Cleveland Park’s iconic Uptown Theater has played host to plenty of movie premieres and Hollywood stars over the years. But Emilio Estevez, famous as a director and for his roles in movies such as “The Breakfast Club” and “The Outsiders,” switched up the script last week when he instead appeared at the Cleveland Park Neighborhood Library on March 26 for an early screening of “The Public.” Estevez wrote, directed, and starred in the film alongside Jena Malone, Alec Baldwin, and Christian Slater. The story is set in a public library in Cincinnati that becomes the site of a peaceful sit-in by homeless patrons when the city is hit with bitterly cold winter storms and all the homeless shelters have reached maximum capacity.

The Cleveland Park event was one of about 30 free screenings held in recent weeks at public libraries across the country. Estevez said he wanted to give the movie wide exposure to the audience he was trying to honor, including librarians and library patrons, before introducing the film to more mainstream media. It will open in theaters nationwide on April 5.

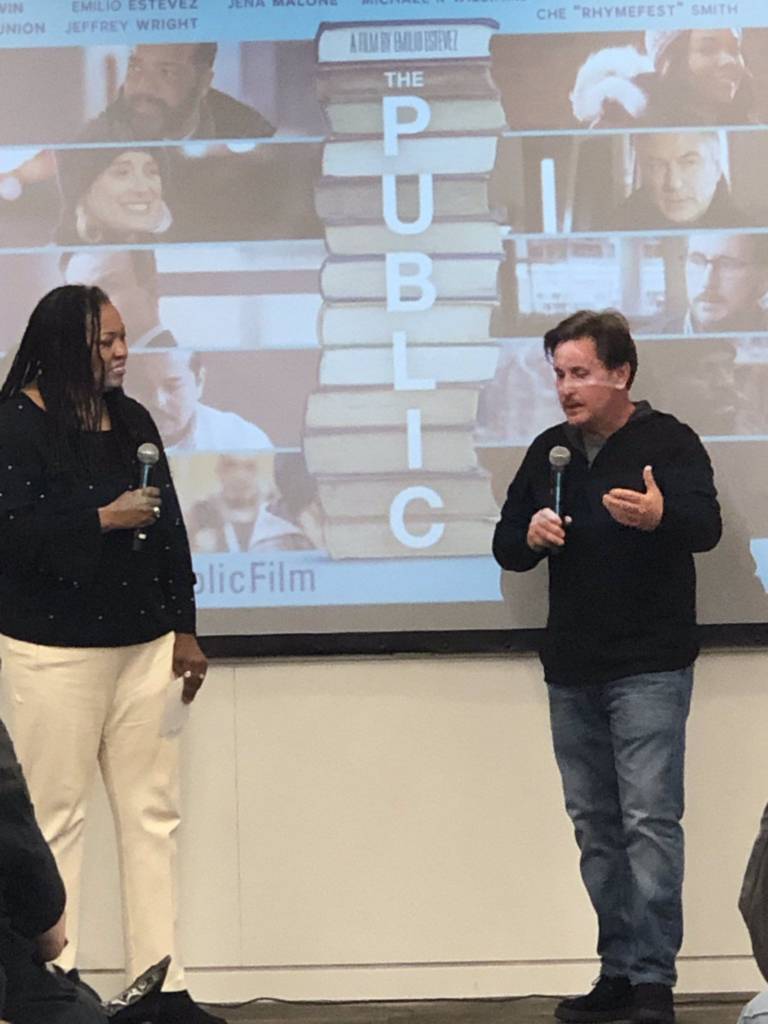

Roughly 200 people packed the library conference room, with audience members, one of them At-Large Councilmember David Grosso, laughing and applauding during the screening. Afterward D.C. Public Library Executive Director Richard Reyes-Gavilan introduced Estevez and Thrive D.C. Executive Director Alicia Horton to discuss the film.

Estevez said he started working on this project around 2007 after reading “Written Off,” a Los Angeles Times article by Chip Ward, the former assistant director of the Salt Lake City Public Library, about his experiences with mentally ill and homeless library patrons. Ward’s descriptions of librarians’ increasingly complicated roles provided Estevez with the starting point for “The Public.”

Making an independent film with a small budget meant balancing the commercial needs of Hollywood, and telling a respectful and authentic tale was on Estevez’s mind throughout filming. He said he worked hard to avoid exploiting poverty and mental illness and peppered his film crew with questions such as “Are we glamorizing this?” and “Are we getting out of our lane?”

Seeking authenticity, Estevez conducted research by spending time in public libraries and talking with patrons and librarians. “It’s that fine line between being a journalist and a vulture,” he said, explaining that he encountered some patrons who disliked his probing so much that they spit on him. Some of the stories he heard were heartbreaking, some hilarious. He attempted to use that humor to humanize the characters in the movie, and to make it more marketable.

