D.C. is closing more encampments this year — and some with just one day’s notice.

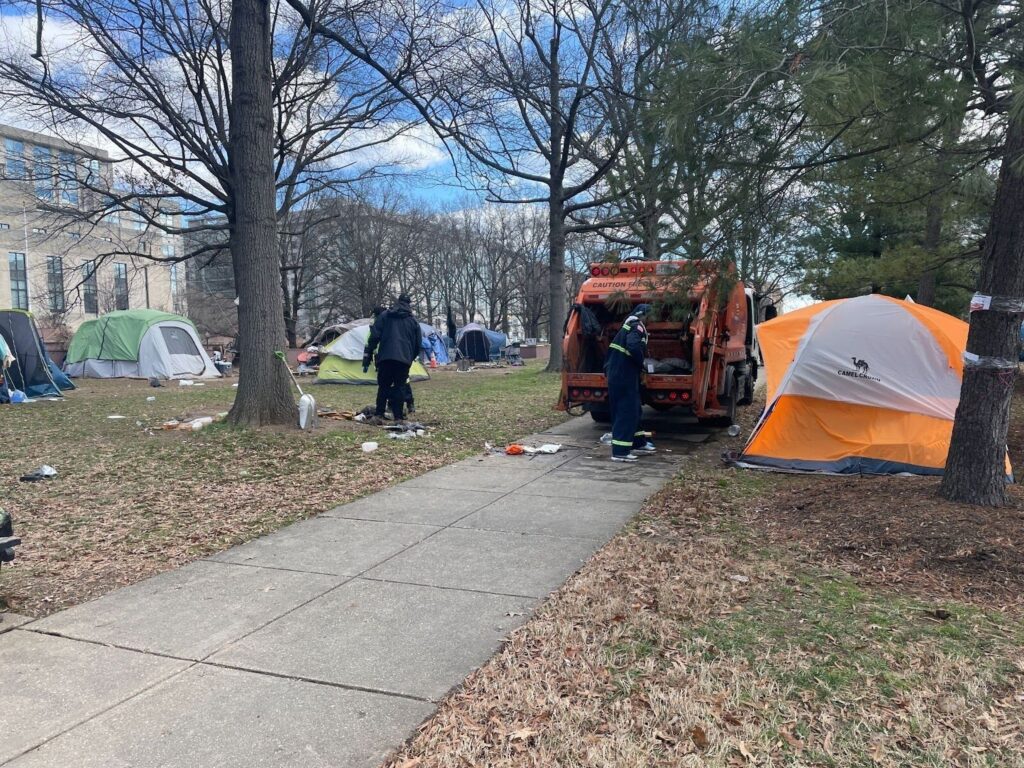

For years, D.C. has banned camping on public land and parks, enforced to varying degrees by the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS). Encampment residents grew accustomed to moving their tents and belongings outside “clean-up zones” established by DMHHS before returning to set up camp again.

