This article was first published by DCist on April 15.

The best place to get to know Maurice Abbey-Bey was in the van.

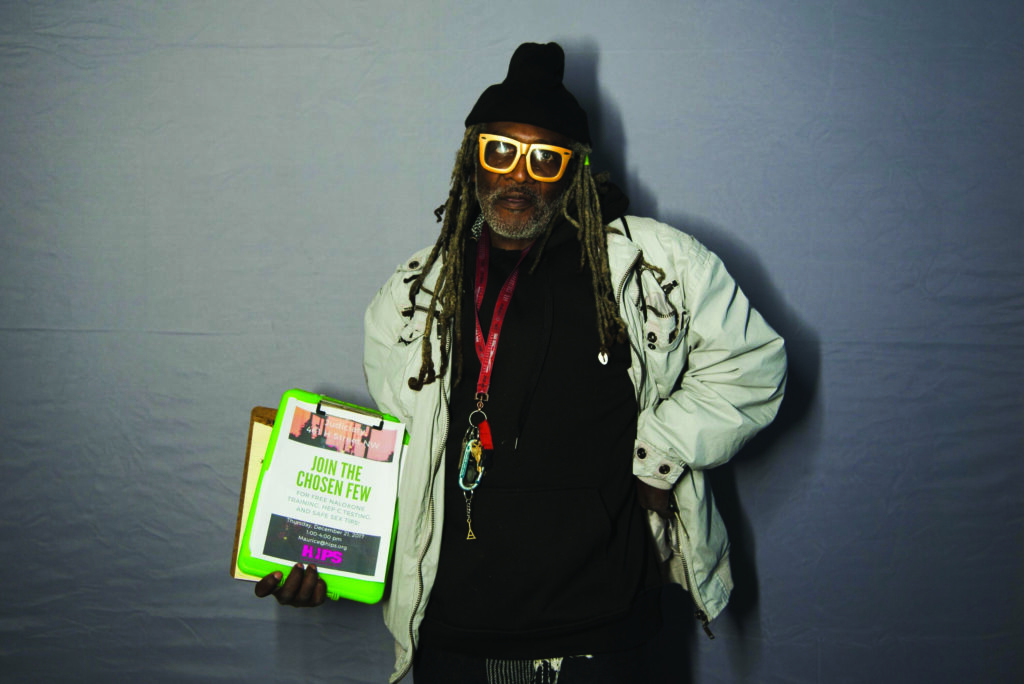

Most days, he roamed around the streets of D.C. in a white outreach van belonging to the harm-reduction organization HIPS, handing out clean needles and condoms to residents who need them and administering life-saving Narcan to people experiencing drug overdoses. Known to his colleagues and friends as the “Jesus of the streets,” or simply “Moe,” the D.C. native led an incredible life, one that took him from the dark pits of opioid addiction to the forefront of drug policy changes in the city.

Abbey-Bey died on April 5 after a battle with leukemia, according to his family, and leaves behind his wife and work partner, Charmaine Sauls, three biological sisters, and 17 nieces and nephews. He was 64 years old.

Friends, family, and coworkers describe Abbey-Bey as an unmatched force of nature in D.C. He changed the lives of just about every person he met — and he met with everyone he could, from people experiencing the worst conditions on the streets to high-profile politicians, spreading his gospel of ending drug-related deaths across the U.S. (Senator Bernie Sanders highlighted Abbey-Bey’s work for International Overdose Awareness Day.)

WAMU once spent a day with Abbey-Bey as he handed out syringes and explained the dangers drug users face when injecting with used needles. He described the horrific things he’d seen, like people using contaminated water to cook heroin.

As a former heroin user, Abbey-Bey knew these stories personally. A family member gave him his first shot at 12 years old, he once said. He was incarcerated for about 30 years on drug charges, but when he got out of prison in 2003, he didn’t let those experiences define him. He got clean at 45 and empowered others by sharing his journey, promoting safe use and helping others overcome addiction. With his personal story in tow, he helped create the Chosen Few, a HIPS initiative focused on research, peer-to-peer education, and supporting those who have been most impacted by the War on Drugs.

“Everybody knew Moe,” said Alexandra Bradley, the HIPS outreach manager. “Everybody knew that if you wanted a conversation with Moe, you got in the van. That was where he did his thinking, it’s where he told all his stories. He used to go out with staff and interns to teach them and take them under his wing.”

