The connection between mental illness and homelessness does not come as a surprise to those who spend their days working with psychologically-scarred veterans and deinstitutionalized hospital patients living on the streets or in emergency shelters.

But for a Los Angeles Times columnist, the link between a talented musician’s schizophrenia and his place on the sidewalk of the city’s Skid Row came as a devastating wakeup call.

“I was shocked and ashamed,” said Steve Lopez, Los Angeles Times columnist and author of The Soloist: A Lost Dream, an Unlikely Friendship, and the Redemptive Power of Music. “Ashamed that we’d never done anything about this.”

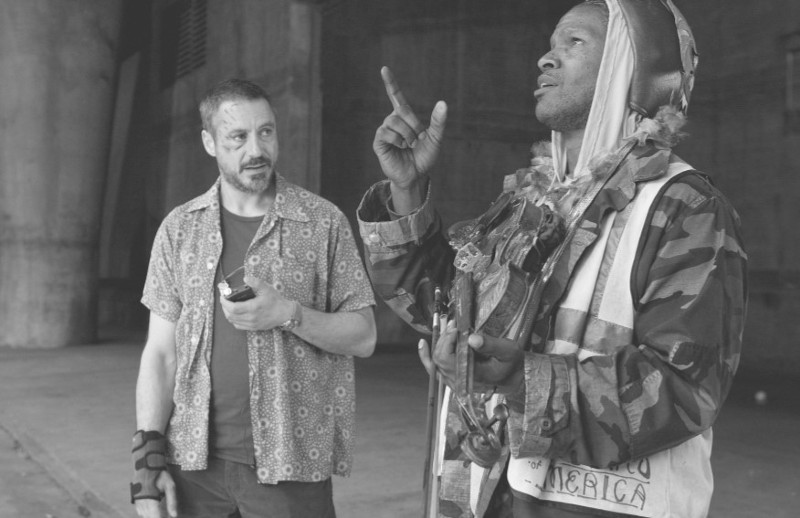

Speaking to a gathering of about 90 Congressional staffers Lopez described how the world of the homeless and mentally ill opened up to him when he began writing about, and then befriended, Nathaniel Ayers a Juilliard-trained musician living with schizophrenia — and performing Beethoven — on the streets of L.A.

The story of Lopez’s friendship with Ayers, and Ayers’ journey from the streets to supportive housing, is chronicled in Lopez’s memoir. The book, in turn, inspired the feature film starring Jamie Foxx and Robert Downey, Jr. that was released in theaters nationwide on April 24.

The homeless men and women of Skid Row also opened the eyes of film director Joe Wright. In preparing for the making of the film version of The Soloist he took a tour of Skid Row with Lopez and visited a homeless shelter for people who have been diagnosed with mental illness. Wright decided he needed to get the homeless involved in the making of the film, he said in an interview with National Public Radio.

The director went back to the studio and told executives he wanted to include about 500 Skid Row residents in the production.

“Isn’t that what film is about – showing someone’s point of view that you might not have experienced before?” Wright asked.

An estimated 25 % of the nation’s homeless people live with severe mental illness, including such diagnoses as chronic depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders and severe personality disorders, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

At the Capitol Hill briefing Lopez stressed what he called a double tragedy: the fact that the mentally ill homeless were on the streets at all, and that society was not doing all that could be done to effectively reduce it.

“We know what works,” he declared, “permanent supportive housing.”

Such an approach has been undertaken in many cities in recent years, including New York, Philadelphia, Washington and Los Angeles. It is geared toward placing chronically homeless people, including those with mental illness in safe and stable homes, and providing them with the supportive services they need to remain housed.

Yet efforts have been hampered in some cases by neighborhood resistance to placements, funding and leadership gaps, and difficulties with providing long term supportive services, according to other panelists who joined Lopez at the briefing. In the District, 412 people are currently living in permanent supportive housing, but funding for placements for the coming fiscal year has been frozen due to the city’s budget deficit.

In Los Angeles, the permanent supportive housing approach has worked for the hero of The Soloist. Ayers has been at the same apartment every night for the last 3 years, Lopez said. Although not yet willing to take medication, Ayers is no longer without a place to call home.

Lopez was brought to Capitol Hill through an effort led by Participant Media, a production company associated with the film that partnered with a group of organizations that advocate for permanent supportive housing as the best way to reduce chronic homelessness. The organizations involved included The National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH), the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH), Project H.O.M.E., and HELP U.S.A. Their objective is to persuade Congress to act on three specific measures this year:

1) Pass the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act to reauthorize HUD’s McKinney-Vento assistance grants and make improvements in the original program that raise the priority for permanent housing and increase homelessness prevention resources.

2) Increase FY 2010 funding for McKinney-Vento homeless assistance grants to $2.2 billion – a level that would allow communities to provide a better mix of preventive activities, transitional housing, permanent housing and supportive services and fund 15,000 new units of supportive housing

3) Increase funding for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) homeless program services to provide for critical services related to health care, substance abuse, and mental health services.

While promoting common legislative and funding goals, panelists appearing with Lopez offered their own particular emphases.

Thomas Hameline, of New York-based HELP USA, a national non-profit organization that provides housing and a comprehensive menu of services to people in need, spoke about the progress his city had made in the last few years in reducing chronic homelessness via supportive housing initiatives. Hameline also highlighted the struggles of homeless veterans, and called for including veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan fighting in homeless prevention efforts.

“We do not want to reproduce the problems we experienced with Vietnam vets,” he cautioned. Hyacinth King, a resident at Philadelphia’s Project H.O.M.E. (Housing, Opportunities for Employment, Medical Care, Education), a community that focuses on permanent supportive housing and education, spoke about her struggle with schizophrenia.

“I was in college when I first heard voices and lost touch with reality,” she recounted. She finished her business administration degree at Temple University, but things got worse.

Eventually she ended up, as she put it, “living in my car or in a cardboard condo, and self-medicating with pills and alcohol because of the stress of homelessness and mental illness.”

Bob Carolla, the director of media relations for NAMI, recounted his own bouts with bipolar disorder. As a former congressional staffer himself, Carolla advised the audience that “Mental illness can strike anyone. I wasn’t immune to it and neither are you.”