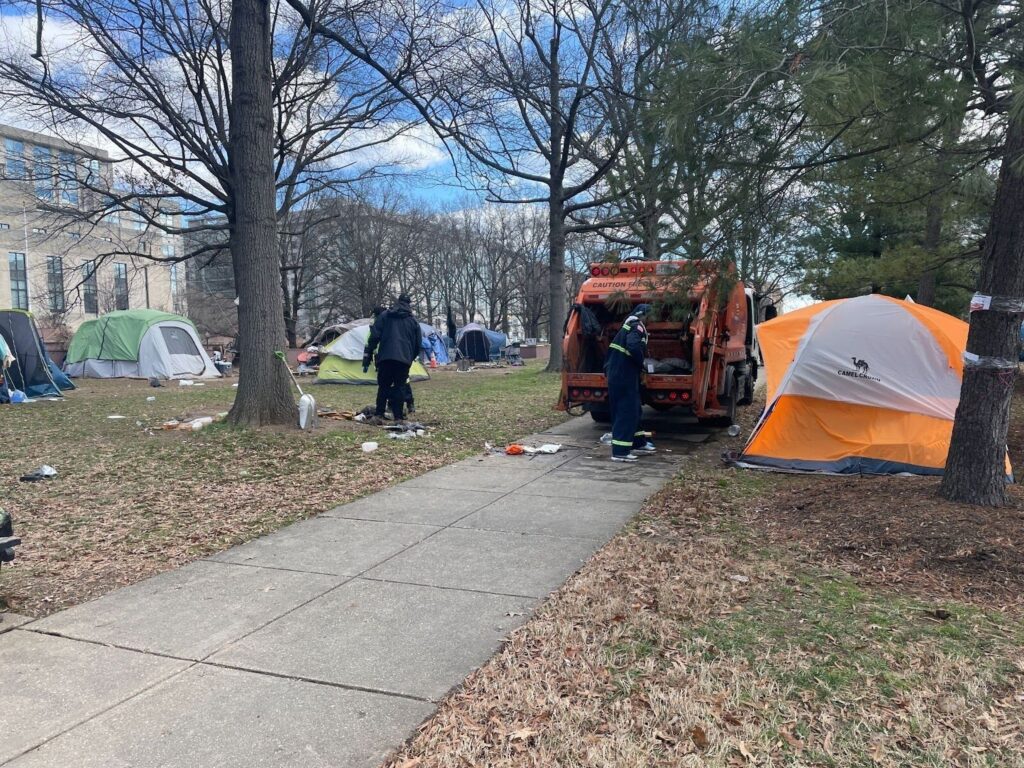

Getachew Gurumu became homeless for the first time after he received an eviction notice from his landlord during the pandemic. Then, without warning, he lost his job. Unsure what to do or where to go, Gurumu moved to McPherson Square in the summer of 2020. Three years later, the National Park Service permanently closed the encampment, forcing Gurumu and many others to find a new place to live. Gurumu is now trying to find a lawyer in hopes of getting compensation for the eviction, which occurred during the nationwide eviction moratorium.

When the pandemic began, homeless service providers across the nation worried that stories like Gurumu’s would become common and that as lost jobs butted up against unpaid rent, there would be an increase in homelessness. But the federal moratorium and an inflow of rental and unemployment benefits seemed to help prevent that, so much so that annual surveys in 2021 and 2022 found that homelessness in D.C. decreased.

Not anymore. For the first time since 2016, more people in D.C. are experiencing homelessness this year than in the prior year, according to the 2023 Point-in-Time (PIT) Count results, released in early May. This year’s PIT Count reported 389 families and 3,750 individuals were experiencing homelessness, compared with 344 families and 3,403 individuals in 2022.

The results, which homeless service providers say are disturbing but not surprising, come as the D.C. Council prepares to finalize the city’s budget for fiscal year 2024. The current budget proposal, put forward by Council Chair Phil Mendelson and approved May 16 on first reading by the council, authorizes 230 new housing vouchers for people experiencing homelessness and maintains funds for eviction prevention, two programs legislators say are key to preventing homelessness from rising further. Mendelson’s proposal is a step in the right direction, advocates say — the mayor initially cut eviction prevention funds and included no new vouchers — but would still mean fewer resources are available than in 2023.