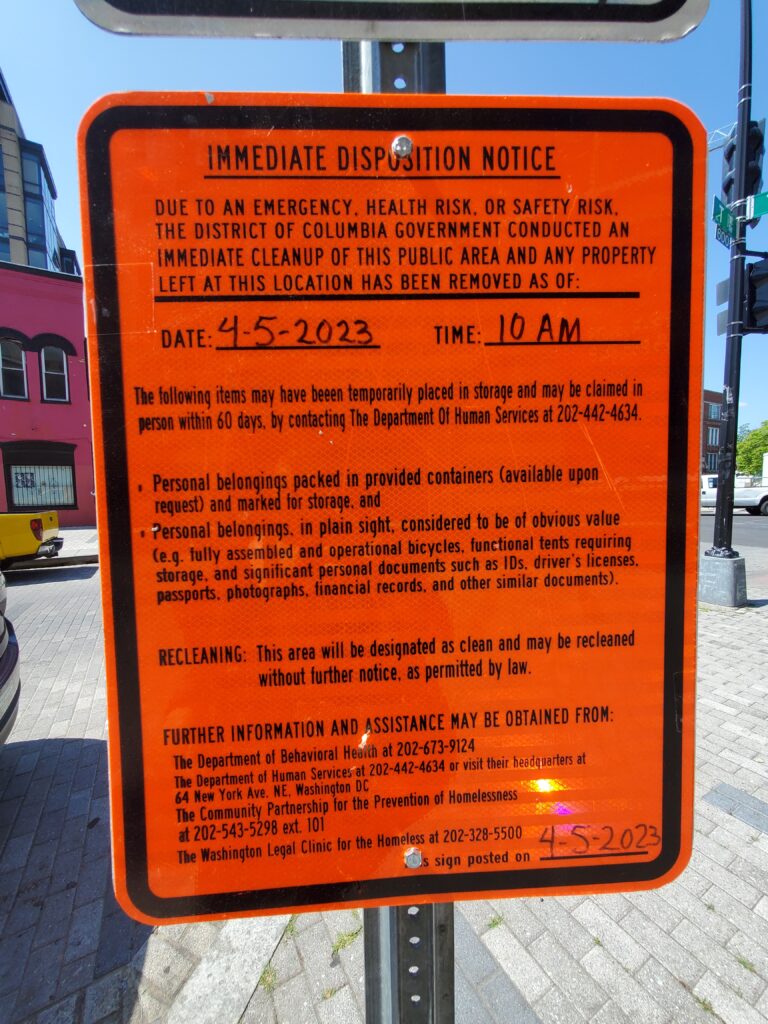

But over the past year, D.C.’s approach to encampments has shifted. DMHHS now closes sites permanently at a greater frequency, prohibiting encampment residents from returning. An increasing number of these encampment clearings are conducted under the guidance of “immediate dispositions,” where the city provides unhoused residents at these sites between 24 hours and six days’ notice before permanently closing their encampments.

From 2019 until 2021, DMHHS conducted an average of seven immediate dispositions each year. But in 2022, that number spiked to 59. DMHHS has conducted over 39 dispositions thus far in 2023, according to the office, affecting at least 36 residents. DMHHS has cleared sites near Dupont Circle and the 600 block of T Street Northwest multiple times.

Immediate dispositions, unlike regular encampment clearings, are not posted online or shared with the public — prompting outreach workers like Danica Hawkins, the encampment coordinator with Miriam’s Kitchen, to worry this rise in encampment closures will go unnoticed.

“It seems like everything’s happening completely under the radar,” said Hawkins. She referred to the February closure of McPherson Square, which received international attention when 70 residents were displaced. “You saw how much pushback McPherson Square got. It’s absolutely no surprise that now encampment evictions are going to be done swiftly, with next to no notice.”

The rise in immediate dispositions has alarmed advocates and outreach workers, who say the practice harms residents and does not adhere to the city’s published encampment protocol. The policy generally requires DMHHS to provide 14 days’ notice before closing an encampment in what is known as a standard disposition and to use immediate dispositions only in emergency circumstances.

Ann Marie Staudenmaier, senior counsel at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said waiving the requirements without good reason goes against why the encampment protocol exists — as does the city’s increased use of the immediate dispositions over the past year.

“When they’ve done them in the past, when they were doing them in the fall, they didn’t seem to be justified,” she said.

Residents displaced

All immediate dispositions are site closures, but the reverse isn’t always true. In addition to the 39 immediate dispositions, DMHHS closed at least eight encampments in 2022 and again in 2023, and officials are now widely enforcing the no-camping policy, including in District parks. The National Park Service also closed several sites in the last year, most recently at McPherson Square in February.

“They’re basically closing off any part of the city that would normally be full of tents, and causing people to have to go to more and more remote places or more and more dangerous places,” Staudenmaier said.

The increase in closures and immediate dispositions does not reflect a change in policy, but is instead a response to an increase in unsheltered homelessness, DMHHS officials said.

“All immediate dispositions during the 2022 and 2023 calendar years were conducted according to the established District protocol,” Deputy Chief of Staff Jamal Weldon wrote in an email to Street Sense. “The increase of these engagements was due to the increase in public health and safety intrusions that warranted these actions.”

Encampment residents, advocates and homeless service providers say the increase in closures means more encampment residents are being displaced and losing contact with their case managers.

As the city closes large encampments, some residents have moved to smaller ones. Two residents at encampments shut down in the last two months who had come from McPherson Square both said they relocated to another park because they had not received the services needed to move into housing. Residents who were offered beds at low-barrier shelters turned them down in fear of their safety, hygiene and losing their autonomy.

