Raised in Southeast D.C. during the crack epidemic, Rodney Stotts, now a 50-year old man, became involved in illegal activities as a young person. But that was another lifetime for Stotts. Now, he is a licensed master falconer — the highest level in the sport — and one of the few Black falconers in the country. Stotts is breaking boundaries by pursuing falconry, a predominantly white field, in order to help those around him.

Approximately an hour’s drive from Washington, D.C., Stotts works with his birds in a former insane asylum down the street from a juvenile detention facility. He joked that people mention they feel the spirits of former asylum patients when they visit his program, but he believes that as long as he keeps to himself, the spirits will do the same.

Stotts now runs Rodney’s Raptors, an organization through which he offers educational programs on raptors, a sanctuary for the birds, training in falconry, and photo opportunities.

As he joked about the location, Stotts was keeping Raven calm by speaking to him in a hush but strict manner. Raven, a 7-year-old red tail hawk, stayed perched on Stotts’s hand and wildly flapped his wings every once in a while. For the average person, this is a frightening sight — but Stotts kept him under control with ease.

He cares for and trains three birds of prey at the institution-turned-sanctuary. They’re like family, and some are named for loved ones who have died. Stotts’s license allows him to trap new juvenile birds each year, releasing them when they reach maturity, more fit from their training with Stotts. While he loves the outdoors and prefers his birds to most people, his dedication to falconry as a profession comes from his commitment to local youth, so more young people may have the chance to work with the magnificent creatures. It was a giant Eurasian eagle owl, Mr. Hoots, the first raptor to perch on Stotts’s arm more than 20 years ago, that changed his life. Mr. Hoots is unreleasable and is in his care today.

Video of Stotts releasing the first bird of 2014 he had trapped, named Keisha after a loved one. Video courtesy of vsky / YouTube

During his 20s, in and out of selling drugs, Stotts’s path to birds began with Earth Conservation Corps, where he took a job in order to have a legitimate pay stub when applying for an apartment. The group had just formed to clean up the Anacostia River, mostly recruiting young workers from the Valley Green Community housing project.

The conservation work wasn’t limited to trash cleanup. Stotts helped care for injured birds and was a part of reintroducing bald eagles on the Anacostia, where they can be spotted today. His supervisor, the founder of Earth Conservation Corps, was a falconer and introduced Stotts to Mr. Hoots. Stotts was hooked and eventually led the raptor portion of the organization’s program, Wings over America, which assigns youth who have been arrested to care for injured birds of prey.

The girls’ and my most recent bird spotting in #RockCreekPark… a bald Eagle. Not gonna lie, it was cool. pic.twitter.com/dvKeruK35c

— Robert C. White, Jr. (@RobertWhite_DC) April 17, 2021

Growing up, Stotts had a natural connection to animals. While he spent the majority of his youth in an urban neighborhood east of the Anacostia River, he occasionally spent time at his grandmother’s home in rural Virginia that was filled with a variety of creatures. “I knew I was always gonna end up working with some sort of animal. I had animals my whole life — white mice, tree frogs, crayfish, snapping turtles,” Stotts said.

Hollis Wright met Stotts while he was working with the Earth Conservation Corps. It was a life-changing experience for Wright, a 19-year old man at the time who described himself as a “youth on the fringe.”

“It was different. I remember not being really into it,” Wright said. “I’d grown up [as] an inner-city youth — you don’t really experience certain things. Usually, anything dealing with nature was outside-the-box thinking for me.”

Within a year, Wright graduated from the program and continued a lifelong friendship with Stotts. Wright considers Stotts as a family member, referring to him as his uncle.

“By the time I graduated, I saw where the passion came from,” Wright said. “After meeting Rodney and getting to know him and hearing some of his stories … it became apparent that it wasn’t fake. It was all genuine and pure with him.”

Wright’s experience at high school was “extremely different” than his time with the Earth Conservation Corps. A large influence was the connection he cultivated with Stotts during his time at the program.

