Anthropologist recalls the secret world of the tunnel people in New York City

In the mid-1990s, almost a thousand homeless people were living along the unused tracks of New York City’s branch of Amtrak. Journalists from every major news source in New York went down into the tunnels to cover the story, but they only scratched the surface.

When anthropologist Teun Voeten first went down in the fall of 1994, he was so intrigued that he wanted to do a study on these underground societies. He lived with one group on the West Side of Manhattan for five months as a member of their community. He became such a part of that world that he had to remind people every now and then that he was a journalist, a participant observer, and had not had homelessness thrust upon him as everyone else had.

On a visit to Washington this fall, Voeten stopped by La Casa Community Center to share stories from his experiences underground.

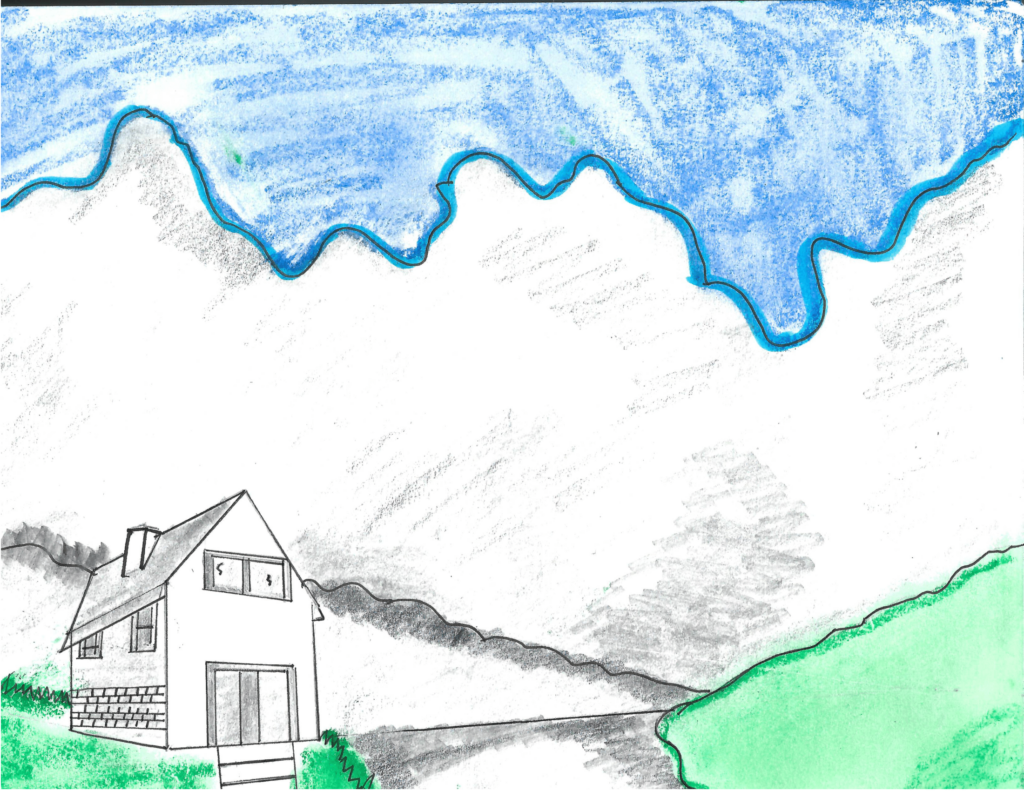

The tunnel where he stayed was not a deep, dark place as you might imagine. It was relatively close to the surface, and during the day light would pour in through a gap in the street above as well as through grates along the length of the tunnel. Because it was still underground, winters were cold but bearable. It was better than being on the streets. There were about forty people in the group Voeten was with, and within that most people formed smaller groups to protect and take care of each other.

Voeten claims he never felt threatened during his stay in the tunnels, but if a situation ever arose, there were always people to help. Even though people lived together, everyone had his or her own living space. Voeten’s best friend in the tunnels, Bernard, had a corner set up like a home, with different sections for sleeping and eating, and he even set up a kitchen area. Bernard loved to cook and he had pots and pans, cookbooks, herbs and spices, and a small fireplace to cook upon.

As Voeten describes it, the “tunnel people” had a real functioning society down there. They would each take turns cooking for the group, and they used plates and silverware and ate at a table just like anybody else.

“There were also a few rules I had to learn” Voeten said of his stay. “Simple stuff like ‘don’t be an asshole.’” Though it rarely happened, if any of their rules for peaceful coexistence were broken, that person would be beaten and possibly kicked out of the tunnels.

The “tunnel people,” as Voeten refers to the group, did not fit the stereotype that people commonly stick them with. They were too proud to beg, and most didn’t have welfare, so they had to work for their money. Most people did this by collecting cans. Bernard would get up every morning at five o’clock, make some grits and chamomile tea, and go out to collect cans at five-thirty. Many had made deals with landlords to collect the entire building’s recyclables. At five cents a can they could easily make around $60 a day.

They would then take the cans to one of a few nonprofit organizations in the area that redeemed an unlimited number of cans, because most supermarkets tried to turn them away with so many. There were also other ways to make money. In this particular group, several people sold books in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and others would gather things that people had put out as trash, such as bicycles, fix them up and resell them.

Still, this underground world was not perfect. Drugs were a big problem in the tunnels, especially crack and cocaine. According to one study done in 1994 about 56 percent of the tunnel people were drug users. Voeten said that drugs helped kill the pain, and that “if you have nothing left to lose, it’s very easy to go down.”

He even admits that he did cocaine twice during those five months as a way of releasing aggravation, and that if he didn’t have a wife and family back home to think about it would have been extremely hard to resist its addictive power.

Some people got so desperate that they had to go through middlemen, who would buy cans at half the price in the middle of the night, when no one else would take them. That’s also why Voeten didn’t give large amounts of money to them while he was in the tunnel. He’d give small gifts every now and then, but if he gave people money he knew many of them would just turn around and use it for drugs.

After his five-month stay in the tunnels, Voeten left and went back to his family, and he wrote a book about his time there, called Tunnel People. As he was writing it, he got some disturbing news: Amtrak was evacuating everyone in the tunnels. All the journalists had made them widely known, and Amtrak was liable for any accidents that occurred because it was on their property. Various homeless organizations such as Project Renewal and the Coalition for the Homeless tried to help settle the people in the tunnels.

According to Voeten, about 70 percent of the people accepted housing, and 50 percent are doing well to this day. Most of them are healthy, because they walked everywhere and got plenty of exercise, and they keep that habit still. Because of the connections they made collecting cans, many of them continued to do the job after they had formal housing.

Voeten visits his friends from the tunnels frequently, and most of them have adjusted well in the fourteen years since they’ve been homeless. If you saw them on the street you would have no indication that they were of the legendary “tunnel people.” But even if the people have changed, the story will forever be a part of history for those it reaches.