Recently, high school seniors in a Social Justice in Action class at Gonzaga College High School — which is located blocks from the tent communities that were removed from underpasses in NoMa — learned about the city’s Coordinated Access and Resources for Encampments program. Here are their thoughts about the approach.

AUSTIN ZIELLER

As a senior at Gonzaga College High School, I have had nearly four years to familiarize myself with the community just beyond our school’s gates, which has recently experienced an influx in encampments. Although efforts by the government are providing a little hope to the issue, they are not being implemented in a just and effective manner.

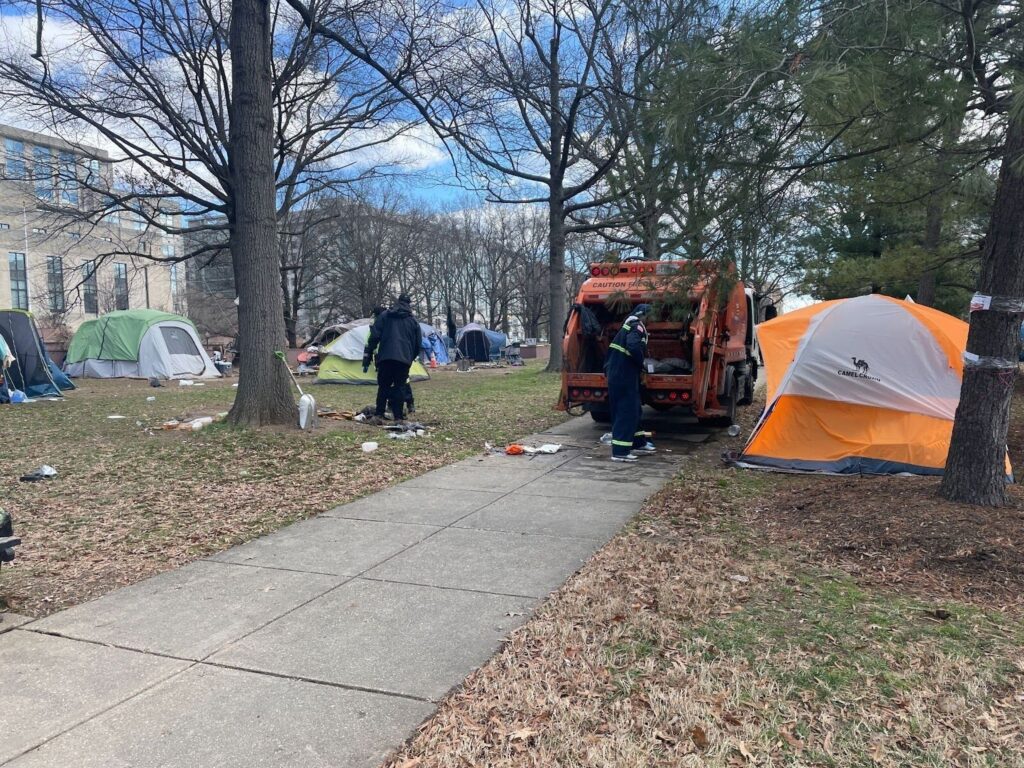

There are two components of the plan to rid the city of encampments. First is removing the residents, and second is providing them with housing. The actions currently being taken against encampments are failing to connect the two parts, and are in turn hurting the citizens of D.C. being removed from their homes.

Throughout my 18 years on this planet, I have lived in three different houses. While in a literal sense they are all very different from each other, they are the same because of what they mean to me. They provide me with safety, comfort, stability, privacy, and a sense of belonging. Housing should not be something experienced by a majority of Americans; it should be experienced by all. Housing is a human right, not a commodity.

So for the sake of these D.C. citizens, the government must solve the issue with housing before removing the encampments; not during or after. The inability to immediately place these people in homes is putting them in difficult situations, harming their well-being, and ultimately not doing anything to help move our city in a direction that will put an end to homelessness. We need to stop making efforts against encampments about cleaning public spaces and start making them about ensuring stability, safety, and well-being for human beings by means of one simple thing: a home.

WILL RICE

The last few decades have ushered in major urban development in Washington D.C., accelerating gentrification and contributing to soaring property prices. With this drastic growth, we cannot forget about our neighbors experiencing homelessness, an issue with major implications that has become far too common within our broader community.

The government response to this has been to evict residents from their encampment shelters, sometimes even in an inhumane manner that neglects the intrinsic dignity of the human person. While the recently enacted Coordinated Assistance and Resources for Encampments pilot program does include necessary case management and health support for the unhoused, it fails to ensure that housing is guaranteed to the encampment residents before removing them. Housing is a human right, a basic building block that is foundational to life. It is an injustice to strip people of this right.

Recently, my Social Justice in Action class at Gonzaga College High School visited the John and Jill Ker Conway Residence, which is a modern housing option for low-income and formerly chronically homeless residents, particularly veterans. For me, this experience revealed that dignified, yet affordable, housing for the most vulnerable of society is possible. The Conway Residence, which applies the Housing First model, represents a practical, sustainable, and just solution to a pressing issue. An important lesson can be learned from the success of this approach: The government must focus on housing the homeless before trying to frantically clear the streets of encampments.