“Having someone with a similar background, and having lived certain experiences, and still being able to be a person, to be open and honest and appreciative and loving and caring: It let me know that maybe the road I was on wasn’t the right one,” Wright said.

Ten years ago, Stotts began Rodney’s Raptors. The main motivation for this move was because Stotts felt limited by which groups of young people he interacted with.

“I started Rodney’s Raptors because the program that I worked for was for adjudicated youth,” Stotts said. “So you got 16 and 17-year-olds, never been locked up, and they wanted to learn this, they wanted to join. I had to tell them, ‘Go get locked up. Now come back.’ Which was the stupidest thing in the world.”

Throughout the decade that Rodney’s Raptors has been in existence, Stotts and his birds have interacted with hundreds of people across a variety of backgrounds.

The importance of extracurricular learning

From the racist history of standardized testing to D.C. public and charter schools disproportionately suspending and expelling low-income students, schools can feel like jail. And while education is primarily expected to occur within school walls, using a pen and paper, this can promote anxiety for some students, which hinders learning and growth. In March, 32% of adults in D.C. lived in a household with children who experienced anxiety, nervousness, or feeling on edge, according to D.C. Kids Count.

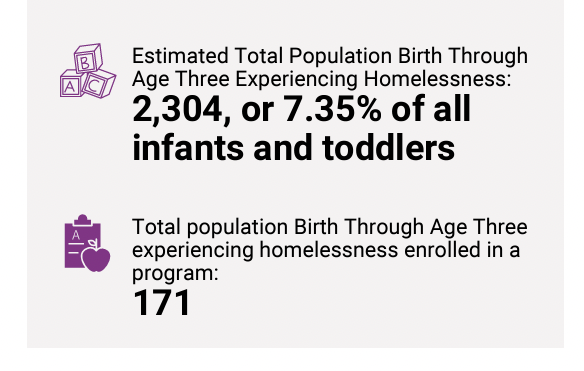

In addition to this, many low-income or homeless children are left with limited access to extracurricular activities, which, according to the Cornell Policy Review, allow children and adolescents to develop an identity and critical socio-behavioral skills that then influence academic success, such as interacting with peers and mentors and working on a team. Children and youth in the Ivy City neighborhood in Northeast, for example, had nowhere to play but in the street until recently, according to Sebrena Rhodes, a community organizer for the grassroots organization Empower D.C.

[Read more: Ivy City residents gain little amid development boom]

The nonprofit has been organizing residents since at least 2008 in a campaign to turn a boarded-up historic schoolhouse in the neighborhood into a recreation center. Community calls for this use of the school began 40 years ago. For years, a member of the organization has provided “the only basketball court in Ivy City” in his yard. And last year, Empower D.C. opened Ivy City Clubhouse, a community-run space for school tutoring and fun activities to keep young people safe and engaged.

The redevelopment plan for the school now includes a recreation center but residents say the restoration is not happening fast enough.

Longtime residents of Ivy City, worried their NE community is being overrun with new development, gathered late today to urge DC Deputy Mayor to speed up restoration of the old Crummell school into a community center and play space for old and young alike. @kojoshow @wcp pic.twitter.com/TeIO3x9jAi

— Tom Sherwood (@tomsherwood) March 30, 2021

“We just didn’t create better extracurricular activities, we provide activities and create community events, food, snacks, toys, books, computers, youth leadership and participation and many other resources that’s provided to their families,” Rhodes said. “When our families are healthy, safe, and respected, the children will feel safe and strive to do their best.”

Without adequate neighborhood spaces and resources to foster community, young people can turn to illegal activities or unproductive ways to fill their time. In-depth research published by the Chicago School of Criminology in 1942 identified that weak neighborhood structures like poverty are linked to higher rates of juvenile delinquency — findings that remain widely accepted academically, but unaddressed in many communities.

Now more than ever, outside-the-box educational opportunities are pivotal for student engagement and interaction. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced young people to spend an entire summer and school year doing online learning. This results in a lack of daily interaction with teachers and peers, which can result in mental health deterioration and learning delays.

