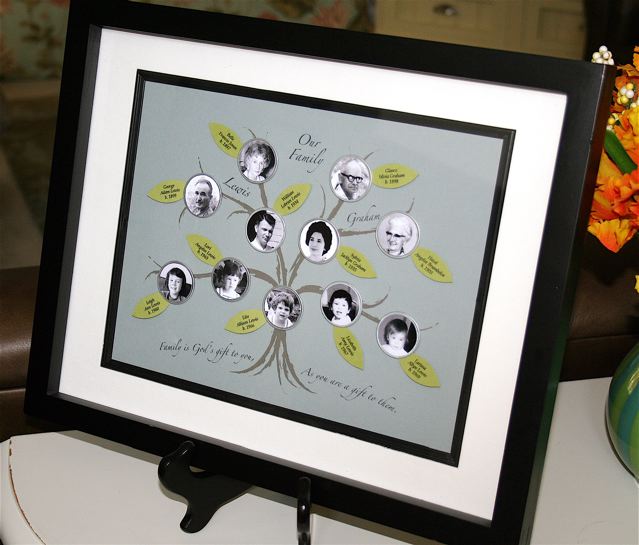

If any one of us researched our extended family tree, chances are we’d discover that members of our family had been homeless. Our homeless family members may not have lived on the street or in a shelter, although often enough they do. Maybe our family spent a few months in our basement. Maybe they camped out for the summer, and no one mentioned that they didn’t have another choice. Maybe you have offered a couch to a young relative for a week or two. There’s a lot of “getting back on our feet” in everyday life. None of us are more than a few degrees of separation away from some expression of American poverty.

The herded masses of unhoused men, or solitary mother and children, are not in a different world from those family members we’ve helped out ourselves. They’re just like your family members–but they lack someone like you helping them. If we saw the unhoused homeless as part of our family too–rather than as incomprehensible strangers–the world would seem a different place in many ways.

When we discover ourselves in those who are without housing, all the regular ways we respond to the homeless change. We reject our tendency to pity those who are downtrodden. We resist ignoring those who we feel deserve their lot in life. We refuse to only focus our generosity upon those who we perceive as ranking higher on some compassion scale. We resist the luxury of running away and hiding from the truth when we feel frightened or overwhelmed.

Given that all indications point to the fact that homelessness won’t be eradicated in our lifetime, perhaps our time would be well spent coming to recognize, know, and understand our homeless brothers and sisters. Maybe building relationships with homeless people is where we’ll find salvation and solutions in the future. Maybe building relationships becomes easier when we think of the homeless as family.

Last week in the New York Times‘ Upshot section Justin Wolfers, David Leonhardt and Kevin Quealy reported that America has “1.5 Million Missing Black Men”, citing crime, health, and prisons. What the researchers failed to detail as a primary cause and destination of “missing” black men is their disturbing overrepresentation in homeless shelters across America. Because we imagine these men as missing and not misplaced, we relieve ourselves of the responsibility to bring these men back from the lost and nameless confines of poverty. But these men aren’t really missing. They are someone’s brother, someone’s son, someone’s cousin. Maybe yours.

There would be a hole in your life if your brother was missing. You would feel sick to your stomach if you couldn’t find your daughter and granddaughter. You wouldn’t be able to turn away. Hiding or ignoring the truth about who we are, individually or as a collective, often has crippling consequences for how we exist in the world. If we see people living in conditions that define the radical nature of poverty and destitution, and choose to ignore them and their causes, we deny a critical part of ourselves, our family, and any beliefs that define us. We choose to deny the very essence of who we are.

Before we can imagine our country free of homelessness, we must first recognize ourselves in all those who live among us unhoused. We must resist the urge to see those in need of our care and love as divisible into deserving, less deserving, and undeserving subpopulations. Our best efforts at preventing, reducing and ending homelessness will only truly begin when we see ourselves as members of the same family.

Neil J. Donovan is CEO of the NJD Group and previously served as president of the National Coalition for the Homeless and as senior advisor to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness.