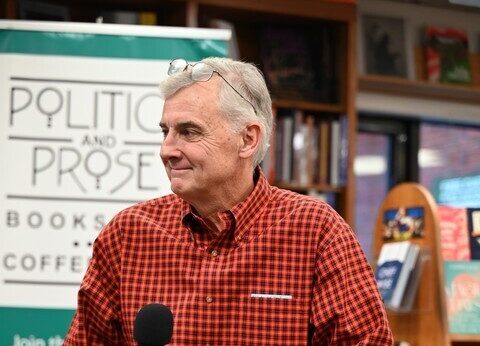

The average person might say the days of elementary school children should be filled with learning, after-school activities, and time to be carefree. However, as a teacher at Lucy Ellen Moten Elementary School in Fort Stanton, Raymond Pyle sees first-hand the harsh realities that some school-age children face growing up in Southeast D.C.

Two of Pyle’s students died recently. One of the deaths was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The other was due to the epidemic of gun violence.

Twenty-one percent more homicides had been committed in the District this year than last as of Aug. 11, according to the Metropolitan Police Department. At this time last year, there had been 98 homicides, while there are already 119 in 2020.

“You see these kids every day and you grow bonds with them, just to watch them become a headline that is lost in time,” Pyle said.

In between lessons, he gives his students words of love and encouragement: “At the end of the day, when you exit the classroom you are my beautiful Black children, and I will do what it takes to see you succeed as if you were my own brothers and sisters.”

[su_pullquote align=”right”]

“You see these kids every day and you grow bonds with them, just to watch them become a headline that is lost in time.”

[/su_pullquote]Pyle, 26, has big plans for each of his students inside and outside of the classroom. But without community support, his dreams cannot become reality.

“They don’t understand that we don’t have funding,” he said. Pyle’s school spends about $5,000 more per student than some schools in wealthier areas. But its students also have much greater needs.

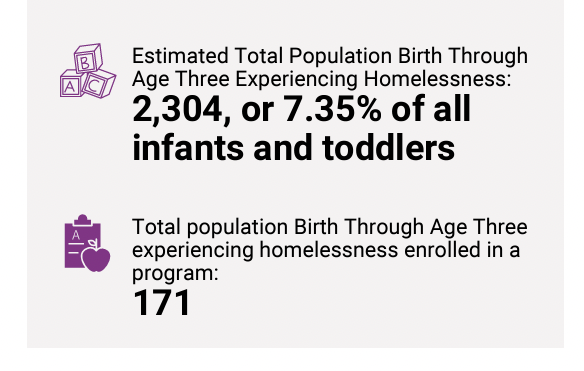

The student body at Moten, located in Ward 8 east of Barry Farm and south of Anacostia, is 97% Black, according to the 2019 D.C. School Report Card. Eighty-three percent of students were considered “at risk” last year, and 8% experienced homelessness. Students receive 90 minutes of physical activity time per week. There is no before-school care, while after school care is available for a fee. There are five Metro buses that can be used to get to the school. Next year’s budget includes $4.9 million to support the school’s 403 students.

The top-rated elementary school in the District for the 2018-19 school year was Janney Elementary, located in wealthy Ward 3, according to School Digger. The website ranks schools based on compiled data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Census Bureau, and the D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

Janney had 748 students in 2019, 72% of whom were white, and 1% of which were considered at risk, according to the D.C. School Report Card. None experienced homelessness. Before-school care is offered with payment on a sliding scale. The same is true for after-school care. There are 13 buses that can be used to access the school, as well as the Tenleytown Metro station.

There were nearly 8,000 homeless students in the District and more than 46,000 at-risk students, who received Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or food stamps, experienced homelessness or were in foster care, or were at least one year older than the expected age for their grade in high school, according to the 2019 D.C. School Report Card.

“A lot of what we want to do, we don’t have the money for,” Pyle said.

Currently, he and a colleague are putting together a grant application to bring a community garden to a yet-to-be-determined school. Other local programs, like the National Children’s Center, have found community gardens to be a strong addition to early education. Finding financial support for such a garden might seem like a straightforward task, but the idea has gotten lots of pushback. “That’s the hardest thing to get started because no one wants to give it a second thought,” Pyle said.

Ultimately, his goal as an educator is to equip students with the knowledge and skills they need to thrive so that one day they can give back to their communities. “I will volunteer my time to make sure that these kids succeed because, at the end of the day, I had teachers that did that for me, and they didn’t have to do that,” he said.

Feeling worlds apart

Growing up in two different cities allowed Pyle to experience different cultures at a young age. From kindergarten through fourth grade, he lived in Brooklyn, New York. He spent the rest of his school years in New Jersey. For Pyle, Brooklyn offered more access to people from all walks of life, while educational settings in New Jersey were more racially divided. The transition between the two cities was not easy.

