He used to sleep outside a furniture store up on Wisconsin Avenue. It was right down the street from the gentlemen’s club that let him earn money as an unofficial doorman, where he’d once been handed a fistful of cash by a very drunk Harrison Ford. Plus, there was an exterior outlet he could plug his radio into.

He would lie awake at night, peering through the glass into the brightly lit showroom, with its queen beds, overstuffed sofas and ornately carved wooden dining tables. The showroom was set up like someone was living there, so the customers could imagine this piece or that piece in their homes. As he gazed through the glass, it became his home; his front room, his dining room, his bedroom. One day he found an old box TV that someone had thrown into the dumpster around the corner and he carried it back and plugged it into the exterior outlet and there he was in his living room, leaned back in the big plush-leather recliner with his feet up on the dark brown ottoman with the brass buttons, watching TV.

David Denny would lie there on the concrete looking in, a thin pane of glass the only thing separating him from his fantasy.

***

Some two decades later, David stands at the bedroom window of his apartment, looking through the glass at the street outside. His apartment. That still sounds strange. He woke up confused that first night, wondering where he was. It took him a few ticks to remember.

Everything had moved so damn fast. After years of crawling at an impossibly slow pace, the system had lurched into hyperdrive. Just two and a half weeks after he had first gone down to the Pathways to Housing office, there he was signing the lease on a government-subsidized apartment. The folks at Pathways all told him they couldn’t remember anyone else getting into housing that fast.

Standing at the window, David doesn’t have to look far for a reminder of how far he’s come. He raises his eyes to the squat, red-brick building across the street, the last of the block’s abandoned structures awaiting renovation. Boards cover the empty windows, and dry, brown vines climb the near corner as if they’re looking for somewhere else to go.

“Damn,” David thinks, squinting back into a past that seems both far and near. “I used to be homeless there.”

***

Before those nights outside the furniture store, before that bit of time when he would curl up on a bench across from TGI Fridays, after he’d slept behind the church over on Tenley Circle, David had spent his nights in that red-brick abandoned building. If he worked the plywood enough to slip through the window and he set up in a room far enough back to where the cops wouldn’t see the light as they drove by, it was an okay spot to spend the night. Of course, he didn’t have electricity or running water, and the furniture wasn’t much to speak of: banged-up milk crates as tables and chairs, dingy cardboard laid out as a mattress, a coarse movers’ blanket bunched into a pillow. He shared the building with its other tenants: cockroaches, rats and raccoons. One night he woke up face-to-face with a wild-eyed possum — he stayed frozen, locked in a primal staring contest, until the thing slunk back into the darkness.

One night he wrote a poem.

The stench emanating from unwashed feet,

In abandoned buildings on a dead street.

No place to even lay your head.

A cardboard box, your only bed

The cold morning air and ceiling leaks,

Stirs alcoholics, dope fiends, and crackhead freaks.

Milk crates strewn about used as chairs,

While some replace the missing stairs.

Off to panhandle the middle class,

Through dope needles, stems, and broken glass.

Not all the memories of his time on the street are awful. A true poet, David has always been able to find moments of beauty among the darkness. He remembers the view from the spot where he used to sleep up on Prospect Street, the yellow, green and blue lights of downtown Rosslyn glittering across the black Potomac. He remembers back when he stayed behind the Catholic church, how the nuns would leave him coffee and coffee cake in the morning, always careful to make a quiet noise so he’d wake up before it got cold.

His love of poetry came from his father, a retired Army man who moved his family to D.C. in 1959 to take a job with the post office. David’s earliest memory from that time comes from a black-and-white photo, now lost, of him and his mother dressed in all white, holding hands in front of the Capitol building. He could walk over to the old Penn Theater with a dollar and buy a movie ticket, cookies, popcorn and a box of Milk Duds and still have money left over to ride the bus home. He remembers his paper route and the shops on the corner and the friendly neighbors.

That all changed when the city decided to build a new bridge on their land and showed up with the eminent-domain papers. David’s father had to move his family across town to Simple City, a neighborhood notorious for its crime and poverty. David’s idols changed— instead of looking up to sailors and Marines, he looked up to the dope dealers who drove by in their long, shiny Cadillacs. It didn’t take long for him to be pulled in.

Prison is where David’s love for poetry flourished. While the cell walls closed in around his body, his mind escaped. He spent hours reading and writing. He borrowed a dictionary and thesaurus from the library and flipped through them every time he came across a word he didn’t know. He graduated from a prison GED program and started teaching eighth-grade math to other inmates. He earned a gig as a clerk for the warden, who took such a liking to him that David worried the other inmates would resent him for preferential treatment.

But David couldn’t stand the halfway houses. Five times he was put into a halfway house to finish out a sentence. Five times he ran and ended up back in prison. The last time he got locked up, he insisted he be able to complete his sentence in prison instead of leaving for a halfway house. That removed the temptation to run, but it also took away the support of a re-entry program and left him fending for himself after release.

