Data collection by Gordon Chaffin; mapping by Peter Wood; writing by Eric Falquero

D.C.’s recent pilot program for housing some residents of homeless encampments and permanently closing several large encampments has sparked intense debate. Street Sense has covered these developments closely in numerous articles. But It can be equally helpful, to pull back and look at the bigger picture: Who can occupy public spaces — and how — is increasingly being called into question.

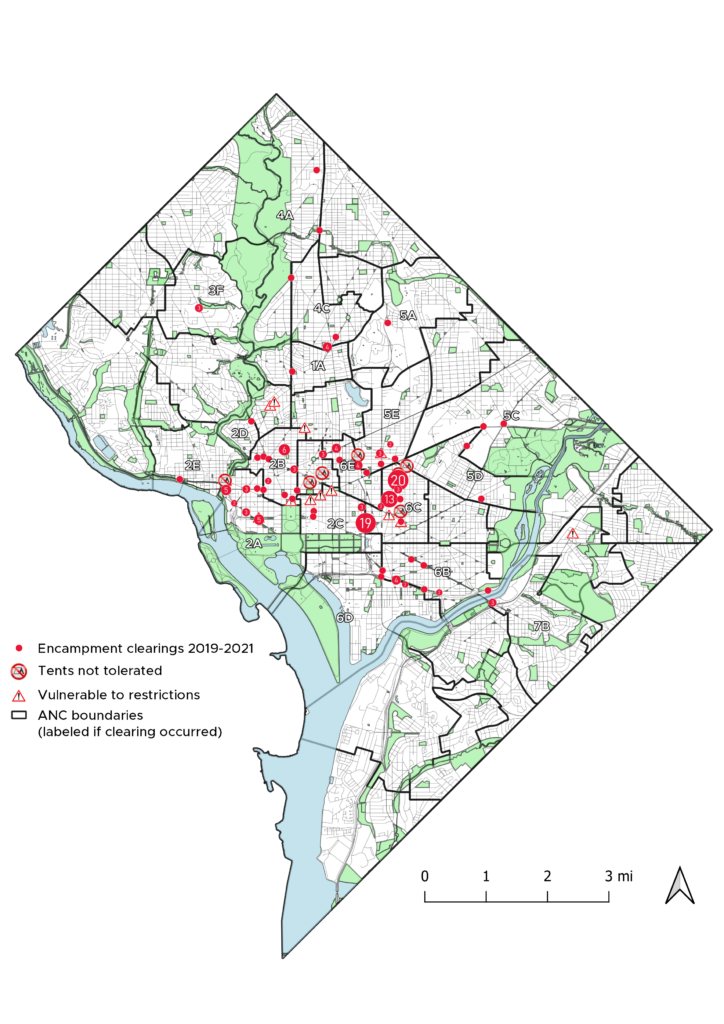

The “encampment clearing” dots on the map above show where “full cleanups” or “immediate dispositions” have been carried out by the District government in the past three years, accounting for pre-pandemic policy as well as more recent activity. There were 159 such actions, including one scheduled for Dec. 21.

- “Trash-only” cleanups or “self-resolved” cleanups were excluded. D.C. publishes annual reports documenting every instance when its encampment protocol was engaged in the previous year at https://dmhhs.dc.gov/page/encampments. A list of scheduled near-term cleanups is maintained on the same web page.

The “no” symbols, where tents are not tolerated, indicate where policy, physical barriers, or both prohibit use of tents.

- In some cases, the locations were restricted after an encampment clearing conducted on federal land by the National Park Service. No comprehensive data on NPS clearings is publicly available.

- The newly renovated Franklin Square Park is also included in this category due to an explicit no-camping decree in its code of conduct, the restriction of food distribution groups that wished to use the park to meet homeless participants, and round-the-clock security staff.

- All of these sites were newly restricted during the same 2019-2021 period as the encampment clearing data — except for one. A location in Foggy Bottom, on 27th Street NW, near the Whitehurst Freeway, was included because it has remained fenced off since it was closed in 2015. At the time, the Bowser administration was just developing its approach to encampments. At the time, D.C. Water said the area was fenced off because it was needed for cleanup and inspection of a portion of the sewer system that had to occur before the end of March 2016.