“Imagine everyone looking like you, talking like you, sounding like you, and then you go to a completely new area where you’re kinda on your own; it’s a shock,” Pyle said. This experience is a reason he wants to ensure that students from all backgrounds are given new experiences and equal learning opportunities.

“You get a whole different perspective because you’re so used to one group of people your whole life,” he said. “Seeing someone new and experiencing something new is important and that’s what I try to bring into the classroom.”

Pyle believes the problems he dealt with growing up are still present in the country’s education system and that turning things around starts with addressing a disconnect between lawmakers and those working directly in schools.

He said lawmakers should be held accountable for how their decisions affect students. He wants more local leaders to visit classrooms. “Is it the community itself or is it the people outside of the community consistently not providing the resources and listening to our voices?” he said.

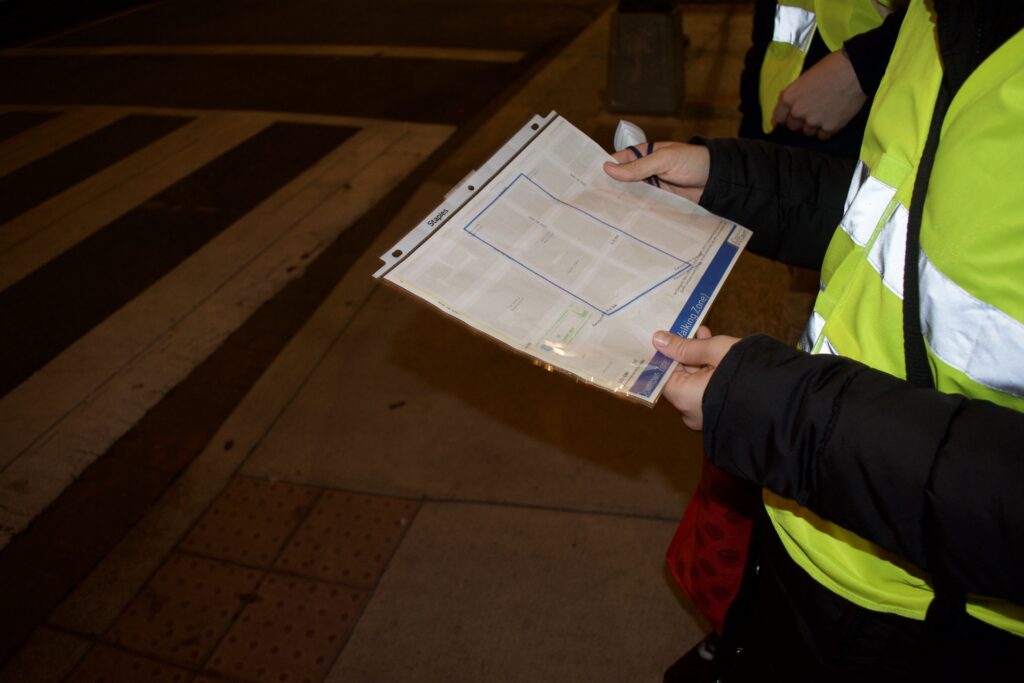

[Read more: In June, Pyle participated in a sit-in across from the Wilson Building]

The OSSE wanted 65% of low-performing schools to show growth in academic achievement during fiscal year 2019, according to information submitted to the D.C. Council during the last budget cycle. The school system surpassed that goal and 80% of low-performing schools improved their rankings; the goal set for fiscal year 2020 is another year of 80% improvement.

A foundation for education

Pyle is part of the Urban Teachers program, which places teachers in urban schools in Baltimore, D.C., and Dallas, and keeps them there, as a means of addressing structural racism. D.C. has a 25% rate of attrition for its public school teachers, 10% higher than the national average. A report published in March by the D.C. State Board of Education found that most teachers who left voluntarily did so during the first three years, even though they had planned to stay for a decade or more.

While in the Urban Teachers program, educators go through three years of intensive training. They leave the program with a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University and dual certification in special education and elementary education, secondary math, or secondary English, according to the program’s website. Urban Teachers placed Pyle at Moten in the fall of 2019. He started teaching fourth grade but moved to first grade when the first-grade teacher left.

“We have a lot of young, passionate teachers who just want the opportunity and the space to do this,” he said of the program.

In the upcoming school year, Pyle will teach pre-kindergarten. He hopes to give students the tools and space they need to grow while also helping them find their purpose in life.

Pyle wants people to recognize that teachers reach into their own pockets to help students, but their money can only go far. He wants elected officials to accept that educational environments must change and grow; the environment must empower teachers to address every student’s needs.

“You know the societies that lasted the longest survived because they put back into their school systems, and those people become educated, passed on their knowledge, created something new, and then you have a cycle,” Pyle said.