When David stepped off the prison bus in 2009, he had no support system, no job prospects and nowhere to go. It would be nearly nine years before he found a home.

***

He didn’t believe it when he got the phone call. Not 24 hours after he sat down with those folks from Pathways to Housing, they called asking if he wanted to go look at apartments. He had been on the list for a housing voucher for years without progress and then, all of a sudden, he was touring apartments. It felt like he’d clicked his heels together three times.

That was just a joke he told, of course, but his path home felt just as fantastical as that of Dorothy and her red slippers. He had sat through meetings where they asked him a bunch of questions like, “How many times have you been homeless?” and they had plugged his answers into some algorithm that spit out a number called a Vulnerability Index that ranked him against other people who needed housing. His social worker had tried to get him placed before — after all, he had those severe bouts of depression and the nerve damage in his legs — but it hadn’t worked. Until he went to Pathways. His social worker said it was like trying to get through a fence. They tried other gates that hadn’t budged; they tried the Pathways gate and it swung right open.

However it happened, David knows it was just in the nick of time. With his legs being the way they are, he figures he wouldn’t have lasted much longer on the street. The shooting pains started a couple years back and have only gotten worse. The doctors are stumped. At first they said it was vascular, then they thought it was neurological. He’d been through ultrasounds and diabetes tests and more doctor’s appointments than he can remember. His team at Pathways takes him to and from those appointments, which is good, because it’s harder for him to get around these days.

One of the doctors recently mentioned a new theory. He said that perhaps the pain is a physical manifestation of psychological trauma, that it could somehow be caused by his depression. David doesn’t buy that, but he is certain of one thing: whatever’s wrong with him was caused by all those years on the street.

***

David turns away from the window, the one framing the red-brick building and a difficult past, and shuffles across his bedroom. He has his own furniture now: a queen-sized bed and chest of drawers, a dinette table and chairs in the dining room, a sofa and large coffee table in the front room. Sometimes he smiles and thinks about that Billie Holiday lyric, “God bless the child that’s got his own.”

Not that housing has cured everything. Each step across the hardwood floor of his bedroom is a painful reminder of the nerve damage in his legs. The memories from all those years on the street still weigh heavy as he comes to the window on the other side of the room.

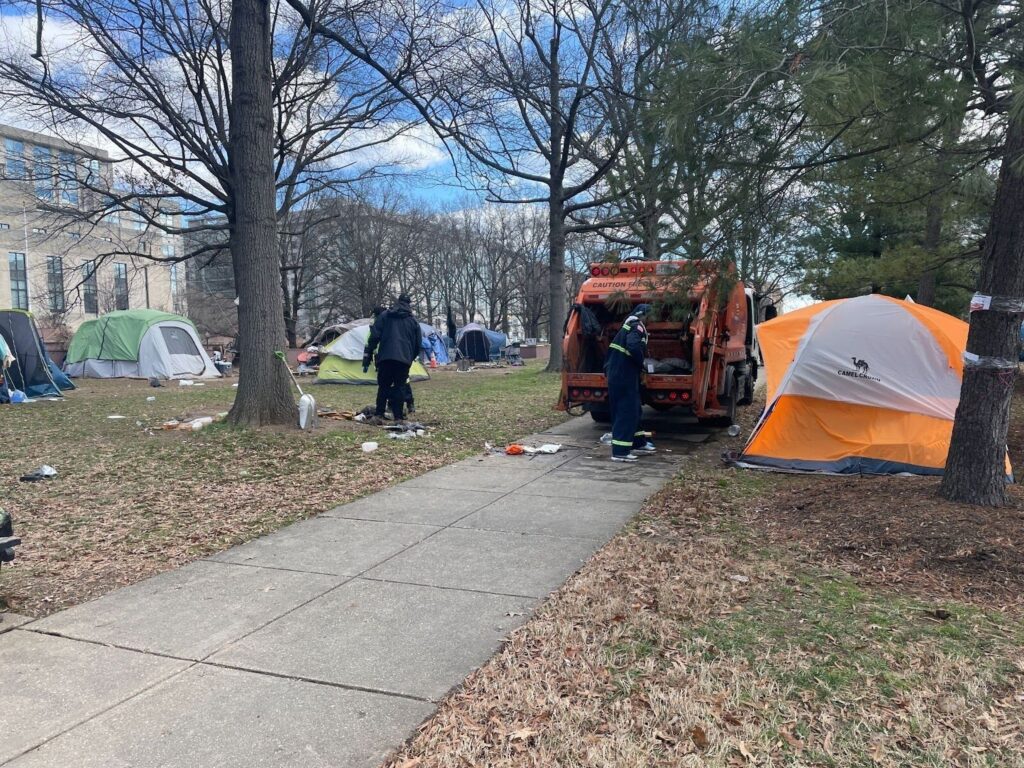

He looks out of this window more than the other. It faces east, overlooking the green field of a city park. A cool, clear stream gurgles gently through the center and a small foot bridge provides a walking path across.

David stands at this window and thinks about the future.