An ambitious local plan to end chronic homelessness is moving forward, despite a range of challenges, a district official told area social workers gathered for a recent conference at Gallaudet University.

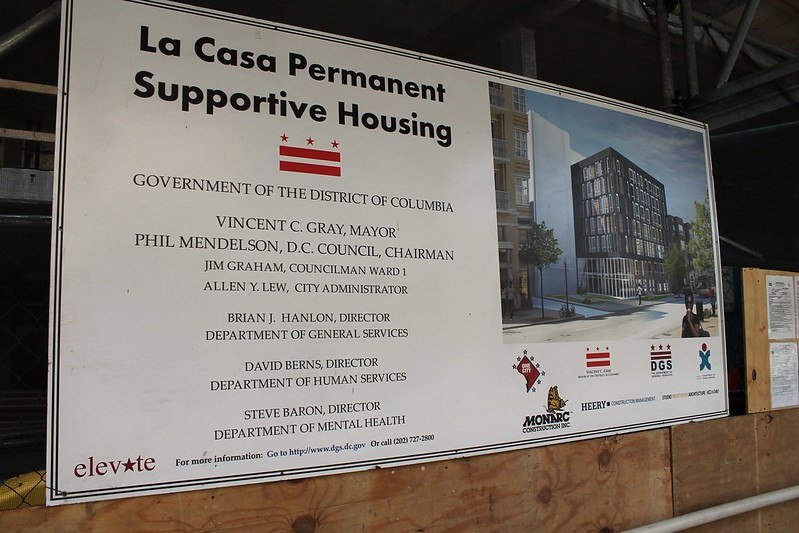

Fred Swan, Administrator for the Department of Human Service’s Family Services Administration, told the social workers, most of whom worked for city agencies or for local non-profits, that the District’s Permanent Supportive Housing program, which started at the end of the 2008 fiscal year, has so far housed 414 individuals and 1 family.

The economic slowdown has had an impact, Swan acknowledged.

“We did take some cuts this year in our program,” he said. However, Swan expressed hope for the future, noting that that the program’s goal for fiscal year 2009 is to house an additional 400 individuals and 80 families.

The District’s Permanent Supportive Housing program represents a “Housing First” approach to fighting homelessness. Similar programs are taking shape in jurisdictions across the country. The program aims to end long-term homelessness by moving vulnerable individuals and at-risk homeless families into permanent housing as rapidly as possible, and provide necessary social support along with that housing.

“You are more motivated to participate in other services when you have a stable place to call home,” Swan explained.

Such an approach constitutes a major shift away from the traditional emergency shelter system for helping the urban homeless, moving clients out of shelters and on to temporary transitional housing only when they show they are “housing ready” by staying sober, for example, or participating in a rehabilitation program.

“This was a bold aggressive move,” said Kelly Sweeny McShane, executive director of Community of Hope, one of the housing organizations working with the city on the new effort.

“It’s challenged us to think in a different way. It’s very much a learning process,” added McShane, who joined Swan in speaking at the conference. She noted that Community of Home, a family-focused service organization, had not yet placed a family in permanent supportive housing.

The reason that so few families have been housed, Swan explained, is that the family portion of the program only began in December. In addition to having started later, he added, the initial funding had been done using local funding sources that do not involve the delays often associated with federal funding.

“Local dollars allow us to move more people in faster,” Swan told the audience. “With federal dollars the process is different. Federal resources have higher documentation requirements.”

Most of the local funds had been used for housing single adult men and women by the time that families were being addressed. Their part of the program is relying mainly on federal funds.

Role of Case Managers

Swan, McShane, and Amanda Harris, of Pathways to Housing, another organization involved in the permanent supportive housing effort, all emphasized that social workers, and the expertise they provide, are crucial to the success of the program.

“Social workers are involved in all levels of the PSH program,” said Swan. He added that because “social workers understand how policy decisions are going to impact the clients and staff, they need to be involved in the policy decision process, too.”

The supportive housing program’s targets for clients-per-case manager are 15 single individuals per case manager, or 10 families per case manager. The program demands above average case management expertise, Swan conceded. Because the program is targeted to the most vulnerable of the homeless, clients often have mental health issues, perhaps accompanied by alcohol or drug dependency.

Besides working with clients to establish individual goals and service plans, case managers must serve as liaisons between the clients and their landlords, meeting with the landlords monthly to help iron out any concerns.

Harris explained that because supportive housing units are scattered across the various city wards, clients may find themselves in neighborhoods distant from the service sites – such as shelters and food kitchens – on which they had formerly depended, and around which they may have formed communities. So program case managers also must assist their clients’ social integration into the new communities where they now live.

In the case of homeless families there is the additional element of ensuring the safety and education of the children.

Finding the Most Vulnerable

In its efforts to identify the single men and women most in need of permanent supportive housing and associated services, the Department of Human Services sought the assistance of a New York-based non-profit, Common Ground, that helped pioneer the use of Housing First efforts in the U.S. for the most difficult cases – people who have spent years on the street, suffering from mental illness, addiction, chronic disease or other physical problems.

Common Ground has extensive experience canvassing people who live on the streets and do not use the shelter system, documenting that population and persuading them to apply for the program.

Working with Common Ground, the Department of Human Services developed an index for assigning priority to individuals and families for housing eligibility. Priority was based on vulnerability and the length of time the individual had been homeless. The District’s vulnerability index helps identify individuals who have been “street homeless” for more than six months, and either suffer from one or more of a number of serious medical conditions or are over 60 years old.

Swan noted that a key factor to identify the most vulnerable was a person’s use of emergency medical services.

For homeless families, the vulnerability index also includes domestic violence issues, the need for stable housing for children (to allow family reunification), and repeat episodes of homelessness.

McShane pointed out that almost all families seeking emergency shelter and housing assistance in D.C. go through one central intake site, the Virginia Williams Family Resource Center, where they are screened to determine eligibility for housing and other forms of assistance. She related that 350 families already had been surveyed for the 80 family housing units that are expected to become available this fiscal year.

Roughly 75% of the families that Community of Hope assists, Shane said, are headed by women. About 60% are dealing with depression or different kinds of trauma. Appropriate family housing is more difficult to locate than singles units, she said, because families often require two or three bedrooms.

Moving Forward

Swan outlined for the social workers how his department will be working with the eight organizations that have contracted to provide case management services to the program.

“We meet bi-weekly with all case managers,” Swan said, “and there are monthly meetings with the provider organizations.” He also pointed out that the city has a monitoring team that randomly checks on how the case management process is working.

He noted that the expansion of the program had one downside.

“Initially, no one thought this was for real. But once we started housing people, it really got everyone’s attention,” Swan said. Now that it is up and running, the program is beginning to attract people from other local jurisdictions and states, he added, noting that DC’s residence requirements tend not to be restrictive.

Right now, Swan admitted, the program defines success in terms of clients retaining their housing and developing a service plan, but his department is talking about developing a more formal evaluation component to the program.

The vulnerability survey will also require some tweaking, he admitted. It doesn’t account for severity of medical problems, only their existence. At first it was not a problem because the organizations working with the department knew who the chronically homeless and long-term shelter users were.

Now the department finds that some applicants understand that the more fragile they seem, the more likely they’ll be housed. So, he said, verification of information could become an issue.