Why doesn’t the American Criminal Justice System work? Community and government leaders joined computer programmers in an attempt to answer that question at Impact Hub DC on June 4.

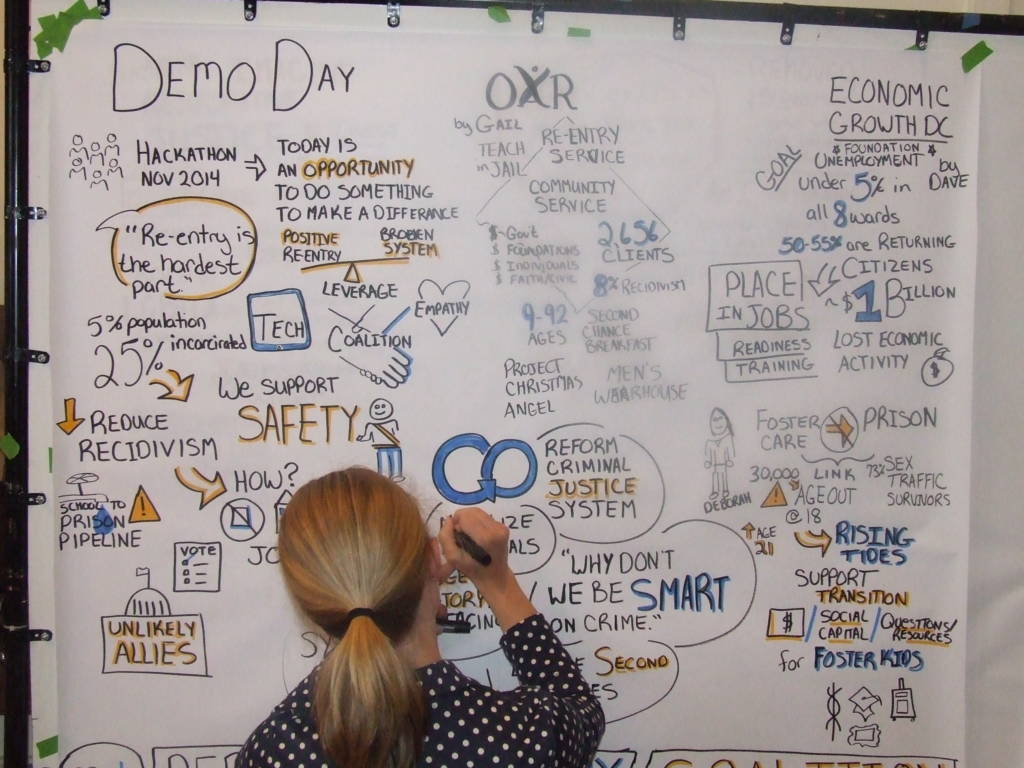

Last November, a Rebuilding Re-Entry “hackathon” was sponsored by Mission: Launch to reduce the barriers previously incarcerated citizens face when returning to society. Civic hackathons–a growing trend since the early 2000s–gather and mobilize diverse groups of professionals to develop tech solutions for a chosen problem. “Demo Day” presented the technological advances achieved for Rebuilding Re-Entry since November.

“America has 5 percent of the world population, but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners” opened Laurin Hodge, executive director of Mission: Launch.

Mission: Launch was started by Hodge when her mother, Teresa Hodge was released from prison. Teresa was imprisoned for nearly six years after pleading guilty to a white collar, non-violent, first offense crime. Mission: Launch aims to help ex-offenders assimilate to society.

Demo Day focused on three main solutions; a website that makes it easy to figure out if the previously incarcerated citizen qualifies for expungement of their record, an information directory of service providers for ex-offenders and a digital job board specific to returning citizens.

In addition to many offenders being imprisoned for “too long,” ex-offenders have a hard time once they are out of prison.

“Re-entry is too often the hardest part,” Hodge said. A series of speakers illustrated this reality and identified problems in the criminal justice system far beyond the means of a hackathon.

The Landscape of Entry and Re-Entry

Employment is the best way to fight the pattern of ex-offenders re-offending and being sent back to prison, offered Dave Oberting, executive director of Economic Growth D.C.

William Cobb was hired and fired “a dozen of times” before he learned that you cannot be fired over past criminal history. He went on to found Redeemed PA to show ex-offenders this and other rights they are entitled to.

“Do you know that we have rights?” Cobb asked another ex-offender at Demo Day, “Do you know that people can’t just discriminate against our population because we have a criminal history?”

Once prisoners are released, many become homeless.

“In fiscal year 2014, 104 ex-offenders in our program were homeless,” said Gail Arnall, executive director of Offender Aid and Restoration in Arlington. “59 of them got housing assistance.”

With tensions over police brutality at a high point in American history, the entire justice system is under strict scrutiny.

“It seems ludicrous that we tell people that ‘we want you to be involved in our society,’ then don’t give you the tools to do it,” said Nicole Austin-Hillery, keynote speaker at Demo Day and employee of the Brennan Center for Justice.

The Brennan Center recently asked 15 presidential hopeful candidates what their plans are to reform the justice system. Answers ranged from the importance of community policing to ending “one-size-fits-all” sentencing.

“But plainly, our nation has too many people in prison for too long–we have overshot the mark,” former President Bill Clinton said in the study’s foreword.

The foster care system almost pipelines kids from foster care to prison, according to Deborah Bey of Digital Humanitarian.

“80 percent of people in prison have gone through the foster care system,” said Bey, who had gone through foster care herself.

One in four young people have a parent locked up, according to Patrice Lee, Generation Opportunity’s Director of Outreach. She believes that some current legislation also turns non-violent, low risk offenders into repeat offenders – keeping them locked up.

“It’s ridiculous that African Americans are 15 times more likely to get locked up than their white counterparts,” Lee continued.

Despite the work of each service provider gathered at Demo Day, the conclusion remained that rebuilding a life is near impossible.

Square One

William Mack, a vendor for Street Sense, was incarcerated for the last six months. He was jailed for vending without a license, and a probation violation. Mack describes prison as a lot of chaos and confusion.

He was released into the custody of Hope Village on April 14, a halfway house with a reputation of being less than helpful.

Mack agreed with the reputation, and believes that Hope Village did little more than pass him along to the next program, the Court Service and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia’s re-entry sanction center.

His initial meeting with a case manager at Hope Village consisted of advice to get a job and stay out of trouble, according to Mack.

Mack believes that all of the options and technologies discussed at the Hackathon could work; however, he did not want to put his full support behind any one idea. He eagerly left Hope Village at the beginning of June, and is excited to restart his life.

“I’m ready to live, man, I’m ready to move forward,” he said.