Members of the public were invited to testify at a Nov. 15 oversight hearing of the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services. Ward 7 Councilmember Vincent Gray, who chairs the Committee on Health, said that he called the hearing because “many health and human service agencies are struggling to meet basic expectations of performance.”

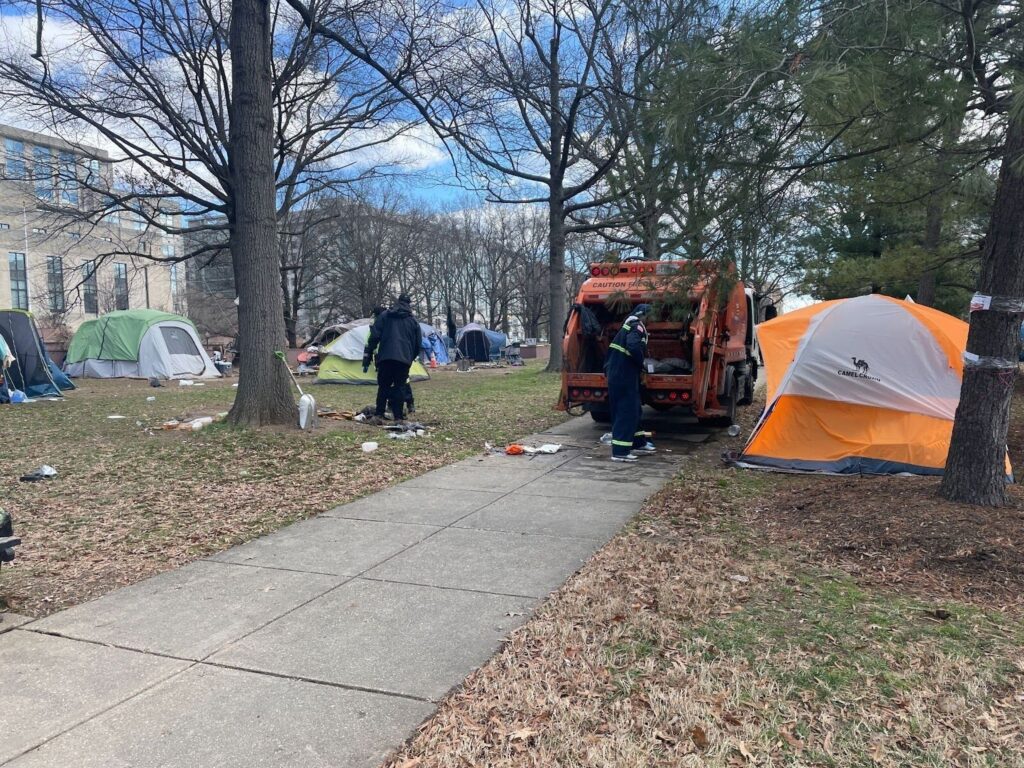

Most of the registered witnesses spoke about recent encampment cleanups, coordinated by the deputy mayor’s office, that occurred in Foggy Bottom on E Street.

Andrew Wassenich of Miriam’s Kitchen described them as the destruction of a community. “The cleanup on Nov. 2 was pretty much a show of brute force and it may as well have been a tank and a squad of troops from the way it was handled,” he said.

[Read more: our coverage of the November encampment cleanups on E Street]

King Mark, who lived in one of the encampments, said $1,000 worth of property was destroyed in the cleanups, including his friend’s birth certificate and Social Security card. Aaron Snyder, a GWU student, claimed he was punched and kicked by police officers while trying to protect a tent.

Gray questioned Snyder about the incident and asked if he had filed a report with the Office of Police Complaints. He had not, saying that he was more worried about the residents of the encampments.

Gray said it was possible to focus on both. “If folks, as you allege, are being physically abused by our law enforcement officials, and you can corroborate that, of course we would want to know that and we would want to have a complaint lodged that could be investigated,” Gray said. “But you didn’t do that.”

Synder said he would file a complaint that day. Another student, who identified herself as Andrea, said that she photographed and recorded the cleanups. She supported Snyder’s account and offered to make her work available to Gray’s office. He encouraged her to send it to him as well as to the deputy mayor. He commended all of the students for their activism.

Ethan Koczent, a GWU student, commended the sanitation workers present at the cleanup, saying the majority of them “stepped aside and said they wouldn’t be involved in throwing away people’s homes and lives,” One sanitation worker confided that they were close to sleeping on the streets themselves, despite their job, according to Andrea.

