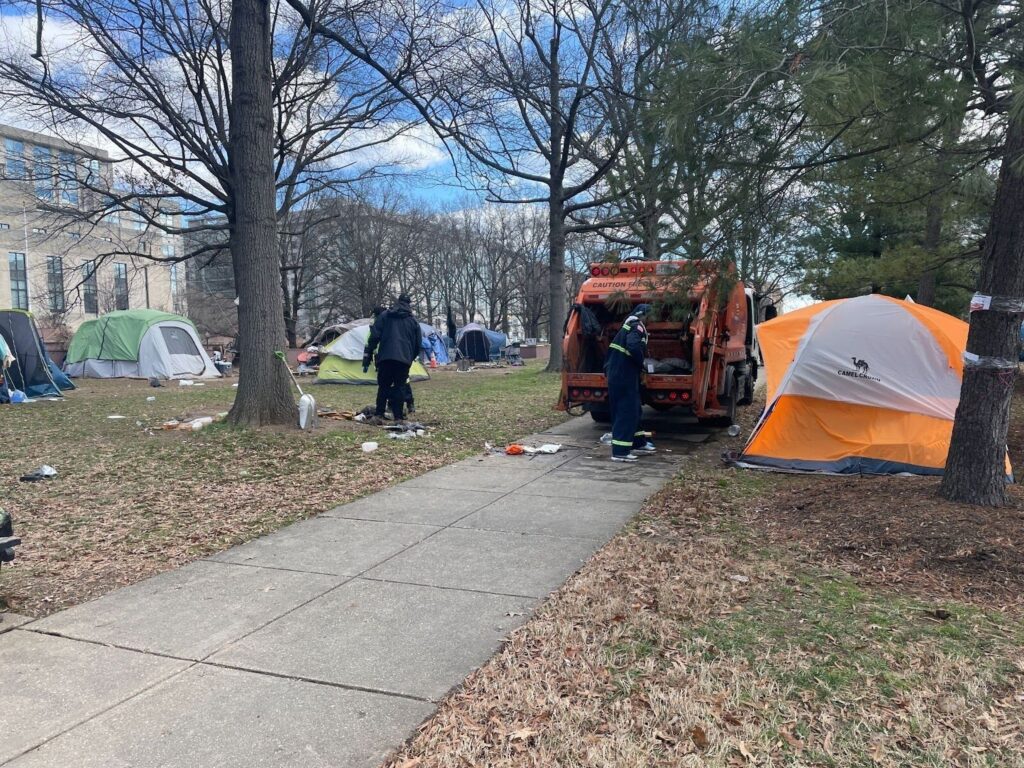

D.C. is relying on immediate dispositions to close encampments at high rates, officials testified at a Feb. 8 oversight hearing for the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS). Legal advocates are pushing back on the policy, which they say allows the city to close encampments with little to no notice.

In fiscal year 2023, 50% of the 82 encampment engagements conducted by DMHHS were immediate dispositions, Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Wayne Turnage testified at the oversight hearing before the D.C. Council Health Committee.

A 2023 census of encampments recorded 210 unhoused individuals living outside, 194 tents or structures and 100 encampment sites across the District, according to Turnage. Seven of these sites seemed to be new, he said, while 13 have become inactive. Ward 2 hosts 20% of all city encampments, which is by far the greatest concentration of any ward.

DMHHS closes or ortherwise engages with an encampment whenever a site poses a health, security or safety risk or interferes with community use of public space, according to Turnage. For years, most encampment closures have been standard dispositions, which typically provide residents with 14 days’ notice to move their encampment or any property they wish to keep once the site is closed. Emergencies that pose an imminent threat to the health and safety of the general population trigger an immediate disposition, for which DMHHS is not obligated to provide any prior notice.

According to D.C.’s encampment protocol, immediate dispositions can be justified due to emergency, security, health and safety risks. However, the protocol does not include specific examples of when immediate dispositions are allowed, leaving it to the discretion of DMHHS.

Ann Marie Staudenmaier, senior counsel at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said immediate dispositions have drastically increased in recent years, occurring at an unprecedented rate. In June, Street Sense reported D.C. conducted 59 immediate dispositions in calendar year 2022, the most reported in recent years. (Calendar year 2022, included four months of fiscal year 2023).

“This is significantly more than ever. I’ve never seen them do a lot of immediate dispositions, and 41 is a lot,” Staudenmaier said in an interview with Street Sense.

Frequent immediate dispositions exacerbate the city’s struggle to house residents, Staudenmaier argued. When encampments are cleared with little warning, individuals can lose belongings and documentation needed when applying for housing. In the aftermath of an immediate disposition, it is more difficult for unhoused residents to stay in contact with case managers, she said.

In the past, DMHHS officials have said the rise in immediate dispositions is due to an increase in public health and safety concerns at encampments. But Staudenmaier, who helped write D.C.’s encampment protocol, argued that immediate dispositions were intended to be enacted rarely and in extreme cases of threats to public health and safety. She believes the protocol is best applied if immediate dispositions are conducted only when an encampment can be reasonably considered a danger, not just to residents, but to others in the surrounding area, such as presence of a gun or hazardous substance. None of the 41 immediate dispositions over the last year qualified as a true risk to public health and safety, according to Staudenmaier, who reviewed a list of the justifications.

Street Sense reviewed a similar list in June. While D.C. closed some encampments due to fire hazards or criminal activity according to DMHHS, the most common reasons the city gave for an immediate disposition were that an encampment was blocking a pedestrian passageway or on private land, abandoned property or city parkland. Staudenmaier said for years these types of violations have been considered as justification for standard dispositions, enabling unhoused residents to prepare for a clearing.

“I think that they are violating the letter and the spirit of the protocol that governs how they are supposed to be doing clearings generally,” Staudenmaier said.

Joshua Drumming, a law graduate at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, testified at the hearing encampment closures can harm the health and wellbeing of unhoused residents, retraumatizing an already vulnerable population.

“Many encampment residents are surrounded by every belonging they own, including sentimental things to legal documentation,” Drumming testified. “Some leave their encampment for an hour or two, and upon their return, their home is lost forever.”

Despite no official requirement for notice, Turnage told councilmembers that DMHHS has attempted to give a 24-hour notice for immediate dispositions when possible.

With no notices posted online, immediate dispositions often fly under the radar of the general public and are difficult for advocates to consistently monitor, according to Staudenmaier. She suggested the city create a protocol that explicitly lists the requirements for an immediate disposition.

At the hearing, Turnage also highlighted the findings of a December 2023 follow-up on the Coordinated Assistance and Resources for Encampments (CARE) Pilot Program. First enacted in September 2021, the CARE pilot closed four encampments on city land with the promise of matching the affected residents with housing. Turnage announced that all of the 139 total residents on the official pilot list now have leased apartments, and expressed interest in expanding the program citywide when feasible.

While all of the individuals on CARE’s official list have been housed, Staudenmaier said there were many more unhoused people displaced by the program’s encampment clearings who were not included on the list.

“Everybody else who was in those large encampments has not been housed, and their lives were made more difficult, more precarious because of these huge encampment sweeps that came along with the CARE pilot,” Staudenmaier said.

“Encampment clearings don’t solve homelessness. They don’t make homelessness go away. They make it worse.”