“It’s pretty tough, you know,” said Moe, whose encampment was marked for an immediate disposition on May 25. He and his partner Jackie had been sleeping in LeDroit Park for two days when a city worker pinned a note to the lime-green umbrella sheltering their belongings. The notice said they had two days to leave because the city planned to close the encampment.

DMHHS did not specify a reason for the closure in its email notifying outreach workers contracted by the city.

Moe had been couch surfing for about a month. After exhausting other housing options, he moved into the park.

“We’re not bothering anyone,” Moe said. “No one seems to care enough to come ask us themselves if we’re okay.” Moe shared only his first name due to the discrimination people experiencing homelessness often face.

The rise in immediate dispositions

For standard dispositions, DMHHS usually posts a notice on its website and at the encampments two weeks before a clearing. Unsheltered people living in the area who feel uncomfortable staying in shelters spend those weeks figuring out where they’ll go. Generally, finding permanent housing in this timeframe is not possible. The process takes at least six months with a voucher administered by the Department of Human Services and the D.C. Housing Authority.

DMHHS reduced the number of full encampment clearings at the start of the pandemic. This adhered to March 2020 guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to avoid displacing encampment residents at the risk of spreading COVID-19 and disrupting residents’ access to homeless service providers.

Beginning in summer 2022, however, DMHHS began clearing encampments at a faster pace, relying on immediate dispositions. According to the city’s encampment policy, DMHHS is supposed to conduct immediate dispositions only in the case of an “emergency, security risk, health risk or safety risk.” Staudenmaeir said when the Legal Clinic worked with the city to draft the encampment policy, the attorneys involved expected immediate dispositions to be used only when it wasn’t possible or advisable to wait 14 days to close an encampment, such as a tent blocking the road.

In response to questions, DMHHS provided a wide list of reasons for conducting immediate dispositions, from the presence of propane tanks to proximity to traffic. Blocking a pedestrian passageway was one of the most commonly cited reasons; others involved occupancy of private land, abandoned property or city parkland. D.C. also uses immediate dispositions to clear sites where DMHHS has previously removed an encampment, arguing that full notice isn’t necessary given the past closure. DMHHS does not always include a reason for closing an encampment when it notifies outreach teams, according to emails obtained by Street Sense.

“The reason for an immediate disposition can vary and are generally site specific.” Weldon wrote in an email to Street Sense, in which he provided reasoning for the immediate dispositions DMHHS has conducted this year. While Weldon said each of the immediate dispositions was allowed under the city’s encampment policy, advocates worry the stated reasons may only justify standard dispositions, not the urgency of an immediate disposition.

DMHHS often sends outreach workers notice of immediate dispositions at 4 or 5 p.m. the day before, which Hawkins, the encampment coordinator at Miriam’s Kitchen, said leaves her and her colleagues scrambling to find options for encampment residents. DMHHS leaves tags on encampments to notify residents a day or two before the disposition; in some cases, the signs say that officials may conduct an immediate disposition with no notice if a site has been cleared before.

“We have no time to prepare. We have no time to advocate for our clients. We are losing our ability to build rapport if people keep being pushed around,” Hawkins said. “At no point can I guarantee that they’re going to be in a safe spot. And clients don’t know either. They come back, and all of their stuff is gone.”

At an immediate disposition on the same day as Moe’s and not far away, an encampment resident said he expected he and others living there would move back into the area within a few days. He gave his name as Nephew, using an alias to protect his privacy as he spoke about his prior incarceration and drug use.

The city clears the area every three weeks or so, which Nephew said is disruptive and irritating. His encampment, on the sidewalk across from the Howard Theatre, wasn’t a typical one with tents in a park, but rather a collection of between eight and 12 people who would sit outside on chairs during the day.

The group, which includes several people who appear to be elderly, doesn’t really want to be out in the open — they used to be on a grassy area but that was fenced off. Then they moved into an alley, now also blocked off. And no matter how many times the group is forced to move, Nephew finds the repeated site closures don’t help residents get housed and sober.

“I’m not saying it’s right but I’m just saying they’re taking [our spaces] away,” Nephew said.

D.C. is closing more encampments

Immediate dispositions are part of an overall increase in encampment closures in the District.