[Read more: Community organizations face difficulties providing vulnerable children with wellness support during the pandemic]

From moving mid-year due to evictions to teenagers under pressure to work and make up lost family income, young people are under tremendous stress. For some, particularly those with existing mental health conditions, minimal socialization can lead to suicide and self-harm, which doctors at Children’s National Hospital say is on the rise. D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Lewis D. Ferebee has acknowledged the growing crisis and agreed to allocate $5 million dollars for training teachers on mental health.

The coronavirus pandemic disrupted the everyday lives of most people around the globe, and Rodney’s Raptors was no exception. As the core of Stotts’s work is interacting with people, social distancing measures made his job difficult. Throughout the pandemic, Stotts has been able to do small outdoor events for birthday parties, but he has been unable to reach the same amount of people pre-pandemic.

Fortunately, earlier this year 102 people donated nearly $4,000 to a GoFundMe set up by one of Stotts’s supporters to help him purchase a laptop and recording equipment so he can continue his work virtually. He has obtained the equipment and is working on designing the best virtual education experience he can. Stotts said there is no substitute for the in-person experience with his birds, but he will be able to reach hundreds of more people, both people isolating during the pandemic and opening up to young people across the country.

In the past year, Stotts and his story have received an enormous amount of attention, buoyed by a documentary of his life, “The Falconer,” directed by Annie Kaempfer. The film explores Stotts’s past and present while bringing attention to racial injustice and environmental racism.

Despite the documentary’s acceptance into the Atlanta Film Festival and such, Rodney’s Raptors remains running entirely on donations.

Helping youth before incarceration

instead of responding to it

Peter Tatian, a community development expert with the Urban Institute, spoke to Street Sense Media about attending one of Rodney’s programs in 2015.

“I was very impressed with Rodney and his commitment to — and passion about — these birds of prey that he was trying to educate people about,” Tatian said. He recalled the crowd’s enthusiasm and interest and spoke to the importance of role models originating within the community.

“Maybe for some people it would be surprising that there’s somebody like Rodney living in this community that has this interest,” Tatian said.

For his part, Stotts said in a 2015 interview with the George Washington University Hatchet that being seen with his birds is enough of a shock to stop traffic, but not always in a positive way. “I’ve had police officers pull me over, guns drawn, everything: ‘Get out of the car! Lay on the ground.’ Then they read one piece of paper that says ‘U.S. Fish and Wildlife federally licensed falconer,’ and then it becomes ‘Oh my god, you do what?!'”

Tatian said amplifying community voices and changing those individual perceptions is crucial. Stotts is one of roughly 30 Black master falconers in the entire U.S. and overcame significant racism to succeed in his field, but he must still break stereotypes.

“I think that just shows sometimes we don’t all appreciate how much there are these assets in our communities and how there are many people who have a lot to offer, and we just need to give them more opportunities to share what they know and what they’re passionate about.”

Tatian said outside-the-box learning possibilities are significant because different people respond to different approaches to education. “We need to engage with people not only in the classroom but outside in different ways, so that we can really help each person find something that really inspires them and can be a basis for them succeeding in school and in life going forward,” Tatian said

For someone like Wright, who now has a family and works in law enforcement, Rodney inspired him to turn his life around and change for the better. They stay in touch and Wright helps Stotts out every once in a while.

Stotts compares the birds he cares for to the young people he works with — many of whom remind him of himself as a youth.

“If someone don’t step in and help them and guide them in a certain way, there’s only one or two options. You either end up in jail or dead,” Stotts said. “So the same way with the birds, if someone, if a falconer didn’t step in and get that bird, catch them, [they would not survive],” Stotts said. The majority of young birds of prey do not make it through their first year of life. “Now come springtime of the next year, [if a falconer cared for it] that bird got an 85-90 percent chance of survival and reproducing.”

CORRECTION (05.05.2021)

This story has been updated to correct the caption under the video of Stotts releasing a bird, Keisha, in the trailer for his children’s book. The caption had previously said it was the first bird he ever caught, but Keisha was the first bird he had trapped that year. The first bird Stotts ever caught was Monique, a North American Kestrel.