Content warning: This article discusses gun violence.

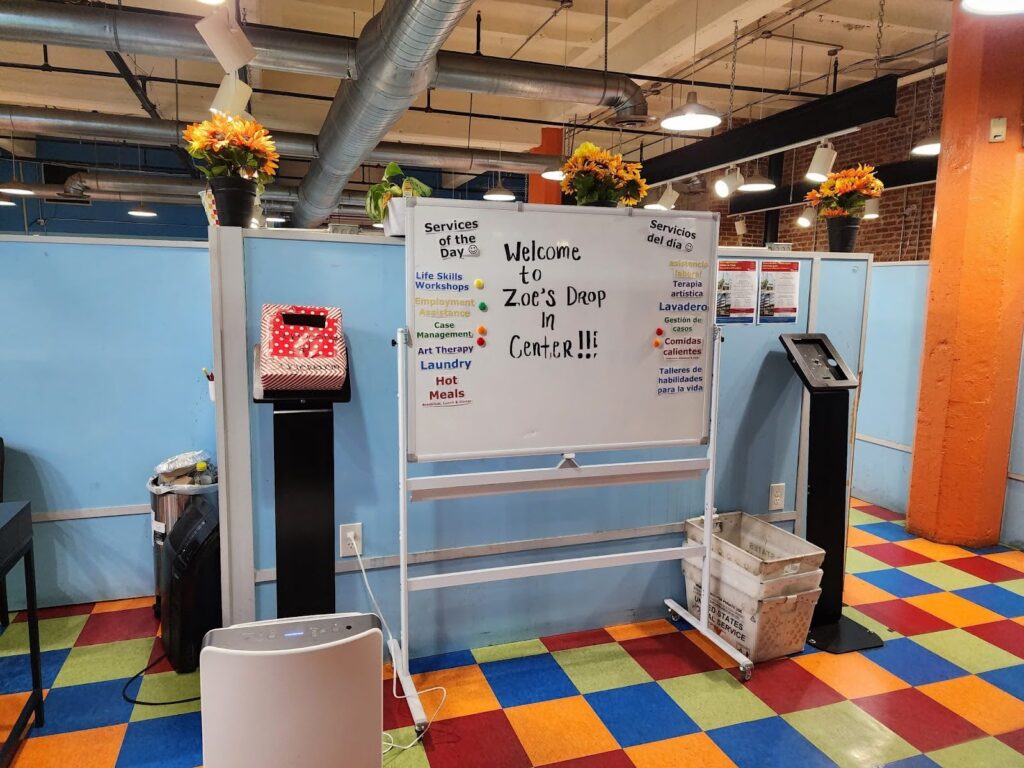

From the vibrant colors and the welcoming atmosphere at DC Doors, the tragedy that befell this community seems, at first glance, inconceivable.

Since its opening in 2011, DC Doors has become home for dozens of young people experiencing homelessness, especially people who identify as LGBTQ+. One of three youth drop-in centers in the District, it offers transitional housing and services catered to young people. Established to fill the gap in housing needs in the Latino community, DC Doors primarily serves Spanish-speaking youth.

Last year, a longtime resident and staff member, 23-year-old Brandon Lewis, was shot and killed by another resident within the facilities of DC Doors. Within minutes, all residents and staff members had to be evacuated. The drop-in center finally reopened on Christmas Day after weeks of closure. But the shooting still casts a palpable shadow over the community.

“We had all the walls repainted,” said Janethe Peña, founder and executive director of DC Doors. “We used to have murals, but they became a trigger. We didn’t want residents and the staff to associate the murals with the incident, so we repainted the walls in white to symbolize a fresh start.”

Peña was off work the night of the shooting, only rushing back after receiving multiple phone calls from her coworkers. Once at the scene, she helped obtain the footage, secure the facility, call the shelter hotline, and ensure the young people who were displaced had a place to go, she said, recounting the frenzy that followed the shooting.

“We had many migrant youths who didn’t speak English. There was another layer of trauma for them because they had just traveled such a long way and they were being displaced again,” Peña said. “We didn’t have answers to anything.”

The trauma from the shooting became imprinted on the community, continuing after the facility reopened on Dec. 25, at a limited capacity. Peña said a few staff members resigned because of safety concerns.

“When I left DC Doors at 1 a.m. that morning, I just remember feeling so scared,” Peña said through tears. “And I thought, if I was feeling like this, I can’t even imagine how the staff who performed the chest compressions and the youths who saw the incident feel.”