Bradley was a volunteer in 2015 when she met Abbey-Bey, who was supposed to interview her for a full-time job. She was on the fence about it, but Abbey-Bey showed up to her house in the van, told her to hop in, and proceeded to share words of wisdom and encouragement. The heart-to-heart ultimately convinced Bradley to join the staff.

“He had really big dreams, thoughts, and ideas,” Bradley said. “He was never afraid. If anybody walked up to him with a microphone, he was always ready. He lived and breathed harm reduction, and it was beautiful to watch.

Those closest to Abbey-Bey describe him as a gifted orator and an open book. But he was also a fighter who had a direct impact on D.C. policy, not an easy feat in a city where Congress has to approve its laws.

Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen remembers a committee hearing in 2018 when Abbey-Bey came in to testify about fentanyl tests, which help users detect whether drugs have been laced with potent additives that can cause users to overdose quickly.

The strips had only recently been legalized in D.C. on a temporary basis. As was the case with most drug paraphernalia, the ban on their use disproportionately affected the Black community — over the past decade, roughly 80% of the paraphernalia-related arrests in D.C. have been of Black residents, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. (The D.C. Council went on to permanently legalize their use in 2018.)

At the hearing, Abbey-Bey reached into a bag and took out what appeared to be pieces of aluminum foil.

“I remember turning to my staff, and I was like, ‘Is he about to test for fentanyl right now?’ and my staff was like, ‘I think he is. Fentanyl is illegal, should we stop him?’” Allen recalls. “I said, ‘No, this is incredibly powerful and real. Let it play out.’”

Allen and the rest of the committee leaned forward in awe as they discovered that Abbey-Bey had pulled out a row of used heroin cookers he collected himself from across the city. Testing them all on the spot, each one came back positive for fentanyl.

Allen said Abbey-Bey’s advocacy directly led to the permanent decriminalization of fentanyl testing strips in 2018 and the decriminalization of drug paraphernalia in 2020. Abbey-Bey also sparked conversations about the possibility of opening safe use sites in D.C., places where people can use pre-obtained drugs under the supervision of trained staff.

With Abbey-Bey’s help, HIPS partnered with D.C. Health in 2016 to start giving clients naloxone (or Narcan), to reverse opioid overdoses.

“When we talk about policy and legislation, sometimes it’s hard to make it accessible and real,” Allen said. “One of the real strengths that [Abbey-Bey] had was to communicate effectively and normalize the conversation around what might otherwise be to policymakers an intimidating change.”

The passionate advocate was also a family man. Reese Johnson, Abbey-Bey’s niece, said he managed to be present, even while incarcerated.

“We wrote each other throughout the years when I was old enough to write,” Johnson said. “He would always send gifts and pictures, all types of unique things. I couldn’t understand how he was able to do so much in prison. But I got birthday cards and birthday calls. He made it known who Uncle Maurice was even if I was never going to be able to meet him in person.”

But meet in person they did. Johnson said when Abbey-Bey left prison and started making his mark on the city, he never bragged about his accomplishments; but he never had to, as his work spoke for itself. He began volunteering with HIPS in 2012, and just a year later, became a secondary exchange peer educator. As he gained experience in the field, HIPS tapped him to become the organization’s full-time syringe exchange specialist in 2014.

HIPS executive director Cyndee Clay said Abbey-Bey’s work opened doors for the H Street-based organization and paved the way for its workers and volunteers going forward.

“Moe wasn’t the first person to help us create inroads with the community, but he really had a passion and was a leader in making sure those tough conversations were being had,” Clay said. “He was dedicated to being out there and saving lives.”

The work Abbey-Bey helped start has only picked up. Due in part to the loneliness and chaos sown by the pandemic, 2020 became the deadliest year in overdose deaths in D.C. as cases also surged nationally. Clay said that, over the past year, requests for HIPS’s mobile services have nearly tripled. And despite having to scale back some of its operations at the height of the pandemic, the outreach team distributed over half a million unused syringes to people in need just last year.

Even in his absence, Abbey-Bey will continue to make an impact. Aug.31 is International Overdose Awareness Day, and HIPS staffers say they will celebrate it in honor of Moe.

And, most fittingly, he will still be in the van — well, technically, he’ll be on two of them.

“We’re back on the streets this week, and we’ve got this beautiful memorial to Moe that we’ve put on the side of our vans,” Clay said, “Because he’s always going to be out there with us.”