The PIT Count’s imperfections

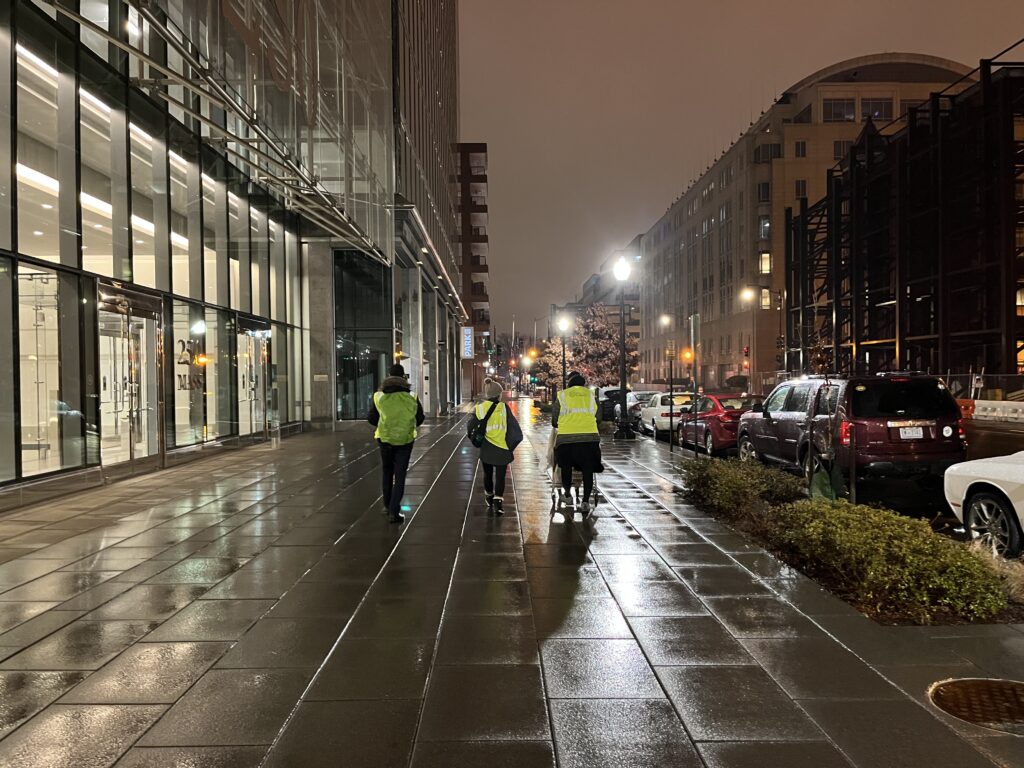

The PIT Count is a federally mandated annual census of the nation’s homeless population. Every January, a mix of social workers and volunteers do their best to count all of the people sleeping in shelters, transitional housing programs and outdoors on one of the coldest nights of the year. This count is meant to be used to help inform jurisdictions about the local demand for affordable housing and homeless services.

But the result is nearly always an undercount, said Amber Harding, executive director of the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless.

While the PIT Count receives the most attention as the official measurement of homelessness in a given jurisdiction, it is imperfect and not the only metric available in D.C. For instance, every year the District government tracks the number of people who use its homeless services system. It is generally double or triple the number seen at the PIT Count — throughout fiscal year 2022, 1,037 families and 7,834 individuals asked for help through the local homeless services system.

Since the PIT Count by definition represents a single point in time, it’s almost certain to be less than the number of people who experience homelessness over a year. But experts say the PIT Count also misses some housing-insecure people, such as those who are couch surfing, squatting or otherwise not visibly homeless, and thus not counted by outreach workers. And since the yearly count is held in January, when the weather is cold in much of the country, people who don’t have a reliable place to sleep may use limited resources on the night of the count to stay with a friend or get a hotel room, rendering them invisible.

