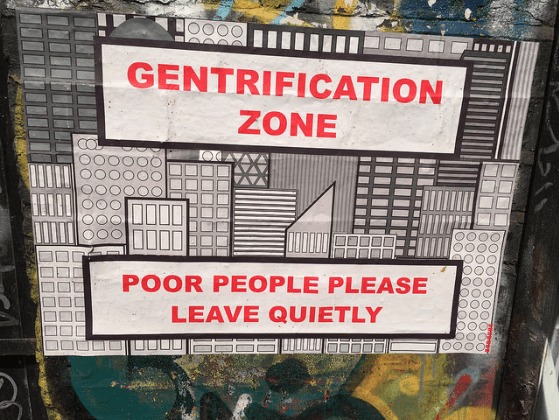

Should the city government help people at the bottom who are trying to hold on to the housing and neighborhoods their community has relied on for generations? Or should city policies focus on the incoming professional class, which prominent social scientist Richard Florida refers to as the “Creative Class?”

D.C. needs both, says the Bowser Administration. How to balance them for the betterment of all is the difficult part. Major metro areas across the country are facing the same dilemma. Is there any chance the problem of old poor versus new rich can be resolved satisfactorily in D.C.?

Attorney Ari Theresa referred to Florida’s concept of a creative class in a complaint filed in the U.S. District Court in April and amended last month.

The complaint Theresa filed in support of four destitute women against the D.C. government accuses the Bowser administration — along with the past Vincent Gray and Anthony Williams administrations — of acting in “collusion” with city officials, developers, builders, and planners, against poor people. Theresa claimed the results these actions have produced are racist.

In the District of Columbia, “Chocolate City,” the people struggling most to hang on to housing and keep up with rising costs are overwhelmingly African-American.

Theresa, a civil rights attorney who represents many clients in destitute communities, brought the complaint against the D.C. government, the city itself, several developers, real estate agents, and builders. It alleges discrimination against four low-income clients who do not want to leave their current residences, which include Barry Farm public housing and the historic Anacostia area. These are poor communities where the clients and their families have been hanging on for many years, observing modernization efforts they cannot afford, and depending on their communities for support.

Paulette Mathews, for example, a 20-year Barry Farm resident, wants to stay where she has been for so long, without it being touched by builders of a new subdivision. Some members of her community want to legally block developers from destroying the public housing units they’ve relied on for years.

A response motion for summary judgment filed in the same court says Matthews and the other women do not have legal standing to bring the case because they have not had any direct injury, which is required in all civil rights complaints. Their housing units are government property.

However, it is Theresa’s position that the women have lived in their neighborhoods for years and therefore are affected directly, or “hurt,” by gentrification.

The case is still in court and no official involved in this dispute was willing to discuss it. All inquiries were directed to the Office of the D.C. Attorney General for comment.

Matthews and the others plan to continue to fight the city.