Sharron Brown, a 61-year-old unsheltered resident of Virginia and 25th street encampment, has had to call police on multiple occasions to break up fights or ward off intruders near her tent.

But Brown, who said she has been experiencing homelessness for over a year, said police only give warnings and oftentimes let hostile encampment intruders leave freely.

“It’s like you want to wait until bloodshed until someone seriously gets hurt,” she said.

Last month, the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) arrested and charged a man with first-degree murder for the suspected shooting of five men experiencing homelessness in New York and D.C., which killed two people. The murders are part of a wave of violent acts against people who are experiencing homelessness, including stabbings and sexual assault. Many attacks go unreported.

Brown said if the police departments have available funds, they should add a security guard to watch over the encampment to break up brawls and prevent people from becoming “rowdy” in the afternoons or evenings.

“It would be a lot easier if you just have someone here that has a uniform on, [encampment residents will] respect them,” Brown said.

More than half a dozen unsheltered D.C. residents and homeless rights advocates recognize the dangers that come with living in encampments, but are torn over the degree to which the police should engage with homeless communities for safety concerns, encampment cleanups, mental-health crisis responses and outreach efforts.

Homeless encampments, or any temporary place of abode in structures such as tents, automobiles, or house trailers on public or private property D.C. are illegal.

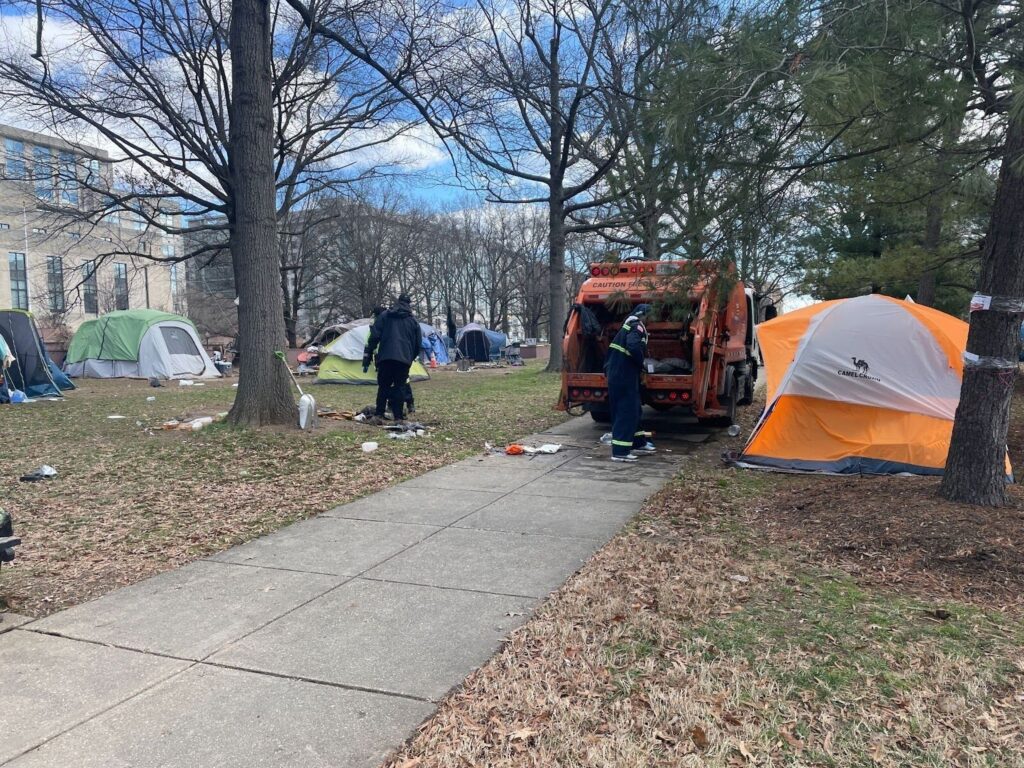

The mayor’s office said there are public health and safety risk factors related to the presence of encampments, including the blocking of major pedestrian thoroughfares and trash buildup.

The Mayor’s office enlists several different agencies to coordinate encampment cleanups, with each one performing a specific function during cleanups. Cleanups are supposed to offer various support services to individuals intended to help better stabilize their living condition, while also addressing immediate public health and safety issues on the site. The Metropolitan Police Department, or MPD, is responsible for providing security during encampment cleanups.

But homeless advocates said MPD involvement with cleanups comes with the threat of violence, as they will forcefully remove residents if they do not comply with D.C. agencies.

Jesse Rabinowitz, a homeless rights advocate and senior manager for policy and advocacy at Miriam’s Kitchen, said that the presence of about 30 police officers at the New Jersey and O park encampment eviction that occurred on Dec. 2, 2021, was an “egregious show of force” and obstructed access to the encampment.

