Sasha Williams thought she’d found a new place to live. A survivor of domestic abuse, severe depression, and years in the streets, she’s been trying to move her and her four-year-old daughter from their current apartment into a safer neighborhood before her new baby is born in August.

The problem? The apartment building has denied her on the grounds of bad credit—despite the fact that the housing voucher she’s held for over two years guarantees she will be able to cover the rent. Frustrated by what she perceives to be discriminatory treatment, Sasha sees it as just one more setback in a long-standing, seemingly interminable fight for housing.

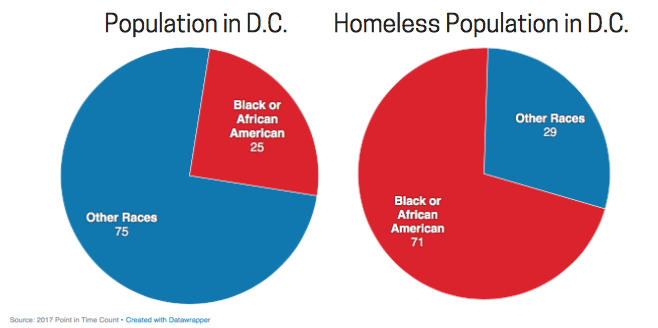

It’s a fight that many Americans—particularly those living in the nation’s capital—are losing. The graphs below illustrate the breadth of the homelessness crisis and what can be done to solve it.

Homelessness is a national crisis.

According to an annual point-in-time count, over 549,000 people were homeless in the U.S. on a single night in January of 2016—more than the populations of 62 countries around the world. Twenty-nine percent of those people were in families with two or more children, and 32 percent were reported to be living outside. Despite the efforts of organizations across the country to raise awareness about this issue, homelessness has barely declined since 2007.

Things are particularly bad in Washington, D.C.

The nation’s homeless crisis is near its starkest in the nation’s capital, where the District is lagging far behind the national average in combatting homelessness.

D.C.’s biggest problem lies with its inability to effectively address the increase of families experiencing homelessness. While the national average for individuals in homeless families decreased by 2.6 percent from 2015-2016, D.C.’s average increased by over 34 percent.

Homelessness knows no race, gender, or age, affecting nearly every group imaginable. There are certain categories of people, however, who bear this burden at a higher rate. Blacks and African Americans represent a disproportionate number of homeless people in the D.C. Metropolitan Area relative to their percentage of the area’s population.

From pre-K to college, students across the country are also experiencing large degrees of homelessness. There are currently enough homeless American children to fill American University’s enrollment 10 times. The lack of a stable home has a devastating effect on a student’s likelihood of furthering their education: only 3.4 percent of homeless students who enroll in 12th grade attend college the next year.

The rising cost of housing is a root cause of homelessness.

The causes of homelessness are as multifaceted as its constituents, but the most obvious in D.C. is the ever-increasing cost of housing.

D.C.’s minimum wage relative to these rising housing prices exacerbates the problem. A District resident earning minimum wage would have to work 93 hours per week in order to afford a one-bedroom rental at the Fair Market Price.

D.C. has the second-highest housing wage—hourly pay necessary to afford a two-bedroom apartment without spending over 30 percent of income on rent—in the country.

Solutions should be based on Housing First.

The D.C. government’s reliance on rapid re-housing—a model that grants people experiencing homelessness temporary, short-term rental assistance and services—has in many cases done more harm than good, often landing families back in shelters. As of October 2016, one out of every eight families in D.C.’s shelter system had already gone through a rapid re-housing program at least once. Further, families in such programs are forced to allocate an average of 40-60 percent of their income towards their rent, leaving them severely rent-burdened and incapable of providing for themselves.

Contrasting the failures of rapid re-housing is the Housing First approach, a method that research has proven to be successful in permanently moving people out of homelessness. Unlike rapid rehousing, Housing First prioritizes providing those experiencing homelessness with permanent housing as quickly as possible, providing other supportive services only after a person is firmly secured in housing—an approach founded on the principle that people will respond better to treatment and or help if they have a secure roof over their heads.

In Utah, Housing First programs helped the state reduce chronic homelessness by 91 percent in 2015. In Denver, Colorado, emergency-service costs alone went down 73 percent for people put in their Housing First; the program has proved to be an extremely cost-effective approach to ending homelessness.

Another jurisdiction that implements this Housing First technique is just across the river from D.C. in Arlington, Virginia. Crediting its participation in the 100 Homes campaign, nationwide Zero: 2016 Campaign, Homeless Services Center, and continued implementation of a Housing First model, Arlington has been able to specifically target the populations in their city experiencing the highest rates of homelessness.

Large-scale data is critical in understanding homelessness and its potential solutions, but it’s also imperative to remember that these data points represent people. Sasha Williams is a statistic present on multiple graphs used in this piece, but she is also a woman trying to move into a safe neighborhood so she can raise a young family. She is funny, engaging, smart, and interested in filmmaking. She, like all of the other people represented in the data on this page, just wants a place to call home.