Since arriving in Washington in 2013, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) has found common ground with some of his most conservative colleagues, including Jeff Sessions and Lindsey Graham.

Despite his reputation as a bipartisan champion, some of Booker’s recent proposals are distinctly progressive. In October, he introduced legislation that addresses environmental injustice such as lead poisoning in low-income communities, which he characterizes as “environmental racism.” This particular bill, however, lacks Republican support and is not anticipated to reach the Senate floor. Skypos Labs, an artificial-intelligence company that specializes in big data, forecasted a 6 percent chance for Booker’s Environmental Justice Act of 2017 to be enacted.

There have been murmurs of a 2020 presidential campaign swirling around Sen. Booker. While he dodges the question here, his ambition is evident. The senator did stints at Stanford, Oxford, and Yale universities before being elected to Newark, New Jersey’s city council, and he eventually served two terms as that city’s mayor. From here, the presidency would be a logical next step.

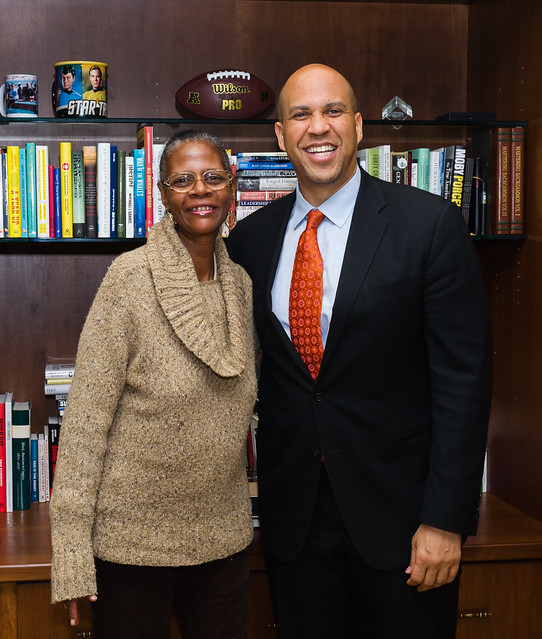

In this interview, conducted by Street Sense Media vendor and contributor Aida Peery, the theme of empowering low-income communities of color arises in each of the issues he speaks most passionately about. Booker calls the criminal justice system “broken,” and its reform is what informs much of his legislative agenda, including a push to legalize marijuana. While he has found cross-aisle cosponsors in bills addressing those issues, it is the senator’s progressive idealism regarding income inequality, criminal justice and health care that shines through in this candid interview.

Last month you introduced the Environmental Justice Act 2017 to protect minority communities from environmental injustice. When my daughter was going to Bernard Elementary School here in Washington, D.C., in the 2000s, I explained to her that she couldn’t drink out of the water fountains at school because we thought there might be lead in the old pipes. How does the bill address issues like these facing working-class communities?

Booker: Most people don’t understand that, Flint, Michigan, is not an anomaly. There are over 3,000 jurisdictions, according to Reuters, that have blood-lead levels twice that of levels found in Flint. This kind of environmental poisoning is going on all over our country, from the water to the air to the soil. I saw it when I was mayor of Newark: from the Superfund site* in our community all the way to when I did urban farming. We turned a city block into a farm for the community, and the state environmental agency wouldn’t let us plant in the soil because they said, “Your soil is toxic,” so we had to use planter boxes.

To me, this bill is really important to give communities the power to fight back. Unfortunately, the communities where you see environmental poisoning are often vulnerable communities, in communities of color. It’s a level of environmental injustice and environmental racism that we should not accept in the United States of America. That’s why I introduced this piece of legislation.

*A Superfund site is an area contaminated by hazardous waste that the EPA has designated for cleanup.

In the bill, is there anything about trying to change the pipes?

Booker: I’ve supported a lot of infrastructure bills to give communities the resources to change their pipes. Supporting legislation directly aimed at giving communities the money to replace pipes and prevent the poisoning has been a big effort of mine. This bill will give people the ability to hold folks accountable, to sue folks who have done the poisoning.

I’m looking for work, and I’ve tried very hard to get a good job in my neighborhood. How do we get employers to pay everyone what they’re worth and hire from their local community?