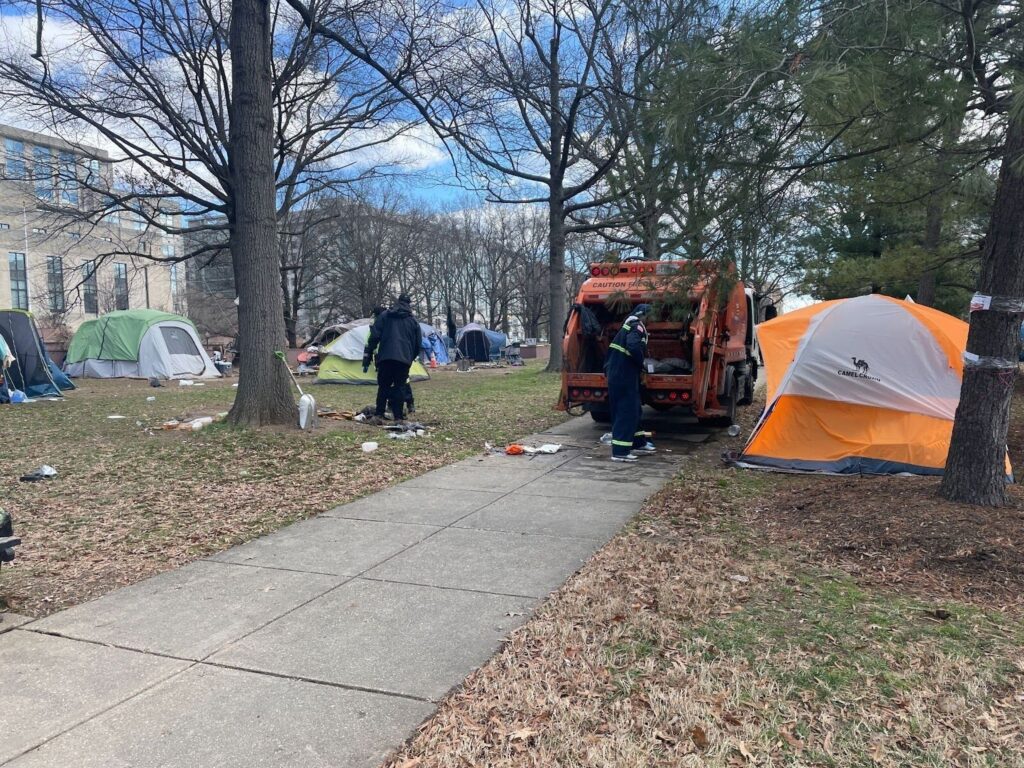

The average cost of an encampment clearing managed by D.C. government is unknown. This interagency effort, coordinated by the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services (DMHHS), typically includes multiple MPD officers, Department of Human Services and/or Department of Behavioral Health workers, and Department of Public Works personnel.

If each of the 153 clearings represented on this map cost $1,200 to execute — the lowest amount listed on a 2016 record DMHHS submitted to D.C. Council at the time — then the city would have spent $190,800 over the past three years. The outlier Foggy Bottom site from 2015 was included in this record. It cost taxpayers $132,334 to permanently remove people from that area. Fourteen were housed and $90,732.87 of that total cost went to the Department of Transportation, which was responsible for erecting the fence.

The “vulnerable to restrictions” category includes more unique instances, some where people could be forced to leave and others, where use of a space is allowed, but the space itself has been made uncomfortable or unusable.

- Neither this nor the “tents not tolerated” category are exhaustive lists. They include only what examples could be collected and verified. Send additional suggestions to [email protected].

- In one case, all of the benches were removed from the federal park and street adjacent to D.C.’s downtown day services center.

- Not all restrictions or actions are carried out by the government. In one case, an outdoor power outlet that was removed by the Reeve’s Center, then made available to the public again only to be covered in glue (seemingly by a private individual) to make it unusable.

Not visualized on this map is the use of hostile architecture. The Hoya reported on several examples in Ward 2 as part of the 2021 D.C. Homeless Crisis Reporting Project (https://dchomelesscrisis.press), including a project that had mapped hostile architecture across the metro region through 2018. When overlaid with this map of exclusion from public space, many of the previously documented hostile architecture locations align with where the D.C. government most often conducts encampment clearings.

While many factors influence where someone ends up living in the absence of safe housing — or when the government chooses to intervene — it is noteworthy that hardly any clearings were carried out east of the Anacostia River.