PETER MILDREW

Serving D.C.’s homeless population is life-giving. I volunteer at the Father McKenna Center, a homeless day shelter and food pantry on my high school’s campus, and there’s a reason why I can’t count how many times I’ve been there. I don’t serve to fulfill hours or meet requirements for my Social Justice in Action class. I serve because the love that I can give to the homeless is reflected back into my soul every time I’m there. Although getting to know some of the men who are guests at the McKenna Center has granted me alternate views of what homelessness really is, this love triumphs over anything I could get out of serving. This sensation, almost like a warm embrace, is life-giving. The D.C. government obviously doesn’t know what this sensation is.

While writing a letter to D.C. council members about my concerns over the oxymoronic CARE program, I detailed my experience as a servant of the homeless. I explained that, in order to amend all that is wrong with this program, like the backwardness of evicting encamped people before having available housing, or the dehumanizing manner of tearing down any semblance of housing left to a person, the D.C. government’s view of the homeless needs to be amended. This isn’t to say that the entire D.C. government is ignorant of the humanity of homeless people. The fact that a policy like this is even in place is a good sign and demonstrates that there is an awareness of the homelessness epidemic. I’m just frustrated that its implementation is so problematic and hurtful to people who are already so hurt.

TYLER KACZMAREK

How can a public housing program destroy the housing of the very people it seeks to help? While the CARE program seems to be a step in the right direction – providing homeless residents with case managers and other resources – it has sparked a crisis regarding the encampments themselves. Currently, residents are being forced out of several encampments, forced to sleep on park benches or sidewalks while they wait for the badly delayed housing provided under CARE. In this way, the CARE initiative is accomplishing the exact opposite of what it set out to do.

On its website, the D.C. Department of Health and Human Services says that its “protocol for cleaning public spaces is triggered when a site presents a security, health, or safety risk, and/or interferes with community use of such places.” We must ask ourselves: Who is part of the “community” that the department is protecting? Is it the upper- and middle-class businesspeople who travel past these encampments each day on their way to work? The “community” definitely doesn’t seem to include the residents of the encampments. If it did, the department would have to leave these homeless people alone, recognizing that they have an equally valid claim to the encampment spots as anyone else.

The D.C. government’s new CARE policy has the potential to create positive change, but this policy is no reason to move forward with the destruction of the city’s homeless encampments. Instead of bulldozing people in their own homes/tents, we must instead focus on our efforts to house the people within them. By putting people first, we remind ourselves that we are all human and that each of us deserves to be treated with the infinite dignity we contain.

FEDERICO SILVANI

D.C.’s approach to the encampments seems perfect. Besides cleaning parks and making them look nicer, it provides much-needed stability to the people experiencing homelessness. It would give them a place to stay where they’re safe from everything and can begin to rebuild their lives. This is exactly what D.C. needs to focus on — but we’ve been doing the opposite. By clearing the encampments before the people living there are housed, we are making their path forward much more difficult. Instead of searching for a job, they’ll need to look for somewhere to rest. And if they can’t stay in these established encampment communities, they’re forced to go to dangerous places alone.

The way in which we treat these people experiencing

homelessness enforces the myth that they are worthless human beings with no place in society. We are bulldozing everything they own in front of their eyes while telling them to leave without offering enough support. If D.C. would stick to the planned method of clearing the encampments, our entire community would benefit and improve. However, they decided not to take care of the people who need it most and now we are worse off. It would’ve been better if they simply hadn’t done anything and let the friendships and relationships developed in the encampments continue to grow.

DANNY BARRÓN

In order to help address homelessness, D.C. needs to focus on love rather than vanity. The CARE initiative, dedicated to helping those who are homeless find housing, has been carried out in all the wrong ways.

Some were lucky and were present on the day an incomplete and inaccurate census was taken, and they were able to get housing. Some were not as lucky. We see now that those experiencing homelessness are kicked out of where they live without any place to go. Instead of working with those on the streets until every last one is housed, it was decided that the encampment sites would be cleared no matter the population.

After hearing all of this, the question that radiated throughout my mind was, why? What rationale could explain how putting lives in danger fits with the message of a plan called CARE? The only answer I could come up with is that D.C. cares more about its streets looking pretty than anything else. Instead of rolling up its sleeves and doing the work, D.C. spends money on bulldozers to do it.

I am a senior at Gonzaga College High School right in D.C., and if this is the only conclusion someone of my age can come up with, then you have a hell of a lot of work to do if you want to get it right.