Lewis, who was killed in the shooting, was housed by DC Doors’ extended transitional living project, which is intended for young people who have both a mental illness and a substance use disorder. Consequently, Lewis was a familiar face in the community as well as with shelter providers around the District.

“He had his quirks. What made him unique was the fact that, months earlier, he had assisted me in saving another young man’s life,” Peña reminisced.

“It really bothered me, because Brandon was such a light. I have known him since he arrived at DC Doors,” added Cilinia Whitted, who has worked at DC Doors for the past five years and was on shift the night of the shooting. “It still bothers me.”

Peña told Street Sense that she, along with many community members, had been requesting for the past two years that D.C.’s Department of Human Services (DHS) install security measures at DC Doors. DC Doors is “a low-barrier facility where we don’t ask questions for youths to enter,” she said, which makes security measures a priority.

“Prior to the incident, we would have to call the police every other day,” Peña said. “We had to de-escalate fights. We weren’t able to manage the youths coming here with arrays of issues, like being inebriated or having a mental health crisis.”

However, DHS, which contracts with DC Doors to provide services, only engaged in conversations on security after the shooting, Peña said. She was adamant about only reopening the facility once DHS implemented security measures.

DHS did not respond to Street Sense’s request for comment on the shooting and new security procedures in time for publication.

Since December, DC Doors has installed metal detectors, X-ray machines, door alarms, and more security cameras. DHS funded half of these security costs, while DC Doors covered the other half through fundraising. Peña said DHS also recently introduced new security measures at the other two youth drop-in centers in D.C. — Sasha Bruce Youthwork and Latin American Youth Center.

“To be honest, it took the life of a youth for DHS to take action. That really hurt us,” said Lady Ventura, a 23-year-old resident of DC Doors, at an oversight hearing on Feb. 29. “[Lewis] was part of the DC Doors family.”

DHS, shelter providers, and residents often disagree on the extent to which security measures are necessary. Security measures, which can prevent weapons from being carried in, can also be invasive, creating an air of surveillance.

“I have witnessed a lot of drug addicts in other shelters where I haven’t felt safe,” testified Maria Rivera, a current resident of DC Doors, at the hearing. “I have met a lot of genuine people here. I think they deserve opportunities to join programs where they are accepted for who they are.”

At the hearing, Theresa Silla, executive director of the Interagency Council on Homelessness, said implementing security measures at youth drop-in centers like DC Doors was a “delicate situation.”

“This is a double-edged sword,” Silla said, referring to the installation of security features and the hiring of security personnel. “This prevents some youths from accessing critical services but inspires feelings of safety and security for other youths who want to access those same services.”

In her interview with Street Sense, Peña refuted the claim that security measures turn young people away. According to her, the security measures put in place have been successful — the only emergency phone calls DC Doors makes now are medical calls.

“The youths who really need the services are the youths who are going to come,” Peña said. “You can ask anyone here and they will tell you that we feel much safer. The presence of a security guard — not even a police officer — sets the tone of safety.”

This was corroborated by Carlos Martinez, a resident of DC Doors, who told Street Sense that he felt much safer after the drop-in center reopened with security measures. Like Ventura, he said security measures should have been implemented long ago.

“This is a safety issue not just for the youths, but for the staff too,” Whitted said in her interview with Street Sense. “Attendance has decreased, but DC Doors feels a lot safer now.”

While there are similar tensions at adult drop-in centers, the facilities have long been required to adopt security measures. Youth drop-in centers should, therefore, have such security measures too, Peña added.

Several residents and former residents of DC Doors showed up to the Feb. 29 hearing to share their experiences with the youth drop-in center with the Committee on Housing. Each spoke highly of the inclusive environment, which, to them, sets DC Doors apart from other youth drop-in centers and homeless shelters. Many residents who testified identified themselves as members of the LGBTQ+ community.

“As a young gay person out here homeless, I had people judging me for who I am. Once I went to Zoe’s Doors, once I started talking to some of the LGBT youths, I decided this was the perfect place I needed to be,” said Demetrius Hall, a former resident and subsequent youth advisor at DC Doors.

DC Doors also assists residents in obtaining birth certificates, social security numbers, food stamps, and supportive housing and provides food, clothing, showers, laundry, therapy, life skills classes, and job advising. Residents testified that they found jobs and housing through DC Doors.

“Many of the youths who wind up homeless have been failed by our system,” said Joseph McGee, a 22-year-old resident of DC Doors and a student at Montgomery College. “We need more places like DC Doors.”

Editor’s note: Some quotes from the residents of DC Doors have been translated from Spanish.