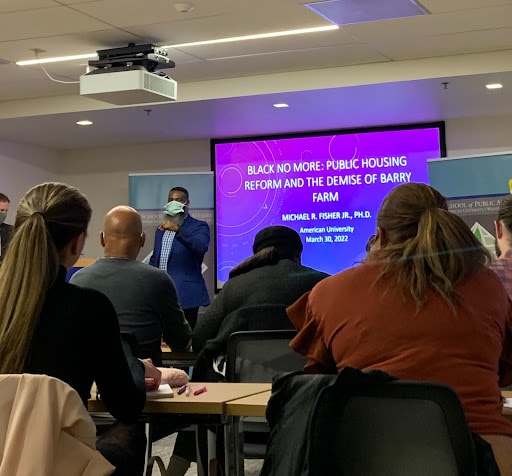

The Metropolitan Policy Center at American University hosted a public lecture on March 30 about the Barry Farm public housing development. Titled “Black No More: Public Housing Reform and the Demise of Barry Farm,” the lecture was delivered by Dr. Michael R. Fisher, an assistant professor of African American Studies at San Jose State University.

“The story of Barry Farm illustrates the adverse effect of public housing reform on Black communities who live in high poverty neighborhoods,” Fisher said.

From the mid-20th century to the present, public housing reform has been a historic catalyst for the demise of low-income communities, he said. His presentation focused specifically on the adverse impacts of D.C.’s efforts to turn Barry Farm into a mixed-income neighborhood on residents.

“When I say ‘demise,’ I’m talking about the breaking up and scattering of the community members in the neighborhood and the disruption of their social networks,” Fisher said.

Barry Farm residents were displaced under the New Communities Initiative (NCI), a District government program that began in 2005. The NCI is designed to replace public housing developments that have “concentrated poverty, high crime, and economic segregation” with “vibrant, mixed-income communities,” according to the Deputy Mayor’s Office for Planning and Economic Development.

The relocation of Barry Farm tenants began in 2012. Since then, the city forced hundreds of families to relocate their homes in order to make way for demolition. Residents have accused the D.C. Housing Authority (DCHA) of using intimidation tactics to get them to relocate.

Through the NCI, Barry Farm’s original 444 public housing units are planned to be replaced by 1,100 mixed-income residential units.

In 2006, the D.C. Council approved the Barry Farm Redevelopment Plan. Since then, progress on the redevelopment project has been glacial.

“In the 17 years since the initial planned redevelopment of Barry Farm, the city has produced no new housing of any sort, and only one new building in the neighborhood, the Barry Farm recreational center which opened in 2013,” Fisher said.

The four guiding principles of the NCI are ensuring zero net loss of affordable housing; giving tenants the opportunity to remain during redevelopment or returg; creating mixed-income housing; and building new housing prior to demolition in order to minimize displacement.

However, the city abandoned those principles as it progressed through Barry Farm’s redevelopment, Fisher said.

By the time DCHA received approval to begin demolition of Barry Farm in 2017, the city had already reneged on its core promises, he said.

DCHA announced in December 2016 that the build-first approach was cost-prohibitive for Barry Farm.

Furthermore, despite its claims to the contrary, DCHA also broke its promise to ensure no net loss of affordable housing, Fisher said. There were originally 444 total public housing units in Barry Farm, but the redevelopment plan only called for 344 new units. The remaining 100 units would be spread throughout other developments across the city.

In April 2018, when the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled in favor of a lawsuit filed against the city by the Barry Farm Tenants and Allies Association, it agreed with the plaintiffs that there would be a net loss of 100 units under the redevelopment plan.

In addition, the city’s one-for-one housing unit replacement principle does not consider the mix of various unit sizes, which would lead to the net loss of housing units available for large families, Fisher said. Analysts projected that the redevelopment of Barry Farm would net displace over 150 families, he said.

The city also violated its promise to honor tenants’ right to return after the redevelopment of Barry Farm, Fisher said. Strict screening standards often prevent the return of public housing tenants to a redeveloped property, he said.

The affordability of new units is a further impediment to the ability of Barry Farms tenants to return. Of Barry Farm’s original 444 public housing units, only 380 of the newly built units are “meant for extremely low-income households.”

Advocates for redeveloping high-poverty neighborhoods into communities where people with a broad range of incomes live argue that doing so can expand the social networks of low-income earners, Fisher said.

However, this has not been the experience of Barry Farm tenants, he said. He pointed to the experience of a former tenant who moved to the mixed-income community of Deanwood after being evicted from Barry Farm. Shortly after moving to this new neighborhood, the tenant reported feeling deeply isolated from her new neighbors. She did not feel like she belonged in the community. Her experience mirrors that of many other people who were forced to suddenly relocate to mixed-income neighborhoods, Fisher said.