The fight to end racial discrimination in the South has been told often and well, from North Carolina’s lunch counter sit-ins to Rosa Parks to Selma and Birmingham, but fights against the more subtle bigotry in the North have gone largely unsung – until now, that is.

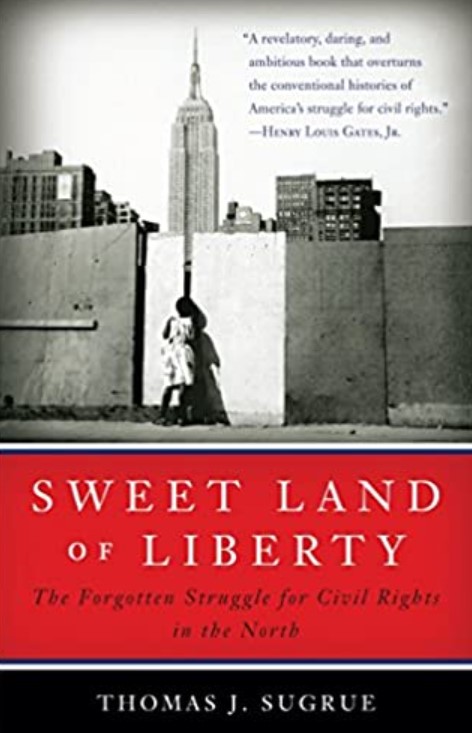

In his sweeping Sweet Land of Liberty, The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North, University of Pennsylvania historian Thomas J. Sugrue recounts the battles to end racial discrimination in jobs, public accommodations, education and housing in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and other northern cities and their suburbs.

He brings to light in great detail and thoroughly readable prose the long and not always successful fights by outraged church women, local educators, housing activists, union organizers and radicals of every stripe. National organizations battling with them were, among others, the Urban League, the AFL-CIO and the YMCA.

However, many of these northern efforts came with widespread rioting that both promoted some antidiscrimination moves and, at the same time, set some back.

But the North was different from the South. The South had its laws mandating separation, but the bigotry in the North, if more subtle, was just as pervasive.

Sugrue writes that most northern communities did not put up signs to mark separate drinking fountains, restaurants or swimming pools. In fact, only a few northern communities had legally segregated facilities. It was the private and community behavior that created and enforced discrimination.

He continues, “Northern blacks lived as second-class citizens, unencumbered by the most blatant of southern-style Jim Crow laws, but still trapped in an economic, political and legal regime that seldom recognized them as equals. In nearly every arena, blacks and whites lived separate, unequal lives.”

A seminal effort in the struggle to end racial bigotry in the North and the South, was the 1963 March on Washington that brought together a quarter million people to hear the nation’s civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., put out a call for jobs and freedom.

The call highlighted the longtime effort to end discrimination in the hiring and promotion of blacks, an effort led for years by socialists and religious leftists. This national effort for job equality was waged most effectively in northern state legislatures and city halls, where there were large black populations.

Public accommodations was another battle. The fight to open these, Sugrue says, was fought in great part by community organizers through sit-ins and legislative lobbying. He writes that “Activists chipped away at the customs that separated the races until the sight of blacks at northern lunch counters, hotel lobbies, theaters and amusement parks was not unusual – at least in big cities.”

The battles in education and housing were far different, Sugrue explains, with the separations due in large part to where blacks lived. Brown v. Board of Education was a sea change, of course, but, in most cases, blacks lived apart from whites, and this spurred activism on both sides of the issue. Busing followed, but so did “white flight” to the suburbs. “The inadequacies and possibilities of Brown sparked an extraordinary wave of grassroots protest, school boycotts and litigation,” Sugrue writes.

In housing, the fight was also fierce, and local. To meet the growing demand for housing, new communities sprouted up, including the “Levittowns,” mass-produced suburban communities planned and built by William Levitt. But by Levitt’s orders, there would be no blacks in them.

The result was a massive gap between supply and demand, and blacks paying more for housing than whites, with newcomers from the South crammed into old and rundown housing, mainly in the dense central neighborhoods left behind by fleeing whites. Langston Hughes described these black neighborhoods as the “land of rats and roaches, where a nickel costs a dime.”

But this would change, if gradually, again through community action and legal action, until there were growing arguments in social psychology journals, general interest magazines and in church newsletters that such bias was not in the public interest. Protest politics followed.

Sugrue writes that postwar efforts to change the hearts and minds of Americans worked to a degree; what feelings they might have had were not expressed publicly, but the softening of overt comment had not ended racial inequality. “The stark disparities between blacks and whites by every measure – economic attainment, health, education and employment – are the results.” And these great inequities continue today.

As Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the March on Washington brought about far-reaching changes in American racial attitudes, there is similar hope among many that Barack Obama’s election might bring about a further reconciliation of the races.