Public witnesses testified before the committee for approximately an hour and a half before representatives from the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services had the opportunity to provide their own statements before then responding to an hour of questioning from committee members. Deputy Mayor HyeSook Chung encouraged the public witnesses to review the city’s protocol for conducting homeless encampment cleanups, which she said was methodically created over the course of eight years in collaboration with legal advocates and nonprofit partners.

Before Chung’s testimony, Gray had asked several of the public witnesses if they were familiar with the rules surrounding encampments. “I think the issue at hand is that we don’t agree with the rules in place” Koczent said. “It’s either sleep on a bench where you freeze and get hypothermia or go in a shelter where you are assaulted. I’d rather break the law and stay in a tent town where I’m safe and protected.”

Chung said the city takes “great care in notifying people in encampments about what the protocol and procedures are and what ‘cleanup’ means.”

Witnesses disagreed with the government’s claim to clear communication. Koczent said that when he tried to call the numbers listed on the cleanup sign for more information, several did not work.

Samantha Ross, another GWU student, stated that “cleanup” was the wrong wording for the signs and that ‘eviction notice’ would be clearer for residents. Michael Burriss, one of the encampment residents, testified that he had led the tent community to rake leaves and throw away trash in anticipation of the scheduled cleanup. Burriss said that the police told him that residents could move their tents back once the cleanup was finished.

“What’s the point? Why are we making people move everything they own?” asked Arty Lowenstein, one of the GWU students. He said that some people had to take off work to be present for the cleanup. “If you are going to let them move back, why are we spending time to traumatize people and terrorize a community?”

The primary reason for doing a cleanup is for the safety of the residents who are vulnerable to public safety and public health risks, according to Chung. She said that the Department of Human Services and the Department of Behavioral Health outreach teams are doing individualized outreach to encampment residents on a regular basis. Gray asked for detailed outreach data, which the deputy mayor agreed to provide to his office.

According to several witnesses, the representatives from the mayor’s office that were present at the cleanup repeatedly told encampment residents to go to shelters.

“People live in encampments because tents provide shelter and privacy and because there is safety in numbers,” said Wassenich, the peer outreach specialist from Miriam’s Kitchen. “By sweeping these encampments the administration denies individuals these things. I suggest anyone who believes that a shelter is where homeless people should go should spend a night in one themselves.”

Wassenich testified that his clients have complained of bed bugs, being assaulted or robbed and struggling to maintain sobriety among drug users in shelters. He said that at least one-third of homeless individuals prefer to stay outside even in the dead of winter.

The deputy mayor did not address shelter conditions in her testimony.

Jesse Rabinowitz, also of Miriam’s Kitchen told the committee that he has witnessed firsthand the harmful impacts of encampment cleanups on his clients. “Encampment evictions are often traumatic and do not address the root causes of homelessness” Rabinowitz said.

According to him, encampments rarely present a public health concern and, if they do, that should be the main reason why they are cleaned up. He alleged that neighbors’ complaints motivate cleanups, though the deputy mayor’s office has denied this in Street Sense Media’s past reporting.

All of the witnesses called on the mayor’s office to respond to this issue effectively and efficiently. Many of them stressed the dire need to fund affordable housing. Wassenich said that only six percent of this year’s homeless services budget goes to housing homeless individuals.

According to him, during 2015 the D.C. government spent $223,807 on encampment cleanups. “It’s shocking that this much money is not spent on helping homeless individuals, but on making their already difficult lives harder,” Wassenich said.

Public records obtained by Street Sense Media during that time period show that each unique encampment location generally required $1,000 – $4,000 to clean up. The outlier during the October- January quarter that the data represented was a recurring area near the Watergate complex that took $132,334.60 to repeatedly clear out during that three-month period, after which encampments returned sporadically.

Gray questioned Wassenich about what was included in the projected $257 million-dollar budget for city homeless services in fiscal year 2018. Wassenich responded that it includes

$30 million for a new shelter, $16 million for hotel rooms for families, and a significant amount for permanent supportive housing.

Rabinowitz added that this amount also includes $100 million that Mayor Bowser has committed to the housing production trust fund each year. “But regardless of the amount, it pales in comparison to the dire need for housing,” Rabinowitz said.

Burriss, one of the camp residents, echoed Wassenich’s testimony. “Why are you trying to take from someone who is less fortunate than you? If we can put together that small tent town and we can sleep together and have a small community, why can’t we do that? You want to change the nation? That’s how you change it, go to the darkest part of our community and once you see the change there everything else will follow,” Burriss said.