72-year-old Ruth Barnwell has been watching the Congress Heights apartment where she has lived since 1982 crumble around her. She has no heat or air conditioning. When she had bedbugs last year, it took four months — and an interview with local media — for them to be exterminated. Mold grew in her walls when a leaky roof went unfixed. She and her neighbors have complained of rodent infestations, flooded basements, broken front door locks, and weeks’ worth of garbage piled up outside. Repairs, when they happen at all, are “shoddy and patchwork.” Meanwhile, rent continues to climb.

The trouble didn’t start, Barnwell said in an interview, until her building’s owner, Bethesda-based Sanford Capital, announced plans to partner with development group CityPartners DC and raze her building along with four others located a block away from the Congress Heights Metro station. In their place two high-rises would be constructed: one an office building, the other a 208-unit apartment complex with ground-floor shopping. Since the developers’ plans were made public, Barnwell said, maintenance calls have tended to go unanswered.

“We’ve been living in horrific conditions, which is their way of trying to evict us and make us move,” said Barnwell, who is the president of the Alabama Avenue/13th Street Tenant Coalition.

Three years ago, most of the buildings’ 61 units were occupied. 13 renters remain. Most are elderly and live on fixed incomes. Those who aren’t, Barnwell said, work for low hourly wages.

“The whole point of our development vision is to create something with better conditions and better development use for those tenants and the entire community,” said Geoffrey Griffis, principal owner of CityPartners, in a phone interview.

CityPartners is the “master developer” behind the proposed project, according to Griffis. Sanford Capital purchased the four apartment buildings at 1309, 1331 and 1333 Alabama Ave. SE and 3210 13th St. SE for about $2.8 million, according to an October 2015 Washington Post article. CityPartners and Sanford submitted the redevelopment plan together.

Sanford Capital has offered residents the right to return at their previous rents once the project is completed. Griffis said a plan to temporarily relocate residents, then invite them back, is on public record at the Office of Zoning and legally bound by the District.

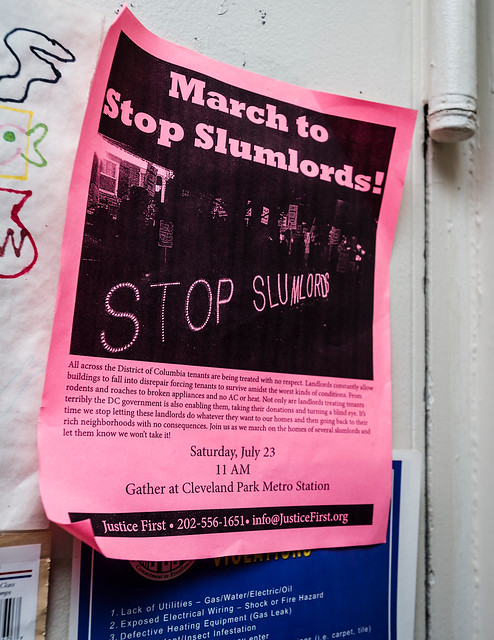

But tenants and advocates are skeptical, saying the promise has never been made in a written contract despite multiple requests from their lawyers. Developers frequently renege on agreements that are not explicitly written down, according to Eugene Puryear of Justice First, a tenants’ rights group.

“Any person who works on housing would tell you that that happens all the time,” Puryear said. “If it’s not written down, they’re not going to do it.”

Sanford has also offered tenants tens of thousands of dollars in buyouts to convince them to move, Barnwell said. However, according to Barnwell and 67-year-old Robert Green, another Congress Heights resident, the developer did not make it clear to residents who agreed to the buyouts that they would not receive the money until every single resident moved out. Many have ended up in shelters, Green said.

Sanford Capital declined to speak with Street Sense.

Will Merrifield, a lawyer with the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, has been working with the Congress Heights tenants for three years. According to him, Sanford Capital acquired the four buildings between 2009 and 2010.

“It feels like they just threw us to the wolves.”

Residents are determined to stop Sanford’s redevelopment, as they believe it will mean displacement from their neighborhood for good. They testified before the Zoning Commission in January 2015, before the developer’s PUD was accepted.

“These buildings used to be a nice, comfortable, safe place to live, but not anymore,” Clarence Taylor, who lives at 1331 Alabama Ave. SE, said at the Zoning Commission hearing. “Everything just went downhill since Sanford Capital has owned them … It feels like they just threw us to the wolves. I don’t feel safe.”

The D.C. Attorney General’s Office filed a lawsuit against Sanford Capitol in June of 2016, citing “repeated housing code violations that pose a serious threat to the health, safety, or security of the tenants.”

The same office sued Sanford again in October for conditions at Terrace Manor, another apartment complex in Southeast D.C.

Tenants and their lawyers are also often in court with the developer. Green said he and his fellow tenants have taken Sanford to court at least six times in the past three years.

He and his neighbors spent two weeks without heat last year. Two years ago, a heating outage lasted for two months straight. Green said maintenance workers frequently arrive without proper training or tools, and repairs are delayed for extended periods of time while parts are ordered. He also said some of his neighbors have been served with eviction notices not signed by a judge — an illegal order in the District of Columbia.

Griffis said he had no knowledge of these practices, as Sanford Capital—not CityPartners—owns the buildings.

In Conflict, an Opportunity

Sanford’s plan is stalled while ownership of one of the buildings involved, 3200 13th St. SE, is disputed. The building has stood empty for decades under a 40-year covenant with the District to be used for affordable housing.

Businessmen Zed Smith and Kevin Elmore purchased the apartment with a $920,000 loan from the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) in 2008, according to the Washington Post. They said they would use the loan to refurbish the building and house youth aging out of foster care. The building stands undeveloped and empty today, and the loan has not been repaid.

The building was recently transferred from the owners to DHCD “under a deed in lieu of foreclosure,” according to a statement emailed to Street Sense by Gwen Cofield, the agency’s communications director. DHCD will maintain control of the building until a lawsuit between the former owners and a potential purchaser is settled, at which point the agency will begin accepting bids for its ownership. The highest bidder will have to adhere to the building’s original affordable housing covenant, the statement said.

Whoever wins the bid for the vacant 3200 building, tenants have an opportunity to maintain the four occupied buildings with the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act. In the District, an owner planning to sell or demolish a property must give current tenants the opportunity to buy it before involving third parties. Tenant organizations can band together and take out loans themselves, or enlist the help of other developers or nonprofits, according to Eugene Puryear.

Puryear said the District Opportunity to Purchase Act, or DOPA, also gives the mayor’s office the right to purchase buildings in which at least a quarter of the units are affordable housing. By law, the mayor would then be required to further increase the number of affordable units.

If TOPA fails, advocates say, the Congress Heights buildings would be good DOPA candidates. In the eight years since D.C. Council unanimously passed the law, however, it has never been implemented. The mayor’s office has no funding source for DOPA, according to a City Paper article published in March 2015. “In the two and a half years I’ve been working on this, they’ve been saying they’re going to finalize the rules,” Puryear said.

DHCD hopes to fund and implement the rules in 2018. Director Polly Donaldson said in a Nov. 9 press conference that a draft of the rules will be issued in 2017, according to Cofield.

Whatever happens, residents are determined to keep fighting.

“I don’t have nothing else to do but stand up for myself,” said Gloria Ward, who has lived in Congress Heights for 35 years. “At this point, I have to, because I’ve seen the way they don’t care….the only thing they want is us out of this building.”

“We’re not the only ones. They’re doing this all over the city,” Ward added.