore said such blunt language is never used in community meetings or in front of the City Council. “They say, ‘we’re going to redevelop and everyone’s going to come back.’”

***

The forum began with a trailer for a documentary by Tendani Mpulubusi El on the history of Barry Farms. The land was bought from the Barry family by the Freedman’s Bureau during Reconstruction. African Americans, including some former slaves, were allowed to own small plots on the farm and run businesses.

Mpulubusi El’s explained that he wanted to spread an understanding of the history of Barry Farms to develop pride among the residents. The historical significance of the place signaled to some not only a new source of pride but a new way to prevent redevelopment. Attendees proposed that acknowledgement from the Federal Historic Preservation board might prevent Barry Farms from being demolished.

Forum moderator Max Ramone, leader of a campaign against demolition of public housing in Miami, noted the possibility but warned that similar status did not protect a community he worked with in Florida.

“They designated four houses as a museum to the black people who used to live there,” Ramone said.

DCHA maintains that Barry Farms is beyond repair and in need of redevelopment.

“These were built in the ‘40s,” Christy Goodman pointed out during an interview. “It’s our job at the Housing Authority to provide safe and healthy housing.”

Empower DC told forum attendees that engaging government officials and direct resistance—such as the bus protest—are two ways the organization works to prevent displacement.

Pondexter-Moore thinks Empower DC’s tactics have been working. She said NCI stopped applying for a large federal grant right before the deadline.

“We chose not to apply for the Federal Choice Implementation Grant because it would require we change the commitments we’ve made to the community,” Goodman explained. “DCHA will not break any promises we’ve made to residents.”

***

At the end of the meeting Pondexter-Moore suggested an “Occupy Barry Farms” movement might come to pass in the future. She asked people to provide their phone numbers so “at the drop of a hat” Empower DC could call their supporters and ask them to camp out in the community and prevent it from being bulldozed.

One attendee asked why the panelists weren’t in favor of working with the prospective developers and why they couldn’t just move to nearby Sheridan Terrace, now Sheridan Station.

Sheridan Terrace was a Ward 8 public housing project that sat vacant for ten years after the last resident moved. In 2008, when awarded federal “Hope VI” funding, DCHA moved to revitalize the project.

The Housing Authority sought out former Sheridan families and to-date has put 17 of them in rental properties. Two others were able to become homeowners.

Redevelopment of public housing takes time. Both Sheridan Station and Arthur Capper Carrollsburg—started in 2001—remain in progress and are often delayed due to market conditions, funding, and other factors.

“You asked why we don’t want to move to Sheridan Terrace? It’s not Barry Farms,” Phyllisa Bilal replied.

Another attendee, and resident of Barry Farms for 56 years, echoed the sentiment. “I raised 5 children here.” He said, “This is my monument.”

Fields lamented the love she used to find in “Cappers”, lost now that it is a mixed-income community.

Paulette Matthews, a resident for 20 years, appreciates the sense of community in Barry Farms. She says if a young mother needs to go to work or get food stamps, her neighbors will watch her kids.

She also enjoys decorating her front yard for Christmas and watching birds in her backyard.

***

One forum attendee feared that redevelopment would change D.C.’s and Barry Farms’ culture. She said that D.C. used to be called the “Chocolate City.”

Pondexter-Moore likened the Space Finding Tour and the redevelopment of “new communities” or “developing neighborhoods” to colonization. “It’s like you’re discovering something that already exists.”

She objects to the “concentrated poverty” theory to which she says D.C. government ascribes. Former Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner Gregg Justice expressed similar concerns during his tenure, requesting other wards share low-income housing placement to remedy the situation. According to neighborhoodinfodc.org, Ward 8 is the poorest ward in the District, with a poverty of 36 percent.

Pondexter-Moore says that the government thinks people of higher income will act as role models if they are mixed into lower income communities. She believes forcing the mixed-income transition is not a solution.

“You’re coming into a community and you’re telling people ‘this is how you should act’ and ‘this is how this should look’ and you’re making it for somebody else and you’re not uplifting the people that already live there,” Pondexter-Moore said.

Field said that in her mixed-income community, money is spent on things she doesn’t care about, like dog parks.

One attendee laughed at each mention of a dog park or ritzy restaurant.

“Don’t forget the bike lanes!” she said.

***

A press release sent out by Empower DC calls the New Communities Initiative and the Space Finding Tour racist.

“The reason that we say this is racist is because of the impact. It’s impacting a certain demographic. It’s impacting low-income blacks,” said Pondexter-Moore.

Professor Amanda Huron from University of the District of Columbia, gave a presentation on the changes she has studied in public housing at the forum. She said there had been a twenty percent decrease in public housing since 1963.

The community may need some revitalization. The historical documentary on Barry Farms shown at the start of the forum called the project “one of the most impoverished and chaotic communities in Washington, D.C. and the nation.”

When Paulette Matthews moved into Barry Farms in 1995, her brother asked her if she wanted a gun when she. She brushed it off.

Pondexter-Moore says that crime happens in Barry Farms but it happens in other communities too.

“I’m really really sick of public housing communities being held to a different set of standards than other communities,” she said. “You don’t solve crime with displacement. You don’t give people jobs with displacement.”

“There’s no doubt about it that Barry Farms needs improvements and repairs,” Pondexter-Moore acknowledged. But, she says, there are ways to avoid displacement and uplift the community. “The way the city has been doing it has been a catastrophe.”

***

The people at the forum had some new ideas to suggest.

Empower DC wants to incorporate the community so they can take ownership of their neighborhood and bring in their own businesses.

Matthews, a panelist on Sunday, said, “It’s just a matter of redoing the homes so people can live here.”

Matthews suggests they renovate the homes street by street and have people fill the vacant units while waiting to move back into their homes. She thinks this would keep people in the community and decrease the time spent waiting to move back home.

Previous renovations weren’t sufficient and didn’t revitalize the community. Matthews thinks “they didn’t even want us in the beginning,” because “they used the cheapest everything.”

Instead of beginning to build new homes for the current residents, former-Mayor Gray’s administration began work on a new recreation center. Empower DC protested this because the old rec center had to be demolished first, removing one of the last places for children to play.

The new Barry Farm Aquatic Center, an indoors facility complete with spiraling slide and water jets shooting above the surface, opened in December 2014.

“What’s the point if we’re not going to be able to enjoy it?” said Matthews. “They could have made homes instead.”

***

“Under the previous administration, they failed to meet the needs of the most vulnerable citizens,” said the communications Director at the Deputy Mayor of Planning and Economic Development. “The Bowser administration will speed up the process by recommitting to the New Communities Initiative by creating quality units for residents and making sure that current units are safe and sound.”

Pondexter-Moore hopes that the new mayor will change things.

Empower DC and the Barry Farm Tenants Association will be meeting with Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development in March to discuss how the city plans to fund the project.

When asked how Empower DC and the Barry Farms tenants will prevent displacement, Pondexter-Moore said, “We are willing to do whatever it takes.”

One panelist, Ari Theresa, a Howard Law graduate and someone who works closely with Empower DC in Barry Farms, seemed similarly determined.

“We have some tricks up our sleeves,” he said.