For three years, Chelsea Maggi would walk down a foot trail from the Fletcher’s Cove Boathouse to visit her father.

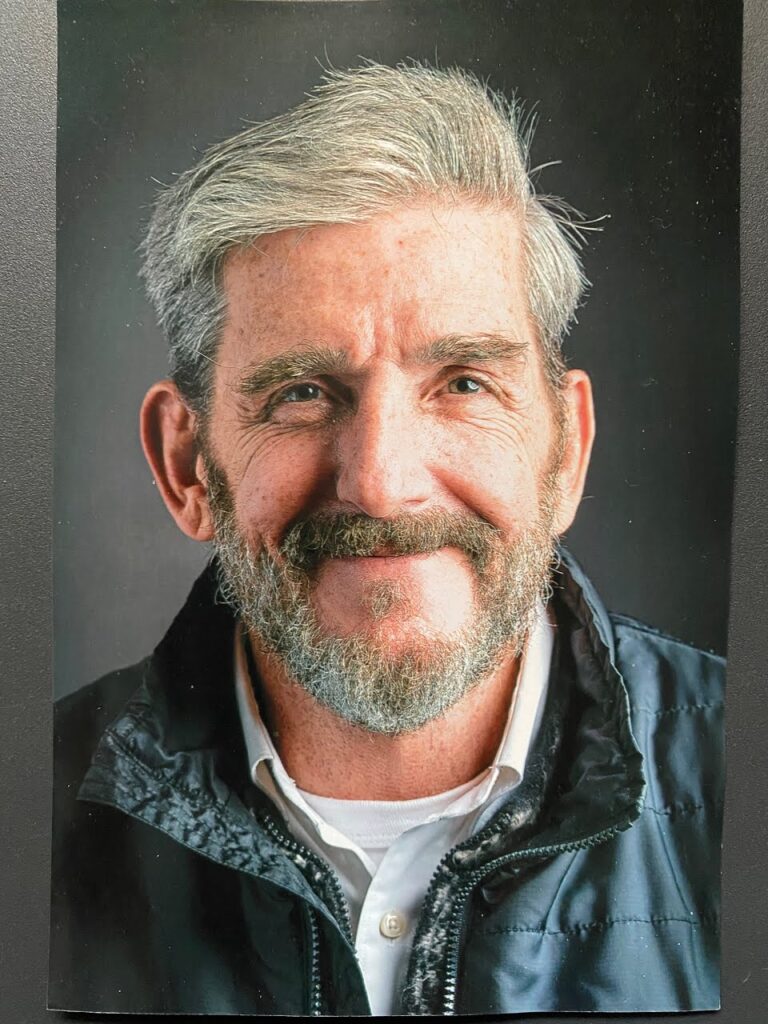

Her father, William “Bill” Maggi, lived in a tent by the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal in Washington, D.C., close to the 9th mile marker on the Capital Crescent Trail. While experiencing homelessness, his daughters say he liked to be well dressed and as clean and hygienic as possible. He would frequently visit his eldest daughter Nicole’s house to get a haircut.

Maggi passed away in his tent on the morning of Jan. 19. He was 58 years old.

A loving, complicated man

His daughters described Maggi as a force of personality: an intelligent and resourceful man who was extremely fond of them. Having begun experiencing homelessness since he was 14, he would travel from Washington, D.C., to other parts of the country, last playing poker in Las Vegas before returning to the District.

“My dad was warm. He was friendly, he was hilarious, a great storyteller, he would draw you in with great magnetics,” Chelsea said. At the same time, she said he could be fierce. “He was a maverick, a vagabond, you didn’t want to mess with him.”

Chelsea saw him twice a week these past three years, when she started to work more frequently in the D.C. Area. She talked to him by the canal and helped him decorate his tent. He would also sometimes come into her workplace to hang out and talk.

All three adult sisters noted that Maggi was well-read and constantly sought to learn more information about anything. “He always had an answer to any question I wanted to ask,” Nicole said.

Maggi began living on the streets when he was 14. The daughters cite his intensely abusive father and neglectful mother, and his family’s lack of understanding of his bipolar disorder, as reasons that led him to get kicked out of the house that young.

Maggi made a significant impression on the Dupont Circle community as well. Carolyn Fischer worked in the area as a legal editor for the Environmental Law Institute in the ‘90s and would hang out with bike messengers at the park within the traffic circle. On an average night during this decade, Fischer said about 150 bike messengers would hang out at this spot, talking, eating and entertaining themselves. They were especially friendly with Maggi, who enraptured their attention with his personality.

She recalled that she was throwing a baseball while wearing a sundress one day and Maggi, who was there, was surprised at her form. He approached Fischer to compliment how well she threw.

Fischer continued to hang out with the bike messengers, one of whom she married. She and her husband, then her boyfriend, continued to hang out with Maggi at the park and by the river whenever he lived there periodically for the past 30 years. She felt like he was her big brother.

“He was the kind of guy who could sell you the Brooklyn Bridge,” Fischer said. “It was like he was always performing. He was a great entertainer.” She said Maggi was a great singer, and he and Fischer’s husband would come up with lyrics on the spot.

