The D.C. Council voted on April 20 to advance the latest revision of the Comprehensive Plan amendment, amid confusion over the scope of the document’s influence and concern among councilmembers that it would reinforce racial inequity in housing in the District.

The Comprehensive Plan is D.C.’s largest planning document that guides the development of housing in the District. First created in 2006, it was designed to be rewritten every 20 years and was first amended in 2011. Citing concerns about increasing housing production in the city to match its growing population, Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office began amending the plan once more in May 2016, extending the document to a lengthy 1,500 pages.

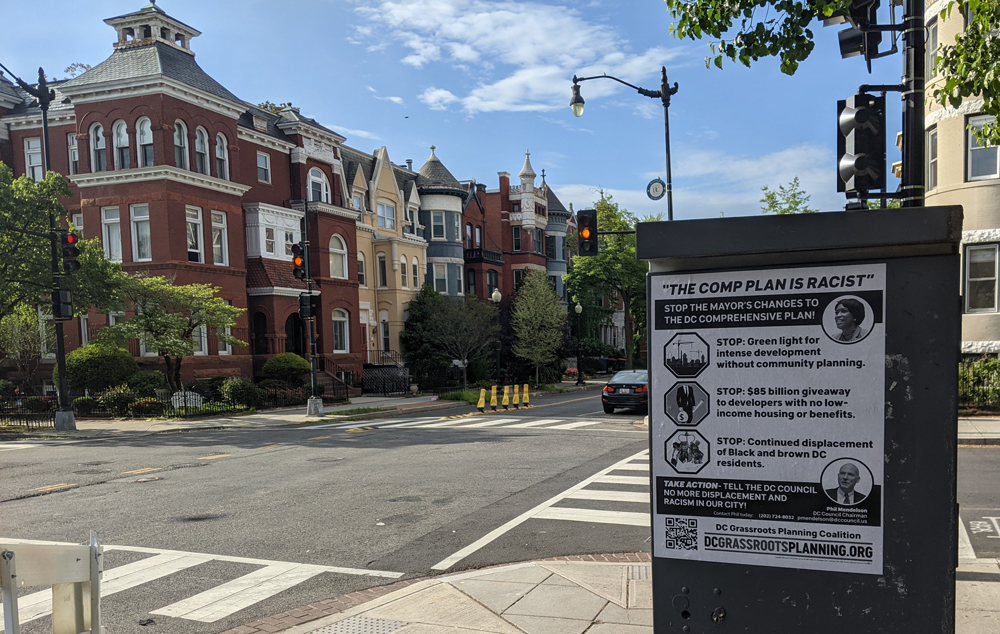

An outpouring of public comments and grassroots campaigns delayed the amendments for nearly five years and led to many revisions, mostly focused on the plan’s impact on the displacement of Black and brown residents. D.C. Council is set to vote on the Comprehensive Plan Amendment Act of 2021 on May 4.

[Read more: An amendment 4 years in the making, with massive implications for affordable housing in DC, to be voted on in March]

The Committee of the Whole meeting on April 20 served as a “markup session” where councilmembers could ask for clarifications and express further changes they would like to see in the amendment before the official first reading. Leading up to that meeting, Council Chair Phil Mendelson shared publicly the “committee print” of the bill — a version that highlights all new changes — that he is required to circulate to all councilmembers since he is introducing the amendments on behalf of the mayor.

The committee print included new language designed to create more affordable housing and to consider the impact of development on Black and brown communities in the District. It addresses several prominent concerns raised in testimonies from 140 D.C. residents and numerous nonprofit advocates during a two-day hearing in November. But even as the amendment advances to a vote, councilmembers, the mayor’s office, and advocates are debating whether it goes far enough to stop displacement.

While the council voted 11-0 to advance the draft from the markup session, At-large Councilmember Elissa Silverman and Ward 4 Councilmember Janeese Lewis George abstained. They cited a racial equity impact assessment published on April 19 by the newly-established Council Office of Racial Equity (CORE). The office’s director, Brian McClure, determined that the amendments bring significant changes to addressing historic racial inequities in housing in the District but “the Plan’s sheer size reduces the impact of the Committee Print’s positive changes.”

“I rarely do this,” Silverman said of her choice not to vote for or against the legislation at this time. “But I cannot vote ‘yes’ until I truly understand what is in this immense document.”

What does the plan do?

The CORE assessment determined that the Comprehensive Plan amendment as written will uphold racial inequity in the District.

“We cannot afford to preserve a status quo that has been displacing thousands of Black and brown D.C. families,” Lewis George said. At least 20,000 Black people were pushed out of the city between 2000 – 2013, according to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

George specifically pointed to the hotly debated Section 500.5c as a potential cause of displacement, which defines what qualifies as “affordable housing.”

The committee print clarified this definition so all mentions of affordable housing in the plan refer to units for households earning 80% or less of D.C.’s Median Family Income — an upper limit of $100,800 for a family of four and $70,550 for a single person.

This update narrowed the range of who “affordable housing” guided by the plan could be built for, with the mayor’s previous version including households that earn up to 120% of the MFI. But many advocates say there is still not enough focus specifically on households that earn 30% or below of the MFI, which are more often families of color. The Census Bureau’s 2015 American Community Survey found that African American households in D.C. had a median income of $41,000, while white households had a median income of $120,000.

