In 2022, a man committed a series of attacks against homeless people in D.C. and New York, killing two people and injuring three. The attacks raised awareness about violence against people who lack stable housing, but they’re far from the only threats.

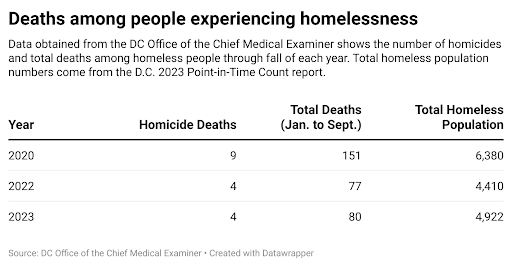

In 2020, nine people experiencing homelessness were victims of homicides in D.C., according to data from the medical examiner’s office. At least four homeless people were murdered in 2022, and another four have been killed in 2023, data obtained in a Freedom of Information Act request showed.

A Street Sense analysis of that data found that in 2022, people experiencing homelessness were over twice as likely to be the victim of a homicide than someone who was stably housed.

“It’s dangerous out there, period,” said Rachelle Ellison, assistant director of People for Fairness Coalition, an advocacy group of people who are currently homeless or have previously experienced homelessness. “The crime rate, that’s so high now, has just enhanced it.”

The District has seen a 40% increase in violent crime overall in the past year, sparking concerns about public safety in the city. The Metropolitan Police Department provides public data on crime rates, but it doesn’t track victims’ housing status, a representative from the police department wrote in an email to Street Sense, making it difficult to tell how many people experiencing homelessness are affected by crime each year. But it’s safe to say people who sleep outside are being impacted by the rise in violent crime, Ellison said.

“There’s an increase in violence against the homeless because they’re vulnerable,” Ellison said.

Research shows people experiencing homelessness are far more likely than housed people to be the targets of violent crime. A study conducted across five cities in the United States in 2014 found 98% of participants experiencing homelessness had been victims of a violent attack, with 73% experiencing an attack in the last year. Over a quarter of participants said they’d been attacked four or more times.

People experiencing homelessness are subject to many different kinds of violence, including hate crimes, violent robberies, sexual assault and domestic violence.

Attacks can come from both people who are housed and unhoused. One study found 30% of victims reported being attacked by someone who was housed, while 32% reported the attacker was homeless. Fifteen percent of people who were attacked reported they thought it was a hate crime. Another quarter didn’t know why they were attacked.

Ellison said she was homeless in D.C. for 17 years before she secured stable housing through Pathways to Housing, a local social services organization. She’s spent the last 15 years housed, healing and recovering from her time sleeping outside. Now, she’s helping others get off the streets.

“The violence is real, and it’s even worse now, especially for women,” Ellison said.

One significant risk for women experiencing homelessness is intimate partner violence. Research on the types of violence homeless women experience shows they’re more likely to experience violence before, during and after homelessness than the general population. They’re also more likely to report experiencing intimate partner violence than homeless men.

That same study found most of these experiences don’t get reported to authorities, highlighting the need for alternative services for women at risk of homelessness and domestic abuse.

Michelle Sewell, the crisis shelter director at DC SAFE, an organization that helps families fleeing domestic violence, said the center saw the number of calls it received more than double after the start of the pandemic in 2020 — increasing to 11,000 calls. The calls still haven’t slowed.

The best way people can protect themselves is by connecting with resources and securing safe housing away from abusers or perpetrators, Sewell said. For instance, DC SAFE recently opened a new temporary emergency shelter for domestic violence survivors that has 30 apartment-style units in Northeast D.C.

“Identify who your supports are,” Sewell said. “What’s your community? Can you go towards that community?”

However, accessing resources isn’t always easy. In some cases it can be difficult for victims of violence to access services like shelters because perpetrators will wait for them there, Sewell said.

When she first became homeless, People for Fairness Coalition outreach worker and Street Sense vendor program associate Nikila Smith needed a tent. Soon after she moved to D.C., she met a man who let her use his. However, he quickly began stalking and harassing her, saying she was “his property.”

“Whenever I went to Miriam’s Kitchen, he was there waiting for me,” Smith said. “So I told one of the case managers, she helped me get a taser.”

Smith had other encounters with men who wouldn’t leave her alone and prevented her from accessing services, like showers at the day center.

“It was just horrible, to the point where I had to go to the director of the day center and say something to her,” Smith said.

But she was told the other people in the day center had a right to use the services. “So how’s their rights more important than me?” Smith said.

One way to help keep people safe is by offering private spaces, like apartment-style shelters, which Ellison said she believes people are more likely to use. She hopes that as D.C. opens more non-congregate shelters, people who are affected by violence will feel safe moving inside.

While people report the majority of attacks occur outside, 13% of victims reported experiencing violence in a shelter.

“Some people are introverts and have a problem with large crowds of people that they don’t know, and then they’re scared because there’s violence there,” Ellison said. “So if you’re in an apartment-style shelter, you feel more safe.”

For those who sleep outside, staying in places with a police presence nearby can help increase personal safety, Ellison said, such as areas near the White House. For women, dressing more like men can also help keep away unwanted attention, she said.

Women are more of a target when they’re alone, Ellison said, so staying in groups and forming communities can help keep them safe.

“That’s what I did when I was out there, but I always ventured off, and that’s when I got in trouble,” Ellison said. “That’s when the violence came.”

However, keeping communities together is becoming increasingly difficult amidst the city’s crackdown on encampments, a practice that makes it difficult for people to remain connected with case managers and other services. City officials closed at least 14 encampments in 2023, and federal officials closed McPherson Square, displacing at least 70 residents, many of whom remained unhoused.

Despite the barriers to accessing services, the best thing people can do to stay safe is to plug into services such as shelters, connect with case managers and try to work toward stable housing, Ellison said.

“Believe in yourself and maybe give yourself a chance to go into a shelter or domestic violence shelter or transitional house drug treatment,” she said. “Give yourself an opportunity just to live a normal life. There is hope, because I was able to do it myself.”