This book will be an eye-opener for anyone who thought slavery ended with the Emancipation Proclamation.

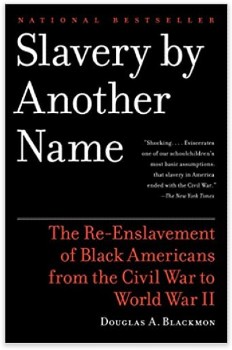

It didn’t. It continued on by other names, including involuntary servitude and peonage, well into the 1930s, and the sordid story is reported in telling detail and lucid writing by Douglas A. Blackmon in “Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II” (Anchor 2009).

Blackmon tells with horrific examples how recently freed blacks were rounded up and arrested for violating many hastily enacted laws, especially vagrancy ordinances – with vagrancy defined as not being able to prove at any given moment that one is employed – a situation not uncommon for the thousands of blacks just recently unchained by their white owners.

He cites the case of a 22-year-old arrested for vagrancy, found guilty, given 30 days of hard labor, plus required to pay fees to the sheriff, his deputy, the court clerk and witnesses. When he couldn’t pay the fine, a local steel company agent turned up, fortuitously, to pay it, and the “vagrant” was turned over to the company to pay back his fine, which turned out to be nearly a year of hard labor.

Blackmon says the incident was common in the post emancipation South.

The vagrancy and other capricious ordinances were enacted because the whites running the governments were baffled as to what to do with the freed slaves who were wandering from town to town looking for work and food.

“Indentured servitude” followed, the result of a conspiracy between local officials and businessmen. In many cases, the only income the local officials got was through their “leasing” black convicts to the local businesses, who then used this “pool” of blacks as all but free labor (as in slavery), as during slavery, to run, at first, plantations and then later as industry came to the South, coal and iron mines and steel mills.

Blackmon writes that “These bulging slave centers became a primary weapon of suppression of black aspirations.

Where mob violence or the Ku Klux Klan terrorized black citizens periodically, the return of forced labor as a fixture in black life ground pervasively into the daily lives of far more African Americans.”

He says, “hardly a year after the end of the war, in 1866, Alabama Governor Robert M. Patten, in return for the total sum of $5, leased for six years his state’s 374 prisoners to a company calling itself “‘Smith and McMillen.”

The company was a sham, and actually was controlled by the Alabama and Chattanooga Railroad. And the example is not unique.

The conditions under which the indentured prisoners worked and lived were dire: they were often chained as they worked, and were fed sparingly, and at night were kept, chained, in communal barracks, without the necessities of running water and toilets. There were whippings and other grisly punishments.

Blackmon found out that in the first two years that Alabama leased its prisoners, nearly 20% of them died; in next year, the mortality rose to 35%, in the fourth year nearly 45% died.

Faced with this resurgent slavery and little justice from the southern courts, some blacks and their few white advocates, sought help from Washington, asking for grand jury investigations.

But they got little help. In one case cited, a federal grand jury convicted two whites for “peonage,” but an appeal was made to Washington for a pardon, and it was granted by President Theodore Roosevelt.

President Woodrow Wilson, in contrast to his “Wilsonian” reputation, was little better, Blackmon finds,

The end of this new slavery came in an ironic way, with World War II, Blackmon concludes.

“President Franklin Roosevelt,” Blackmon writes, “instinctively knew the second-class citizenship and violence imposed upon African Americans would be exploited by the enemies of the United States.”

He issued orders that allegations of slavery that in the past had been handled by local, and mostly antiblack jurisdictions, would henceforth be prosecuted as a violation of the anti-slavery 13th amendment to the Constitution.

“It was a strange irony,” Blackmon concludes, “that seventy-four years of hollow emancipation, the final delivery of African Americans from overt slavery and from the quiet complicity of the federal government in their servitude was precipitated only in response to the horrors perpetrated by an enemy country against its own despised minority.”