Silverman and Lewis George are not alone. Most of the councilmembers who voted “yes” said they were grateful for the increase in racially equitable language in the committee print but still wanted more dramatic changes to break the status quo.

There was also some confusion near the end of the markup over how much control the Comprehensive Plan exerts over development in the District. At-large Councilmember Christina Henderson asked whether the CORE assessment considered a complete rewrite of the Comprehensive Plan to achieve racial equity, to which Mendelson said the Comprehensive Plan is ultimately just a guiding document, and does not actually implement as much change as legislation would.

Discussion ensued between Henderson, Silverman, and Mendelson on how exactly the Comprehensive Plan affects development in the District. When Silverman said the Plan determines how land may be used, Mendelson said it only “generally determines” what may be built and where.

The Comprehensive Plan itself is not a policy or a law that can be enforced. It speaks very generally about what development the government would like to see in the District. However, the D.C. Home Rule Act — the federal legislation that grants the District limited self-government through the mayor and council — stipulates that development in the District must be “not inconsistent” with the Comprehensive Plan. This means that the D.C. Zoning Commission can only approve developments that exceed zoning laws, like high-rise apartment buildings in single family home areas, if they are consistent with the Comprehensive Plan.

“I think it is really clear that all of the councilmembers are confused and unsure about not just the Comp Plan, but land use in general,” said Parisa Norouzi, the founder and director of Empower D.C. and a steering committee member of the D.C. Grassroots Planning Coalition, which has been organizing D.C. residents to comment on the plan and lobby councilmembers for specific changes.

Continued advocacy from opposing sides

The Grassroots Planning Coalition was formed in 2017 by Empower D.C., several ANC representatives, the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, and other organizations. Since then they have consistently advocated for more definitive language in the plan to increase community input in housing developments in the District, to ask developers to create more “deeply affordable housing” for households with incomes at 0-30% of the MFI, and to address racial inequities in housing access and location.

Norouzi and other Grassroots Planning Coalition members held a briefing the day before the markup session to commend the committee print for adding a significant portion of their advocacy to the language. But they said there are still a wealth of changes to be made before the vote.

“One of our top priorities [now] is just making sure that communities have the leverage to negotiate community benefit agreements that are binding and enforceable,” Norouzi said.

A community benefits agreement is a contract signed by a developer and a community the developer seeks to build in. In the contract, the developer agrees to provide community benefits and in turn, the community will agree to not oppose the project.

The coalition has long advocated against some of the mayor’s amendments to the plan that relaxed or entirely removed language around public involvement in development projects in their community. Major concern centered around the Future Land Use Map (FLUM), which shows how the Office of Planning intends to develop the city, such as adjusting low-density areas zoned for single-family homes to allow for higher-density apartment buildings. Developers looking to do so would no longer have to appeal to the Zoning Commission and undergo a Planned Unit Development (PUD) process, during which developers have until now offered to add more affordable units or other structures for the community, such as parks, in exchange for exceeding the area’s zoning laws.

Critics say this process has allowed groups to hold up production of thousands of units of new housing in court by appealing Zoning Commission decisions when they disagree with the final PUD agreement. Proponents argue that low-income residents are left with no other options to resist high-end development that does not serve people who already live in the community and may lead to them being priced out of their own neighborhoods.

The committee print added some language, such as Section 305.11 in the Land Use element, which tells developers “community engagement and actions shall be undertaken to retain existing residents, particularly communities of color.” In a meeting on April 19, coalition members stated they are pleased with the increase of language that encourages more community engagement, but said the plan still needs more concrete language to require community involvement that residents can fall back on when developers do not comply.

Another Grassroots Planning Coalition member and an attorney at the Legal Clinic, Caitlin Cocilova, said that a rewrite of the Comprehensive Plan would be ideal, but ensuring that the amendments at hand will benefit lower-income communities in D.C. is still important.

“This document is going to be rewritten in five years,” Cocilova said. “It’s very long … it becomes kind of overwhelming for everyone involved, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t things that can be done to strengthen it and make it better and to not weaken it.”

In contrast, urbanist organizations like the Coalition for Smarter Growth and Greater Greater Washington, who initially advocated for similar goals to the Grassroots Planning Coalition, have been fully backing the Comprehensive Plan amendment as written since April of last year.

Alex Baca, policy manager at Greater Greater Washington explains that PUD cases have been held up in court, waiting for the comprehensive plan to be passed to make a decision. At the moment, 20,000 housing units including 4000 housing units are being debated in these PUD cases, waiting for a decision.

On April 14, Baca wrote an article about how the FLUM map will not eliminate community input, saying that building higher density units in low-density communities would prompt more Planned Unit Development cases in court, which requires community input. She maintains the testimony she made in November, urging D.C. Council to pass the amendment as soon as possible and push for a rewrite of the plan to be done by 2022.

“There is no good to be had to draw this [out] further,” Baca told Street Sense Media. “With the [Office of Planning] staff time that has been spent on this…we could have probably had an excellent rewrite by now, and it’s a f***ing shame that we’ve been squabbling over this document for over five years.”

Correction (04.29.2021)

This article has been updated to reflect the correct spelling of Councilmember Janeese Lewis George’s first name.