D.C. police temporarily detained a pregnant Black woman during an encampment closure on April 17. The police held her in a police van for an hour while D.C.’s Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS) removed her encampment, throwing away her tent and the majority of her belongings.

Tavoncia, the encampment resident, had lived in a wooded area behind a boarded-up house in Deanwood for about six months before the closure. (In the police report for the incident, the resident’s name is spelled Tavonicia, but she spelled it to Street Sense as Tavoncia).

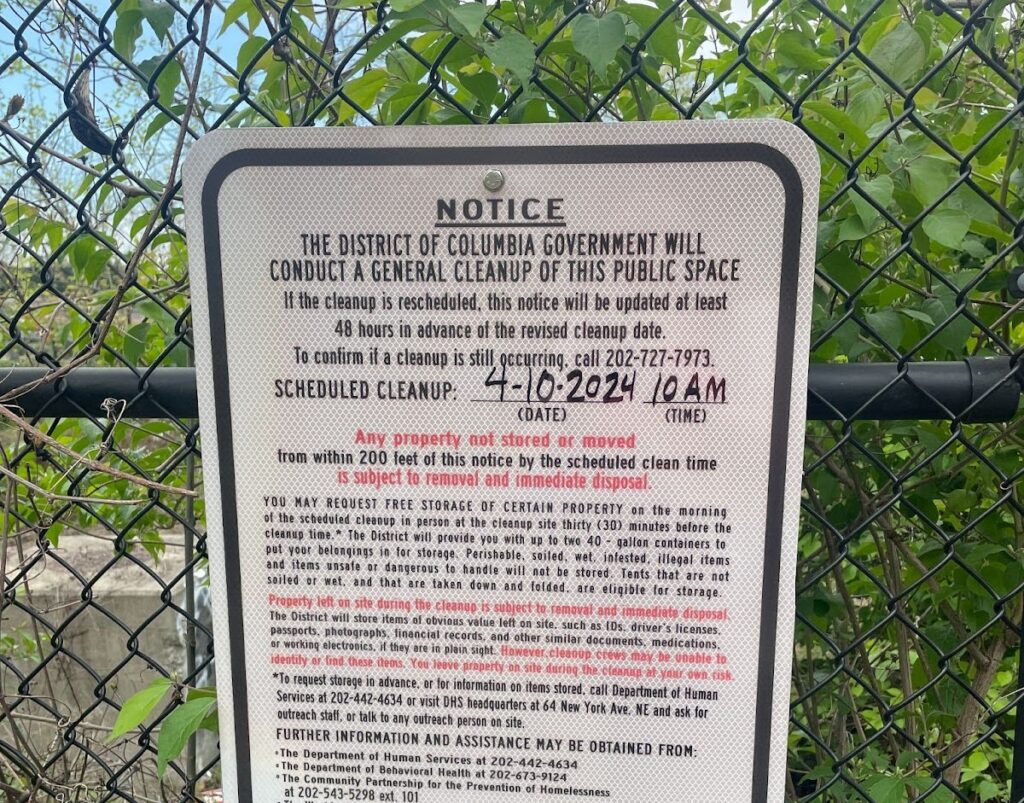

On March 25, a sign was posted on a fence outside the encampment notifying Tavoncia of the impending closure, but Tavoncia said in an interview with Street Sense during the closure she hadn’t noticed it. She said she usually enters and exits her encampment through another entryway, and rarely passes by where the sign was posted.

“You put up one sign. There are three entrances,” Tavoncia, who does not have a phone or email address, and has had limited contact with the D.C. government, said. “I don’t see that, I don’t walk that way.”

The encampment closure was scheduled to begin at 10 a.m. on April 17, but Tavoncia requested “a couple of hours” to gather her belongings since she hadn’t known about it. At 10:40 a.m., DMHHS Encampment Response Program Manager Jamal Weldon told Tavoncia and legal advocates on the scene that DMHHS would begin the clearing at 11 a.m.

Tavoncia said that while Community Connections, a homeless outreach group contracted by the city, had stopped by to let her know about the impending closure the month prior, nobody from the city had reached out to her since, although church groups occasionally came by to offer her food. Community Connections did not respond to requests for comment.

“I’m not gonna move fast,” Tavoncia said, citing her high blood pressure and swollen feet due to being three-to-four months pregnant. She expressed frustration, repeatedly saying she felt rushed and bullied.