Encampment clearings wound down when the pandemic began, going from 111 clearings in 2019 to 75 clearings in 2020. To follow CDC guidance, DMHHS began conducting trash-only clearings whenever possible — leaving tents untouched. In 2020, DMHHS conducted 40 trash-only clearings, 21 full clearings and six immediate dispositions.

Site closures took off in 2021, with the launch of the Coordinated Assistance and Resources for Encampments (CARE) Pilot Program, which theoretically paired encampment closures with housing vouchers for displaced residents. While advocates and DMHHS disagree about the success of the CARE pilot, Staudenmaier said the end result has made way for more blanket site closures.

One rationale DMHHS is using for these site closures is the District’s 2016 ban on camping, which the agency used as the sole justification for closing encampments on March 14 and May 25. The city is also now enforcing the no-camping rules in all D.C. Department of Parks and Recreation sites.

“Technically and legally, yes, no one’s supposed to be in any of these spaces,” Staudenmaier said. “But the protocol is supposed to give [D.C. officials] a remedy if they’re concerned about tents being in a public space. And they’re kind of bypassing that remedy by just closing off all these spaces and saying okay, well, no one can ever come back here.”

When D.C. closed the K Street Northeast underpass, which dozens called home until January 2020, Clifton Waldrop and two other encampment residents moved to a spot on First Street Northeast, just across the block. The three of them lived there until this year, when the site was permanently closed on June 1.

Waldrop said he adjusted to First Street, although the prior spot “was a little better because it was an overpass.” He said he filed for a housing voucher in 2000 and received one in February 2023. But he is still waiting to move into housing and had to relocate to another encampment a few blocks away on the day of the site closure.

Is the encampment policy effective?

DMHHS says the rise in encampment closures is due to an “increase in public health and safety intrusions.” There are many reasons for this. More people are living on the streets, according to an annual census of people experiencing homelessness. And site closures happen commonly in areas where businesses have filed repeated complaints, or in areas that are slated to undergo development.

“The truth is, it’s an eyesore,” said Faheem Smith, the building coordinator for 111 K Street NE, which is a business that rents out office space to other businesses. The firm has asked the city to remove nearby encampments for the past five years, citing the presence of trash, needles and rats around the building and multiple conflicts between encampment residents and employees. The business wrote a letter to Mayor Muriel Bowser last month asking the city to remove the encampment on First Street Northeast.

Similarly, DMHHS closed an encampment outside the Church of the Epiphany on April 27, after nearby businesses on the 1300 block of G Street Northwest complained about it for four years, according to the church’s rector, the Rev. Glenna Huber.

DMHHS conducted a site closure at an encampment near 111 Massachusetts Ave. NW on April 20, citing a severe rat infestation. The encampment sat in front of an office building bought by Georgetown University, to be converted into student housing beginning this May, according to a university press release.

Another encampment in the Deanwood neighborhood underwent a closure on April 13. It sat behind a lot bought by the construction company United General Contractors, which filed a request to D.C. in January to build an apartment building there. DMHHS conducted an immediate disposition on the same spot on May 17.

As for 111 K Street NE, Smith asked city officials on the day of the clearing there what the end result would look like. He fears encampments will continue to form outside the building because residents are not being housed.

“We’re building these multi-million-dollar apartment complexes, but it doesn’t register to say, ‘Hey, can we build a place where [encampment residents] can live and get social services on site?’” Smith said.

In response to a question about concerns that rising encampment closures will make it harder for residents to move into housing, DMHHS said the people being displaced receive outreach services before closures, though several have recently said those services are lacking.

“The intent of our encampment protocol efforts is not to create additional barriers for residents,” Weldon wrote. “We are obligated with the dual responsibility of addressing all health and safety risk factors that pose a negative impact on both housed and unhoused residents.”

Hawkins argued that encampment closures can delay the housing process, especially as residents move to more remote areas. Outreach workers consistently say that encampment closures harm trust and make it harder for people to find housing — or another outdoor space to move to if they are wary of emergency shelters.

“We are at the point where we don’t know where to tell clients to go that is a safe space,” Hawkins said, noting that people are not allowed to sleep in parks, along sidewalks, or on public or private land. “Where can people go?”

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Annemarie Cuccia covers D.C. government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. This joint position was made possible by The Nash Foundation and individual contributors.