This can especially lead to an undercount of families, Harding said. Parents often fear they will lose custody of their kids if they are found sleeping on the street, so they are more likely to couch surf or stay somewhere that is hard to find, like a laundromat, basement or abandoned building. Many families in the District also rely on Rapid Rehousing, which is essentially a form of transitional housing but is not included in the PIT Count.

Other methods of measuring homelessness also suggest the PIT Count is missing people. The D.C. Public Schools system relies on self-identification and homeless liaisons to identify students experiencing homelessness. According to its count as analyzed by Schoolhouse Connection, about three-quarters of students who said they were homeless from 2020 to 2021 were not staying at a shelter but instead staying with another family. This discrepancy suggests up to 3,760 children could have been missed in the PIT Count since it relies largely on reports from shelters to measure family homelessness. School estimates also include all families experiencing homelessness across a school year, rather than on one night.

Gaining an accurate measure of homelessness in the District is also complicated by distinctions in the official definitions. For instance, in D.C., unhoused migrant families who arrived via buses in the last year are legally not considered homeless, though they have no place to go. In January and February, between 800 and 1,000 unhoused migrants lived in hotel rooms the local government provided them, but were not included in the PIT Count, according to presentations from the Office of Migrant Services.

Homelessness in D.C., according to the PIT Count

This year’s PIT Count, held on Jan. 25, found 4,922 people were experiencing homelessness, 512 more people than in the 2022 count. Half of those people were experiencing homelessness for the first time, and 825 were living outside.

Of those 4,922 people, 3,750 are single individuals and the other 1,172 are experiencing homelessness with their families. Family homelessness is up from last year, but still significantly lower than in 2016. Individual homelessness, however, is higher this year than it was in 2016. Overall, D.C. saw a 12% increase in homelessness from the previous year, but a 23% decrease since 2020, the city’s most recent pre-pandemic PIT Count.

A disproportionate number of people counted in the PIT Count are Black, Asian or Indigenous, making up 88% of those counted but just 54% of D.C.’s population — a disparity attributable to structural inequities that have prevented Black people in particular from building and keeping wealth in America. Women make up about a third of the population experiencing homelessness, an increase from past years.

D.C.’s homeless population is also susceptible to health risks, the PIT Count shows. Seniors made up a third of the individual adult homeless population. Thirty-nine percent of the individuals counted were experiencing chronic homelessness, which means they have a disabling condition and have been homeless for at least a year or on three separate occasions over a few years.

D.C. is not alone in reporting more people experiencing homelessness. Across the metropolitan area, homelessness increased by 18%, or 1,339 people. While D.C. has the most people experiencing homelessness, surrounding counties saw higher increases, such as 122% in Loudoun County and 54% in Montgomery County.

In announcing D.C.’s results, the Department of Human Services emphasized the significance of the overall decrease in homelessness over the past three years. But many advocates and providers saw this year’s increase as a dire warning sign that D.C.’s progress so far on reducing homelessness is fragile. For that progress to continue, the city needs to meet the new demand, providers said.

“This kind of a jump becomes so concerning,” said Christy Respress, the CEO of Pathways to Housing. “If we’re not continuing to make those investments … then we’re just going to see these numbers rise and rise.”

Most of the people counted in 2023 were living in a shelter or a transitional housing program, such as the Pandemic Emergency Program for Medically Vulnerable Individuals (PEP-V), which is set to close by October. But the number of single adults living outside increased by 19% compared with last year, despite multiple encampment closures in 2022. Many encampment residents have told Street Sense reporters that they prefer the flexibility and autonomy of encampments to the rules — and sometimes poor conditions and abuse — they encounter at shelters.

What drove the increase?

Local homelessness service providers generally attribute the increase to a combination of factors — including the pandemic, evictions and rising housing costs.

District residents facing homelessness during the pandemic had an array of helpful if patchy resources. No one could be evicted, and renters who were behind on rent could rely on programs such as STAY DC and the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). This means D.C.’s social safety net was likely helping people stay housed, as opposed to helping them via the homeless services system, according to a report from The Community Partnership at an Interagency Council on Homelessness meeting in early May. The Community Partnership administers the PIT Count and coordinates parts of the city’s homeless services system.