At 11 a.m., DMHHS officials and police entered the encampment and began speaking with Tavoncia, who was in her tent. Within 20 minutes, eight police officers and recruits had arrived and surrounded Tavoncia’s tent, and an ambulance and police van parked nearby. Asked later about the police presence, an MPD spokesperson wrote there were only six officers and recruits, and did not respond to clarification requests.

At 11:26 a.m., police officers began removing items from Tavoncia’s tent, to which she loudly protested. By 11:28 a.m., she emerged from the tent to talk with the police officers. Less than a minute later, while Tavoncia was speaking with the officers, one took hold of her arms and put her in handcuffs. Police later said that they were engaging in an FD-12, or involuntary hospitalization, and the police report said Tavoncia was “stopped as a result of an interaction with the Department of Behavioral Health.”

As police restrained her, Tavoncia complained of a shoulder injury, and notified police of her medical conditions — including her pregnancy and high blood pressure, which she said led to a stroke last year.

Tavoncia also told officers she needed to urinate and asked them to let go of her so she could relieve herself (pregnant people often need to urinate more frequently). Officers refused and soon after, Tavoncia relieved herself in her clothes while still being held by the arms by two officers.

After handcuffing Tavoncia, police led her out of the encampment, where an EMT checked her vitals. Police soon placed her in the back of a police van in the same clothes.

When asked for a comment on Tavoncia’s handcuffing and subsequent urination, a spokesperson from MPD wrote to Street Sense that Tavoncia was holding a broken pipe. Tavoncia said while being handcuffed that it was a piece of her tent.

Tavoncia remained in the back of the police van for nearly an hour, handcuffed, while DMHHS officials cleared the encampment. Tavoncia later told Street Sense police told her she would be taken to a nearby hospital as part of the FD-12, but she instead remained in the police car at the scene until 12:28 p.m., when police released her.

According to an MPD report, Tavoncia was detained “until a final determination was made as to whether or not she was an FD-12 candidate.” Ultimately, D.C.’s Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) determined that she did not meet the criteria for an FD-12, at which point she was released. Officers can carry out an FD-12 only if “there is reason to believe that a person is mentally ill and, because of such illness, is likely to injure self or others if not immediately detained,” according to a document from DBH’s website.

MPD did not comment on why the officers engaged in the FD-12, directing questions to DBH.

Tavoncia was visibly distressed and angry when she was released. “I got locked in a fucking cage,” she said when asked about the experience.

While Tavoncia was detained, DMHHS staff and police officers disposed of all of the items at the encampment except for three trash bags full of Tavoncia’s belongings. According to Weldon, the DMHHS program manager, those bags contained “clothing items and things she had already been packing.” Among the items thrown away were Tavoncia’s two tents, a pair of roller skates, a license plate, and blankets.

“Where’s the rest of my stuff?” Tavoncia repeatedly asked upon returning to the cleared encampment.

While Tavoncia asserted she had not been given enough notice of the clearing, Weldon argued there had been sufficient prior notice, given the signage posted and outreach from Community Connections. “It has been permanent that this space must be clear since last year,” Weldon told Street Sense. D.C. initially closed the encampment in April 2023.

After print publication, a representative from DMHHS and DBH told Street Sense that DMHHS provided verbal notice to Tavoncia three and a half weeks prior to the closure of her encampment, and that she had “verbally acknowledged” that she understood that the encampment would be closed. The representative also wrote that the sign alerting her of the closure had been placed at the encampment’s “primary entrance” that same day.

After the closure of the encampment, the DMHHS/ DBH spokesperson told Street Sense that Tavoncia left the site with her social worker, who DMHHS had requested to assist her. Tavoncia refused attempts to offer additional support from Community Connections, DBH, DMHHS, and MPD, the representative also wrote.

According to DMHHS’s encampments website, the encampment was closed due to fire hazards, and Weldon said that an “explosion” had taken place in the area the prior year. Tavoncia said a previous resident of the encampment had been cooking in their tent and accidentally set the tent on fire. She assured Street Sense she had not been involved in the incident.

At its peak, the encampment had around 13 tents, Tavoncia said. She came back to the area six months after the last closure, and told Street Sense that she sleeps there every night.

“They didn’t give me no housing,” she said. “They’re fucking with a homeless pregnant person for no reason.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated from the print version to include DMHHS comments made after the print deadline.