“The Public” has thus far been received positively by librarians and homeless viewers alike. It sheds light on the fact that many librarians have become de facto social workers, and dispels the myth that librarians sit and read all day. It also seeks to show viewers the importance of listening to the voices of people experiencing homelessness. According to the Chicago Tribune, one homeless audience member said at a screening, “A lot of people don’t pay attention to what we have to say. Thank you for educating people.”

Estevez wanted “The Public” to be a tool to help viewers “start to check their bias when it comes to people on the street.” He altered the film to decrease its rating from R to PG-13 so that it could be used more easily in schools, libraries, and church groups.

Though it took Estevez about 12 years to bring the project to fruition, he ended up with a sense of urgency to bring the story to the big screen. “Watching the news, I knew this was a movie that had to get finished,” he said. “The longer this movie didn’t get made, the more relevant it became.”

In some ways, “The Public” comes across as a feel-good movie. However, Estevez recognizes that advocacy does not always lead to a Hollywood ending. “We know it doesn’t always end this way. More often than not, it ends violently,” Estevez said.

He drew inspiration for the movie’s depictions of activism from his father Martin Sheen’s own history with advocacy. Sheen was arrested in D.C. alongside activist Mitch Snyder in 1987 after gaining entry to the Farragut West Metrorail station entrance after hours. They were protesting Metro’s refusal to allow people experiencing homelessness to take shelter in the entryway after midnight, according to a Washington Post report. On screen, Sheen narrated the 1988 documentary “Promises to Keep” and starred in the 1986 made-for-TV movie “Samaritan: The Mitch Snyder Story,” both of which follow the efforts of Snyder and the Community for Creative Non-Violence to establish one of the country’s largest shelters, now located at 2nd and D streets NW.

Estevez is hopeful that “The Public” can begin to change the way we think about homelessness. “We need to treat homelessness as a situation, not a condition.”

In the District, the DCPL accepted its role as de facto day shelter with the creation of the Peer Outreach Program in 2014. The program, which is being piloted throughout D.C., trains workers to engage directly with patrons experiencing homelessness. It is funded by the same federal grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration that funds other homeless service providers in the District, including Miriam’s Kitchen, Pathways to Housing, MBI Health Services, and Community Connections.

Jean Badalamenti — the Health and Human Services Coordinator for DCPL who oversees the Peer Outreach Program — was only the second social worker to be employed in a U.S. library when she was hired in 2014. She is responsible for systemwide initiatives to engage homeless patrons at all of DCPL’s branches.

According to Badalamenti, the Peer Outreach Program currently employs three specialists certified by the D.C. Department of Behavioral Health who are responsible for engaging one-on-one with homeless patrons. These workers are “peers” because they have each had past experience with homelessness. They help patrons obtain documentation such as non-driver IDs and birth certificates, direct them to local mental health services, and refer them to substance abuse support systems. The library’s peer workers have even helped place 10 people in permanent or transitional housing.

While the Peer Outreach Program does not document the number of homeless patrons it serves, Badalamenti said that tracking the number of workers’ engagements with homeless patrons helps the program to gauge its success. These interactions can include meeting new patrons, helping them to obtain IDs, connecting them to resources such as shelters, or helping them to receive benefits such as Medicaid. In February alone, the program documented 103 such engagements.

In the future, Badalamenti looks forward to the reopening of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library downtown and hopes to expand both the number of Peer Outreach Program workers and the number of opportunities specifically for homeless patrons. One ongoing program the library offers at multiple branches each month is “Coffee and Conversations,” which provides patrons with coffee and a safe space to socialize and discuss important issues.

Badalamenti was part of the crowd at the Cleveland Park Neighborhood Library that got a sneak peek at “The Public.” “It was definitely a Hollywood movie,” she said with a laugh. Even so, she described Estevez’s portrayal of public libraries as fairly accurate and said she appreciated that he showed the library’s homeless patrons taking agency and standing up for their rights in a peaceful way.

“Libraries have always welcomed people who are experiencing homelessness into their buildings,” Badalamenti said. “We don’t discriminate about who comes in or out.”

She sees DCPL as part of a larger movement of libraries around the country that are beginning to find even more ways to help. According to the Chicago Tribune, there are now at least 30 library systems around the country that employ full-time social workers, including San Francisco, Denver, Chicago, and Brooklyn.

“People are here — let’s meet them here, and let’s help them,” Badalamenti said. “I feel like libraries want to be a part of that.”

This article was co-published with www.TheDCLine.org