NICHOLAS BOLLMAN

The D.C. government’s encampment policy is a tale of polar opposites: A nearly-ideal policy on paper and the dystopian implementation of it. The new CARE program entails providing housing for residents of certain encampments while striving to eliminate said encampments entirely. From a logical standpoint, this is entirely sensible. After all, ending homelessness would result in the absence of people to occupy those encampments. However, the government made multiple mistakes that have made the program’s effects resoundingly negative. Primarily, evicting encampment residents prior to guaranteeing them their own set of house keys has been disastrous. Generally, these evictions prompt relocation, which severs any connections to social workers and programs, thus exacerbating homelessness. When coupled with the downgrading of the housing offer to rapid rehousing, which often places vulnerable families and individuals back on the streets after a year, the CARE program is all but caring for those experiencing homelessness.

I have served with Ward 6 Mutual Aid in the L and M encampments, and by doing so, I have observed what should be painfully obvious: Encampment residents want stability, autonomy, and agency. Their decision to abandon local shelters, which seemingly defies common sense, becomes much more reasonable for someone who desires control over their own life. The D.C. government has the opportunity to offer help that differs from the traditionally restrictive shelters, but it is currently squandering that chance by jeopardizing the security of the men, women, and children who reside in encampments, most exemplified by D.C. machinery injuring a man in his tent. Perhaps my stance will change with a re-implementation of this program that follows through with the original intent.

RODRIGO BORJAS

We live in a society that emphasizes doing things faster, more efficiently, and more cost-effectively. Technological advancements accompanied by an ever-progressing society have created a mindset in which we, as humans, view the world as a platform to make more money and climb up the social ladder without taking into consideration our worldly community. This “go, go, go” mentality is directly seen in the stance the government of Washington D.C. has taken in regard to encampments for the unhoused.

Homelessness is a state of being that affects millions nationwide and thousands in the District. The encampments that lined L, M, and K Streets (just to name a few) served as homes and communities for adults, children, and families alike. Just like you and I go home at the end of each day, these people do the same, only their homes are tents. In an attempt to “make homlessness rare, brief, and non-recurring,” the D.C government has enacted plans to remove encampments, guaranteeing members of these encampment communities housing. In theory, this program, referred to as the CARE pilot program, seems excellent.

However, encampments are being shut down before the people living in them are housed. The result: People are being displaced further at the hands of the government due to a desire to hastily end the problem of homelessness. We must remember that the unhoused are not things or problems that can be removed or ignored; they are people with quirks, interests, and personalities. Serving at the Father McKenna Center weekly for the past several months, I have interacted with all kinds of poor and vulnerable folks in our community. They are not one-sided individuals. Their problems are multifaceted and must be addressed now.

BOBBY DINGELL

We hear a lot about the tales of Jesus in church. One attribute people often ascribe to him is his love for the poor. This attribute often gets misinterpreted as Jesus being in favor of poverty. Jesus’s main goal was for his followers to be compassionate for the poor. Being compassionate and being in favor of something may come across as similar, but they in no way share the same meaning. For example, I can be in favor of giving all people experiencing homelessness homes, but that doesn’t mean I’ll do anything about it. Compassion, however, lives through our love and understanding to act appropriately.

The government needs to proceed justly on this matter, and they have to act on it soon. While attempts have been made to “clean up” many of these encampments, the cost of rent has been rising at a staggering pace. From 2001 to 2017, the percentage of renter households paying more than 30% of their income on housing increased from 42% to 48% as wages lagged behind rent. This gap has to close. In D.C. specifically, there are around 5,000 people experiencing homelessness while 17,000 apartments are vacant. The city should either raise the minimum wage or regulate how much landlords are charging for their spaces.

This city has the capability to do it. I’ve seen us come together through protests and public movements before. We just need to use the same energy to view the potential and beauty in our city’s low-income residents. They have been oppressed and unsheltered for too long and our government needs to take a look at Jesus Christ’s playbook of compassion and love for the most vulnerable in our community. Once we see, judge and act, justice will be kept. Amen.

GUYER KOPPLIN

A man shuffles down the dark, lonely D.C. streets at night. After moving from overcrowded shelter to overcrowded shelter, he is left with nothing but the cold pavement to call his bed. However, on the horizon he sees some hope. A tent community. After scraping enough money and dignity to enter a store to buy a tent from folks with leering eyes, he joins the community. Right away, he feels like he is at home. Although it’s not where he wants to be, it’s a start. After a few months of living in this community, he is ready to take his next steps forward. His life has been difficult, but the new proposal from the mayor’s office gave him hope. Rapid Housing. After being on the housing registry for so long, it seemed almost too good to be true. Then came the day. Early one morning the man was met with shouting workers, the sound of water whipping the concrete, and the industrial churn of bulldozers. In a few moments, the man starts from square one again.

This scenario is shocking and new to the people reading the news recently, but not to the people experiencing homelessness in the District. Between October 2015 and March 2016, D.C. spent roughly $172,000 in cleaning up homeless encampments. This new pilot program costs between $3 million and $4 million and includes support services as well as immediate housing. Although this sounds like the perfect solution for our nation’s capital, pitfalls are littered throughout. If the mayor’s office disbands encampments, they have effectively shuffled the people around and not solved the problem. If this plan is to be successful, the homeless people need to be guaranteed a home before their homes are destroyed.