“[They] did nothing to end homelessness, and actually prevented outreach workers, but more importantly, prevented people living in the encampment from getting in and out of the encampment,” Rabinowitz said in an interview with Street Sense Media.

In police departments across the United States, officers are sometimes tasked with conducting outreach to homeless communities and to provide unsheltered residents with resources that can connect them to housing, as well as other forms of assistance.

The San Francisco Police Department has a special unit that provides “targeted street outreach” to the city’s homeless population. In 2017, the Seattle Police Department also launched a Navigation Team that pairs outreach workers with the Seattle Police to connect unsheltered residents in the city to permanent housing. The Boston Police Department has a street outreach team that offers “help, support and services” to homeless individuals and individuals suffering from substance abuse.

Last December, MPD launched the First District’s Homeless Outreach Program and Empowerment (HOPE) initiative. The initiative’s mission is to “work proactively with our homeless community and partnering organizations to assess their needs and liaison services,” Brianna Burch, an MPD spokesperson, said.

Providing homeless outreach is not a function served exclusively by the first district within MPD. MPD also has foot patrol officers assigned to homeless outreach units in all seven police districts, Burch said.

Advocates argue that outreach efforts should be limited to case managers, social workers and public health professionals – and should exclude armed police officers.

Natacia Knapper, managing organizer with the American Civil Liberties Union of D.C., said those who engage with the homeless community in street outreach should be professionals trained in trauma-informed practices who have built trust with their unhoused neighbors.

The police are not equipped to do that work, Knapper said.

Last month, Mayor Muriel Bowser proposed the use of $30 million to hire, recruit and retain 4,000 new MPD officers in her fiscal 2023 budget.

Advocates, however, said that because the police have historically played a role in causing harm and trauma to individuals experiencing homelessness in crisis response scenarios, the mere presence of a police officer can be an automatic trigger for unsheltered residents.

“Even if [the police] are doing their absolute best, it’s not enough because they’re still causing trauma, just by being a weapon-carrying human being that is approaching very vulnerable, scared and traumatized people,” Knapper said.

In a 2017 press release, MPD said officers tasked with conducting homeless outreach are trained “on issues of homelessness including resources for individuals experiencing homelessness, the rights of homeless individuals, and skills in dealing with the mentally ill.”

But having police officers undergo training before engaging with unsheltered communities is not the right solution, Knapper said.

Instead, the city should invest more money and resources into professionals outside of the police force who are specifically dedicated to providing trauma-informed care and resources to unhoused individuals, “rather than training people in a different agency that is completely disconnected from that work,” they said.

That’s a sentiment echoed by Rabinowitz.

“Our caseworkers [at Miriam’s Kitchen], our street outreach workers, have significantly more training [than the police] in working with this specific population. It’s their entire job, not an added training,” Rabinowitz said.

In fact, having police officers conduct homeless outreach may actually cause more harm to unsheltered individuals, especially when those individuals are undergoing a mental health crisis, advocates say.

In July 2020, Street Sense Media investigated the deeper systemic problems behind the wrongful arrest of a Black man who was handcuffed and shackled at the ankles at the Black Lives Matter Plaza in D.C. while experiencing a mental health episode. The arrested individual, referred to by the nickname “D,” reportedly lived with schizophrenia and homelessness.

In a video of the incident, there were attempts by a volunteer medic to calm the man l down and deescalate the situation. These efforts were allegedly repeatedly rejected by MPD officers.

A 2018 audit report that analyzed how the D.C. Department of Behavioral Health interacts with the criminal justice system said, “the District does not yet have robust programs and policies in place for police officers to identify individuals with mental illness and divert them from the criminal justice system to behavioral health services in lieu of arrest.”

“The more entry points we create between the police and our homeless community, we’re going to see an increase in unhoused people being incarcerated,” Knapper said.

That’s because the tools that police officers have when reacting to unsheltered individuals in crisis are limited.

“Without access to appropriate alternatives, officers are often left with a set of poor choices: leave people in potentially harmful situations, bring them to hospital emergency departments, or arrest them,” a 2019 report by the Council of State Governments Justice Center said.

However, unsheltered District residents think police officers could also provide an extra layer of protection in encampments.

Jill, who declined to give her last name, moved from her hometown of Baltimore to an encampment site in D.C. around Christmas last year, the exact location of which is omitted for her safety.

She said she would feel safer with a greater police presence in her encampment only if that presence was used to protect vulnerable individuals.

“I would [feel safer], if they’re doing it to protect the community and protect people individually,” she said. “I need them. I need them to be present, I need them to do their job.”

Women who are unsheltered experience sexual assault, harrassment and violence at “enormously high” levels, according to the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence.

Jill said there is a limit to the amount of safety that a police officer patrolling an encampment could provide to its residents. Their time on duty is temporary and the dangers of living unsheltered persist after the police have left an encampment.

“But you gotta realize, you are on the streets,” she said. “When [the police officer] leaves, somebody might kill you.”