Many providers characterized the increase this year as a delayed consequence of the pandemic. Eviction resources and program extensions kept many people housed through 2022, and others may have found temporary solutions, such as couch surfing — delaying their entry into the homeless services system.

“A lot of homelessness in this city is people who were barely hanging on for a long time,” Harding said.

That could explain why the share of people newly experiencing homelessness increased for the first time in 2022 and 2023. In the past, people new to homelessness accounted for about 30% of the population, but in 2023, that share reached 50%. As rental assistance resources wound down, and evictions in D.C. picked up, it’s likely more people found themselves without stable housing.

The pandemic also led to increased domestic violence, a leading cause of homelessness for women and families. In 2023, 24% of the individuals surveyed and 55% of the families had experienced domestic violence, and over half said that experience had directly caused their homelessness.

Calvary Women’s Services has seen more demand over the last year, largely driven by an increase in women leaving unsafe situations, according to Kris Thompson, the group’s CEO. Calvary has added 24 new spots in its housing programs in an effort to meet the need.

Finally, there’s the ever-rising cost of living in the District. Rents have risen over the past year even as benefits from many social safety net programs have decreased. Meanwhile, wages have frequently not kept pace, meaning more households are paying a large portion of their income to rent, an early predictor of homelessness.

“Affordable housing in this city is just, it just feels nonexistent,” Thompson said. “Rent increases have just outstripped any ability for people to keep up.”

Enough money to end homelessness

After Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration adopted Homeward D.C. in 2016, the District began seeing reductions in the number of families experiencing homelessness year after year. D.C. officials have attributed the drop to the influx of resources such as new shelters and housing programs. But the District only began making similar investments for individuals a few years ago, as Interagency Council on Homelessness Director Theresa Silla said at a D.C. Council oversight hearing.

The good news in this year’s PIT Count, advocates say, is that there’s a strong indication the money D.C. has put toward ending homelessness is working: The number of people who were able to exit homelessness increased by 57% last year. But the very resources advocates touted as successful so far — and necessary to prevent another rise in homelessness in 2024 — are the ones the mayor proposed cutting in this year’s budget.

“If we’re seeing an increase of over 10% in the number of people experiencing homelessness, obviously this isn’t the moment to lose more resources,” Thompson said.

The budget given initial approval on May 16 by the D.C. Council includes more spending for eviction prevention and vouchers, two of the major asks of the Way Home Campaign, which seeks to end homelessness in the District. But the proposed funding, for vouchers especially, is still below what some advocates say is needed to see a decrease in homelessness.

D.C.’s ERAP — which can pay missed rent, helping residents avoid eviction — originally faced a budget cut of over $30 million, but Council Chair Mendelson proposed to reverse the cut. While ERAP is not as expansive as the federal eviction prevention programs in place at the height of the pandemic, many D.C. residents have credited it with keeping them out of homelessness.

The program is currently set to have $43 million in fiscal year 2024. This year, that amount of money enabled the city to help residents for only five months, prompting advocates to recommend $117 million for 2024 in hopes it would last the year. Even with this year’s funding for ERAP, they note, many people became homeless for the first time through evictions.

Under Mendelson’s proposal, D.C. is set to fund just 230 new Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) vouchers, which have been key to moving people out of homelessness, compared to over 1,000 vouchers in past years. That’s an increase from the mayor’s proposal of no new vouchers, but the Way Home Campaign is asking the council to fund about 1,700 total new vouchers before it finalizes the budget. While the city has faced challenges in implementing the existing vouchers, service providers say the program is improving and the backlog will soon ease.

Mendelson’s budget proposal also reverses many of the cuts homeless service providers spoke out against, including money for legal assistance to help tenants fight eviction cases and for domestic violence services.

The council will have to officially approve the budget on May 30 with a second vote.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Annemarie Cuccia covers D.C. government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. This joint position was made possible by The Nash Foundation and individual contributors.