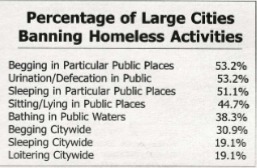

A study by the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH) in late 2003 found that nearly 70% of the cities surveyed have passed new laws aimed at curbing activity by homeless people, often related to routine acts of daily living and making survival on the streets tougher than ever before.

Donald Whitehead, executive director of the NCH, said cities were evaluated based on anti-homeless legislation, enforcement of penalties, general political climate, hate crimes and local activism. While his study, Illegal to be Homeless: The Criminalization of Homelessness in the United States found some cities friendly and others mean, he expressed concern at the fact that none of the cities surveyed demonstrated adequate shelter space.

“Cities must have resources in place to provide services at all times,” said Whitehead. He added that many of what he referred to as “anti-homeless laws” is just attempts to sweep problems under the rug, rather than solve them. Additionally, Whitehead felt that while many cities are more sympathetic in the winter, when summer comes around they are much less friendly.

“There is a lot more compassion when the weather is worse,” said Whitehead. “The sun can’t come out for more than two minutes before the hypothermia shelters close.” Whitehead also said that many officials feel that their cities look a lot nicer if homeless people are not part of the landscape.

While D.C. did not appear on the list of “meanest cities,” area officials are still using other methods to alleviate some of the area’s persistent problems surrounding homelessness.

“People may not get prosecuted here, but their lives are disrupted, said Ann Marie Staudenmaier, staff attorney with the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless. Staudenmaier stated that while the District does not have anti-homeless legislation seen in other cities, it is by no means friendly and welcoming to homeless people.

Staudenmaier also asserted that the Metropolitan Police (MPD) and The Department of Public Works use intimidation methods such as property sweeps, where according to Staudenmaier, the belongings of homeless are taken and destroyed.

“They’re saying they’ve got an obligation to clean up public space and technically they’re probably correct, “ she said. But our position is that if you take someone’s stuff, you can’t destroy it – it isn’t garbage.”

Selective enforcement is another problem Staudenmaier cited, stating that laws are more strictly enforced against homeless people as opposed to college students, for example, who may not be treated as harshly for offenses life public urination. Staudenmaier added that police crackdown on people for sleeping in public or demand to see identification, and police may ticket a homeless person for having their storage in a public space, while tourists set down their bags in a park will most likely not be approaches by authorities.

“Police don’t necessarily use anti-homeless laws,” she said. “But they nevertheless engage in a pattern of harassment.”

On the other hand, Lynn French, the District’s Senior Policy Advisor for Homeless and Special Needs, said the MPD undergo training, at least once a year, through a program with the Department of Mental Health, and the Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness to educate police on how to deal with homelessness. She added that during property sweeps, police do not take people’s possessions from them, but that under heightened national security guidelines, bags left unattended may be swept regardless of what they contain.

“There is no MPD policy to harass homeless people at the request of business owners,” French said. “MPD’s policy is to enforce the city’s laws.”

Agreeing, Steve Cleghorn, deputy executive director of the Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness, said that D.C. is not inhospitable to homeless people, and substantiated French’s assertion that the homeless are not forced off the streets, with the exception of occasional security sweeps necessitated by concerns of terrorism.

“Even in the winter, when some people are absolutely determined to stay on the street, they can’t be forced inside,” Cleghorn said. “They might be given blankets instead.”

Cleghorn stated that while D.C.’s only policy applies to panhandling, most policies are “common sense laws,” which bar activities already prohibited by other laws, such as public drinking, bathing, urinating and sleeping in parks.

There are laws against public inebriation, but those people are supposed to be picked up and taken to sobering stations around the city, not to jail,” said Cleghorn. “D.C. police strike a balance between being helpful and maintaining public safety.”

Some of these local improvements are attributed to D.C.’s downtown business improvement initiative, which has resulted in efforts to clean up the area while still providing needed services and support to homeless people. For example, service centers provide meal programs instead of merely pushing people out of sight.

Most of the suburbs of Washington have polices and laws similar to those in the District, and Cleghorn feels that the D.C. metropolitan area, including parts of Southern Maryland and Northern Virginia, is in some respects very liberal with regard to services provided, including beds, meals and medical care.

In addition, Neighboring Montgomery County is currently developing a policy on Panhandling to give lawmakers and others guidance on how to deal with the increasing population. This policy is part of the county’s overall attempt to craft humane laws to address the problems faced by – some would say created by – homeless people, particularly those who panhandle. Yet according to Cleghorn, many cities are on their own with regard to developing policies because very few statutes exists that specifically address homelessness.

“We really don’t know very much about the problem,” said George Leventhal, Chair of the Montgomery County Council’s Health and Human Services Committee. Leventhal went on to say that the issue is not whether to crackdown on people who panhandle by rather, to learn who needs help and what kind.

“I don’t think we’ve made enough of an effort to help people who need help,” he said. “We want to initiate relationships to assist people in finding food, shelter, counseling, drug treatment, or whatever else they need. If people are begging for help, I want to see that they get help.”

Leventhal added that on any given day there are 1,200 homeless people in Montgomery County, and said that there should also be a network of specialty providers in place who can assist the homeless.

“The spare change they get from some people is just not enough.”