When Betty Wright left her abusive husband in 1985, she remained homeless for the three years and 10 months that followed.

“I left him and my children, but I had been through the abuse for 30 years. So that’s how long it took me to get strong enough to not be afraid that it didn’t matter what was happening just because I had a roof over my head,” Wright said. “I didn’t feel safe.” At the time, Wright sought out the Bethany House of Northern Virginia, a transitional housing program for female domestic violence victims and their children. To stay longer than the ‘transitional period’ of three months, Wright said she helped manage the house.

“I had been through too many years of abuse that I would not go back unless he changed,” she said.

With the limited resources available in 1985, Wright found another way to get back on her feet: by educating herself. She started taking classes at Northern Virginia Community College.

“One of the classes that I took was a co-op, so I got a 3-credit class for going to work,” Wright recalled. She said her instructors even came to her job and interviewed her employer to see how she was doing. “That was like taking me by the hand and saying ‘I’ll help you through,’ because I had been in the home with children [and] didn’t know if I had any skills.”

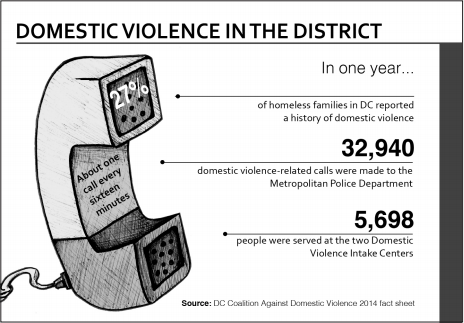

Today, while more resources are available to victims, the challenge of becoming homeless after leaving an abusive relationship remains high, especially locally. Twenty-seven percent of D.C.’s homeless community has experienced domestic violence. For 15 percent of the District’s homeless community, domestic violence was the primary cause of homelessness, according to Carol Loftur-Thun, Interim Executive Director of My Sister’s Place. The nonprofit serves the D.C. area with a free domestic violence hotline, a shelter, referrals to other shelters and a transitional housing program.

“It’s a major change in homelessness here in D.C.,” Loftur-Thun said. “I think it’s very important for our city to understand and start putting the funding and services to align with what has already been identified as a community need.”

While domestic violence has been cited in Mayor Bowser’s 5-year plan to solve homelessness, Loftur-Thun said that only about 2 percent of the funding to address homelessness goes towards helping victims of domestic violence. According to the Metropolitan Police Department in 2014, 32,940 domestic violence-related calls were made to them, with 1 call every 16 minutes. That same year, 5,048 petitions were initiated for Civil Protection Orders, and the two Domestic Violence Intake Center served 5,698 people.

“That’s a pretty big differential: 27 percent versus 2 percent,” she said. “I’d really like to see our city have greater understanding of how domestic violence contributes to homelessness throughout the region.”

Shelters often spark anxiety for women choosing between escaping the danger they know and facing the unknown.

Tenickia Polk knew she had to get out of her abusive relationship but struggled with the housing reality.

“I didn’t really realize that I had become homeless with this decision and I wasn’t familiar with the housing options,” said Polk, another domestic violence survivor. “A shelter sounded pretty scary to me, So what I ended up doing was staying with friends for a very long time, moving from place to place.”

For Polk, financial abuse had taken a toll on her credit. Her husband refused to work for the majority of their marriage and the house and bills were in Tenickia’s name. By the time she left, her bad credit limited her housing options. After going from house to house and staying with her family, she eventually got help from Good Shepherd Housing, a program that helped people with bad credit find housing. “Before the marriage, I had pretty good credit. Good Shepherd Housing was very key. All I needed was an opportunity to build up that credit.”

A big barrier Polk highlighted is that many domestic violence shelters will only house victims for a set period of time. “And that’s unfortunate. I don’t think most people are ready to get off on their own within that time frame,” she said.

Currently, Polk is assisting domestic violence survivors with small emergency housing needs by giving them $200 towards a bill. She gave the first award this weekend to a survivor. She plans to continue soliciting donations for this emergency fund online.

Despite the housing obstacles, Polk still strongly recommends that abuse victims get out. “It’s not worth it. Even when I was homeless, I had more peace of mind. I lost everything – all of my possessions, furniture, all of that, even my car, but those things are replaceable.”

Wright echoed this sentiment and stressed that housing and other forms of material assistance are not the only ways people can help abuse victims. “Encouragement is a powerful tool,” she said.

Victims need someone they can trust to tell them that they can make it, that they have value and that there can be change. Abusers often make victims feel like they have no value and deserve the punishment, according to Wright. “It’s so complicated how you feel about yourself,” she said. “Encouraging survivors to get educated and build their skills lets them know they’re capable.”

Both Wright and Polk agree — it’s hard to build up the courage to get out. Even when you do get out, recovering is always a work in progress.

“Now, I can hold my head up and say that wasn’t me, and that was just my fear holding me captive,” Wright said. “An abuser can do that to people. Somebody that hasn’t been through it couldn’t believe that you could be that fearful of another person.”