She also witnessed his boldness. Once when they were at a concert and a drunk man came on stage and began badly singing, Maggi climbed up and punched him. “It’s actually video-taped, and you can hear the crowd cheering ‘Bill! Bill!’,” Fischer said fondly.

“And from day one, he talked about his daughters,” Fischer said. “Oh my god, he was just in love with his daughters.”.

Maggi separated from his daughters’ mother while they were young. When Nicole was 14, Maggi became more and more present in their lives. His second daughter from the same mother, Brooke, was insistent throughout her childhood on staying connected with Maggi, despite his wandering.

“I would constantly track him down and force him to be in my life, because I wanted a dad so bad,” Brooke said.

She described a more contentious, push-and-pull relationship with Maggi than the rest of her sisters. They would be close for a few years, then an incident would occur and Maggi would be physically violent toward her. Brooke said she was the only daughter he was violent toward. She said he was also violent toward her mother. The father and daughter would not speak for a few years, then one or the other would reach out and they would always re-establish their relationship.

The last time they were in good graces with one another, Brooke hosted Maggi in her home in Baltimore for six months in 2017. That was right before the last three years he spent in a tent in the District. Brooke said she managed to have a Christmas with Maggi, her mother, and her sisters that year — something she said was “magical,” as she had never experienced that before.

“But unfortunately my dad, when things were too comfortable for him, he always found a way to sabotage it,” Brooke said. At the time, she was helping Maggi get a job and housing. But he got increasingly agitated and found ways to show his frustration. In March 2018, an incident escalated to the point that she called the police on him. “I did not want that kind of behavior in front of my kid,” Brooke said. Maggi was escorted out of her home.

Brooke hadn’t seen Maggi since. He refused to talk to her.

“I hate that this is the memory I have of him now that he’s dead,” Brooke said. She believes his violence was a product of being “institutionalized to the streets,” needing to be brutal to survive.

Brooke and Nicole said part of the reason Maggi continued to experience homelessness was because any wages he earned were garnished for child support. He took all kinds of odd jobs as a limousine driver, a cook and more, and began pursuing a possible career as a poker player.

“Between prisons and hospitals and trying to find work and trying to find a place to live, he wasn’t always accepted,” Nicole said. The sisters approached their mother to stop requesting child support, but she refused.

Even with all his troubles, all three daughters and Fischer praised Maggi’s intellect, resourcefulness, and ingenuity. Chelsea proudly pointed out that he was an extra in “Forrest Gump.”

“He should have done so much better at life than he did,” Fischer said.

Disputed cause of death

In the summer of 2020 Maggi had a heart attack.

After the event Maggi told his daughters Nicole and Chelsea and swore them to secrecy. Six months later he passed away in his tent. Before his death, Maggi started taking care of a kid, Franco, who suffered from schizophrenia and had a badly broken leg. Both Maggi and Franco shared a tent on Jan. 19. In the morning, Franco woke up and briefly left the tent.

“He came back and saw that my dad was still asleep. He tried to wake him up and realized he passed away. He then called the police,” Chelsea said.

At the time, not knowing about his heart attack, rumors circulated among the community that he likely died from propane inhalation from a heater inside the tent. Nicole, Brooke and Chelsea all vehemently deny that as a possibility.

“My father was the ultimate survivalist. I tell you, there is no way, after a lifetime on the street, he died of carbon monoxide poisoning from a little heater in his tent,” Chelsea said. The sisters also point out that Franco slept in the tent as well throughout the night, and did not die. Nothing in the police report related to Maggi’s death mentions propane.

The sisters believe it might have been a heart attack that took Maggi. They are looking into foul play and natural causes of death other than propane inhalation, and are still waiting for a toxicology report. MPD declined Street Sense Media’s request for more information, as it is still an active investigation. The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner told Street Sense Media that the cause and manner of Maggi’s death are not yet determined. His case is still pending.

All three sisters interviewed for this article believe MPD did not care about their father’s death and were offended that a criminal investigation was not immediately opened.

“The fact that my dad passed away and they immediately write it off without any cause of death, that they’re just gonna immediately assume it was natural causes…you’re allowing people to slip through your fingers,” Nicole said.

Because of the pandemic, the three daughters could not visit their father’s body at the coroner’s office. Nicole said they had to pay extra money to send his body to a funeral home to see him one more time.

Maggi was working with a case manager with Miriam’s Kitchen and had received a housing subsidy. He was matched with an apartment a week before his death, waiting to get his keys. Chelsea said he was due to move in a few weeks.

Nicole points at the lack of resources and slow processing of housing applications that made it harder for Maggi to get through hypothermia season, even during a pandemic.

“He didn’t have access to the medical care that he needed, or a stable living environment,” Nicole said. “He got short-changed either way.”

“It would have been the first time in his life where I’d see him with a roof over his head,” Chelsea said.

Nicole believes that if there were more medical and psychological institutions in place to care for people experiencing homelessness, her father would still be here.

“Regardless of whether somebody did it to him or he died on his own, the system failed him,” she said.