D.C. Public Schools reopened limited in-person learning at the beginning of February for the first time in almost a year.

Not all parents, however, are eager to send their children back. And for low-income or housing-insecure parents facing that decision, the ongoing economic crisis leaves them with no good options.

On March 11, 2020, Mayor Muriel Bowser announced a public health emergency amid rising cases of COVID-19, and on March 16, D.C. Public Schools extended its spring break until March 24. Since then, the majority of students in D.C. have attended school remotely until recently, when months of back and forth among parents, D.C. Public Schools, the Office of the State Superintendent, and the Washington Teachers’ Union resulted in an agreement to return. Per a memo from the D.C. Department of General Services, each school will have its own operating plan, including measures to facilitate social distancing, train custodial staff in deep-cleaning protocols, and install improved air filters. There will also be a “situation room” for the DCPS chancellor and the president of the Washington Teachers’ Union to meet and resolve any COVID-related issues.

The operating plan for each school is formed by the school’s Reopen Community Corps. This group is composed of community members, school officials, and members of the Parent- Teachers Association. This group dictates how many days per week students are allowed to attend school in person, along with the length of time each day.

Ayana Osborne, a mother of four children, chose to send two of her children to in-person learning at the start of February. Osborne thought having her children in school would alleviate the pressure and stress but she said, “It’s a waste. They’re there by 8:30 then I gotta be there by 12 o’clock to pick them up. And I have accomplished maybe two things in that time.”

With her two eldest attending school in-person, it remains challenging for her to take care of her youngest child, who was recently evaluated with a mild intellectual disability. “For elementary, none of the special teachers are there in person,” Osborne said. “You have the CARE teachers there, but not the [special education] teachers. So there’s no point in my youngest going to school if the special people to work with her aren’t there.”

According to the DCPS reopening website, “Canvas Academics And Real Engagement” (CARE) classrooms provide online learning for students at school: a quiet space to work, a computer or tablet and headset, breakfast, lunch, and recess. Of the 81 schools listed as providing CARE classrooms, three also have an in-person learning classroom with a volunteer teacher.

Osborne feels unprepared to care for her youngest child’s educational and disability needs because “these things are not being implemented or thought about by the special education population. What things are [DCPS] preparing these parents [with]?” Osborne said. “We don’t have training.”

Nery Peña, a mother of two daughters in a transitional housing program, made the decision to enroll her children in in-person learning. “I do have a worry” about the risk of COVID-19, Peña told Street Sense Media, but ultimately she felt it was better to have her kids physically in school.

“For my youngest, who has an [Individualized Educational Program (IEP)] and development delay, [remote learning] was super hard for her,” said Peña, a teacher within the D.C. Charter School system. “She didn’t like it. She would cry every day. She easily gets distracted, and she didn’t know what was going on.”

Returning to the classroom, Peña felt, would be an improvement over remote learning. “A first and second grader don’t have that help to log in every day,” she said. “I couldn’t give it to them, they’re not gonna do it. They’re not gonna be interested or they’re gonna find it hard or a struggle to log in every day.”

As a low-income parent, Peña took advantage of devices and internet access provided by DCPS. However, the computers created more problems than solutions.

“Once school started [in August], they were given laptops, headphones, and Wi-Fi and some materials, which was awesome,” Peña said. “But I feel as though the computers were a little outdated, so they were giving a lot of technical problems. They were a little more complicated to manage because they were so old.”

[Read more: COVID-19 and crowded spaces: the not-so-easy start of virtual learning for homeless students]

Peña added: “It’s really hard for kids with IEP to have a full virtual day. She really wasn’t connected, and she really fell behind this year.”

Ultimately, this finalized Peña’s decision to enroll her daughter in in-person learning.

“Her going back to school, for her, was super important for me so she can catch up and receive those services she was receiving in school,” Peña said. She is content with her decision to send her children to school. “Now they go have recess outside,” she said. “Sometimes their lunch is outside.”

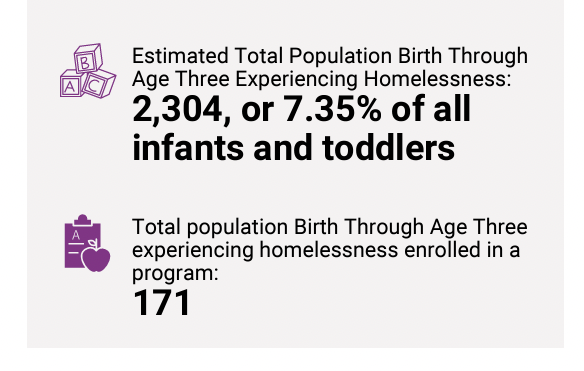

Peña and Osborne are low-income parents who have recently moved into secure housing. But for parents and children experiencing homelessness, the challenges of remote learning have been severe, and the return to school can be a welcome change.

According to DCPS there were 1,892 homeless students registered for school as of Feb. 1, 22% of whom were enrolled in in-person learning. This is consistent with the rate among the broader DCPS student body: About 20% of all DCPS students are enrolled in in-person learning as of now.

Students experiencing housing insecurity or doubling up in households have been among those most affected by the coronavirus pandemic. Before the pandemic, schools provided basic services for many homeless and low-income pupils. Unable to attend school in-person, students were forced to navigate unpredictable circumstances regarding unreliable Wi-Fi and lack of access to laptops. They also struggled with mental health supports and a stable environment for learning.

Case managers have been working closely with parents and children in the city’s family shelters “throughout the COVID-19 pandemic,” the Department of Human Services said in an email to Street Sense Media. “Case managers have an active role in distance learning support for families who may face challenges, and advocate with schools to allow the student to attend in-person learning,” the statement continued. They ensure school-age children are enrolled and have a device, track their attendance, and share parenting and mental health resources with both generations in the family.

Homeless students will be a priority as DCPS moves further towards fully opening schools in the future, according to Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn.

Part of that prioritization will include an expansion of the D.C. State Board of Education’s Office of the Student Advocate, which represents students’ interests. The SBOE has requested funding to increase the office’s staff size to better identify students and families that are at risk and match them with wraparound support services.

Still, one month into D.C.’s experiment with in-person learning, D.C. officials have recognized that the number of students learning in person will likely not increase during the current school year despite falling infection rates and a growing vaccinated population.

The decision of whether to expand in-person learning will ultimately be made by principals, and officials did not mention the implications for homeless students specifically. But all DCPS schools are constrained in their reopening plans by factors like social distancing requirements and caps on class sizes that school leaders are not allowed to override.