By law, food served in D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) must be of high nutritional value. Over the years, federal and local government agencies have passed legislation like the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010, and the D.C. Healthy Schools Act and Amendment to ensure well-fed, well-nourished and, in turn, well-educated children.

But despite DCPS’s stated commitment to maintaining high nutritional standards, D.C. students remain unhappy and underserved, according to students and adult advocate testimony at a Sept. 6 hearing, and reports across prior years.

Now, as concerns with DCPS food service delivery contracts come to light, several students, families and D.C. advocates are eager to seize the opportunity and improve both transparency and competency within the DCPS system, and child satisfaction with school food.

Long before recent controversy, criticism ran rampant in D.C. concerning contracting and food service practices in public schools.

In April 2015, during a DCPS Budget Oversight Hearing, observers called D.C. school food disgusting. At the time, the Huffington Post published a report by a student that described the food served by then-provider Chartwells as not fresh and unsanitary.

The hearing also established that DCPS’s outsourcing of food service programs resulted in the loss of millions of dollars annually. Due to contracting errors, the city lost money on every meal it served.

This May, concerns appeared once more.

DCPS paid dozens of service contracts without the required D.C. Council approval, the school system disclosed this spring. The news sparked outrage among councilmembers, especially Council Chair Phil Mendelson. Staffers involved in this scandal were disciplined, according to DCPS, and the Office of the Inspector General launched an investigation into the contracts. But the discovery of contractual misconduct is illuminating long-standing complaints about food service and food quality.

Student dissatisfaction with school food can come from a few places. There’s a prevalent belief that students complain because they want food like chicken nuggets and pizza as opposed to healthier foods. But students and families report this isn’t the issue in D.C. While DCPS proudly holds some of the highest nutrition standards in the country and is committed to providing nourishing meals for their students, in recent years, students say the food served has been substandard and non-nutritious.

Ydidiya Nadew is a student at Columbia Heights Educational Campus (CHEC). In June 2022, students were surveyed about their cafeteria experience there. According to an Urban Institute report on the survey, 61% reported being unsatisfied with school offerings. In Nadew’s tesyimony, even after his food service provider worked on improvements, the food doesn’t “taste good” and the offerings are “not very enjoyable.”

In a Sept. 6 Committee of the Whole Public Roundtable hearing on the matter of food service, Nadew testified that a huge downfall of the current school food provisions is that they are not culturally considerate. Every student comes from a different background and has their own diverse palate that, according to him, the current systems do not accommodate. Nadew was the only student to testify at the hearing, but says his concerns are echoed by others — he worked with four other students and the Urban Institute to collect student feedback on school food.

Councilmembers seemed to take students’ feedback to heart.

“We know that there is a high correlation between students’ ability to learn and the quality of food that they get,” Mendelson said during the hearing. It is “important for both educational purposes as well as the quality of life for some students.”

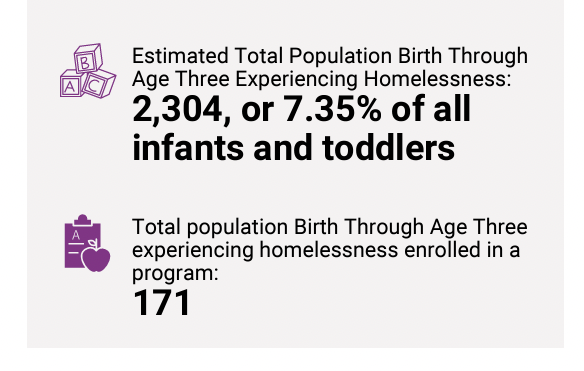

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 77% of D.C.’s children relied on free or reduced-cost meals provided by DCPS to cover their daily nutritional needs. School-provided meals go a long way toward preventing hunger in D.C. children and hunger for children in the United States at large, according to a report by D.C. Hunger Solutions.

Since 2016, DCPS has exclusively partnered with SodexoMagic and D.C. Central Kitchen, to serve school food. That’s the last time DCPS sought food service contracts through a competitive bidding process.

DCPS is set to provide new food service contracts to the council by November and implement them in early 2024, which will effectively end the current reliance on bridge contracts with SodexoMagic and D.C. Central Kitchen that are in place due to the delays. The bidding process will allow for other contracts to be presented to the council, too.

DCPS blames current contract delays on the Office of the Attorney General, who must review food service contracts to make sure they meet legal standards — especially given prior contracting malpractice.

While food service providers like D.C. Central Kitchen worry the new contracts will disrupt the physical food service at school if providers change drastically, DCPS hopes to provide a seamless transition, said Patrick Ashley, chief of fiscal strategy for DCPS.

But the issue may not be resolved in November, according to Alexander More, chief development officer at D.C. Central Kitchen. He hopes the District rexamines DCPS contracting practices. He’s hoping to see more inclusive procurement processes and clearer communication while the processes are underway, along with coordination between the approval of a contract and the first day of food service under said contract, he said at the September hearing.

Kenneth Mackie Jr., operations director of RunVeggie, a local D.C. food service, noted in the Sept. 6 hearing that if DCPS expanded the contracting opportunities to local businesses, they might be able to cater to students’ different palettes. This practice might serve to better address student dissatisfaction with meals provided to them, he suggested, as focus groups and improvement efforts by large providers like SodexoMagic (in collaboration with schools) have only been mildly effective.

“The current structure of DCPS food service contracts is misaligned with the goals and values of the District of Columbia, particularly those related to economic development and community wellbeing,” Mackie said in his testimony.