Booker: The reality is simple. We need to be a nation that pays living wages for a hard day’s work. In the 1960s, the minimum wage was set at a level where someone could raise a family and meet their minimum basic needs of housing and health insurance. The American bargain worked. Right now, in America, we haven’t seen the minimum wage keep up with inflation. Jobs, unfortunately, don’t pay what I consider a living wage, which includes sick leave, savings for retirement and ultimately a salary where you can afford housing. I’d like to raise it to $15 an hour and peg it to inflation so that we don’t have to continue to have this fight every few years to raise the minimum wage.

This is about getting back, not to handouts, but to saying that if you’re willing to work in America, you should be able to meet your minimum basic needs. I have a very good friend named Natasha Laurel who works at an IHOP. She works a full-time job and catches extra shifts when she can, but she still has to rely on food stamps and public housing. So really, that corporation is outsourcing the cost of their labor on the rest of us, because it’s the public that has to now pick up the minimum needs of that family. Well, that’s not fair. That corporation should be paying the full cost of their labor. If we can get to a system like that, I think we’d find a lot more justice.

What about prices? Can’t prices stop rising for a certain amount of years so when the people do get $15 they will be able to catch up?

Booker: Prescription drugs, cost of education, child care, rent. All these things are going up, but people’s wages are not. We should be taking on the issue of high-cost pharmaceuticals. I’ve joined with a lot of other Democratic senators on a number of pieces of legislation that could help us drive down the cost of pharmaceuticals. We also need to drive down the cost of childcare. We should, as a government, understand that investments in childcare and early-childhood education aren’t giveaways. They’re actually investments in the future of this country.

I have a book club and we just read “Evicted,” which is this incredible book about Milwaukee that talks about the eviction problem. Ultimately, to society, a little bit of money to stabilize a family actually returns so much more in terms of the potential cost for when that family does get evicted, especially what it means to children.

We make very bad economic decisions in this country. We feel so much more comfortable to pay much more on the back end of a problem as opposed to investing in people on the front end, when the costs are so much lower. We see this in medical costs as opposed to investing in preventative care, investing in dealing with people who have chronic illnesses, managing their illnesses. We’d rather pay much more when the problems become far more acute.

We have a lot of homelessness in D.C. What are you and your colleagues going to do about homelessness and building up more housing for all?

Booker: The housing crisis hasn’t recovered since the great recession. When I was mayor of Newark, one of the biggest challenges was getting the resources to create and build more affordable housing. It’s something that our country hasn’t had a commitment to, and we’re doing it at our own detriment.

One of my favorite housing organizations is called Plymouth Housing Group, in Seattle. They did a study where they looked at 23 homeless people. They found out that despite how expensive supportive housing was, by putting the 23 people in supportive housing, they were saving taxpayers about $1 million. Often when you’re on the streets, things happen: You end up in emergency rooms, which is really expensive, or you have run-ins with police and might end up in a jail, which is awful for both the person that’s in jail and the cost of that is egregious, when the money could be better invested in empowering people.

[ Read more: Dr. Dennis Culhane’s 8-year study found an economic argument for providing permanent supportive housing ]

I saw this in Newark when we started targeting housing for specified populations, whether it was women who were coming out of domestic violence situations, veterans, or families who were struggling with HIV/AIDS. By raising philanthropic dollars to help homeless folks in our community, we were actually getting a win-win. A win for the homeless person that’s in housing, and a win for society as a whole by creating a more just, smarter society that was investing in people on the front end, as opposed to problems on the back end, which often costs more.

As a senator for the past four years, who knows how hard it is, I’ve been fighting to support programs like tax credits that incentivize the building of affordable housing and Section 8 dollars, which are really critical for public housing in urban communities.

What is the government going to do about the parole system? For instance, I’ve known a lot of Black men who have come out of prison but still are on life parole even when they’re doing well. Why would someone have to come out of prison and be on parole for life?

Booker: I’m the only United States senator who lives in an African-American community in the inner city; in fact the median income in my census tract in my neighborhood is about $14,000. So I live in a community that has been severely impacted by a broken, cancerous criminal justice system. Remember, there’s no difference between Blacks and Whites for drug use or even drug selling, but African-Americans are about four times more likely to be arrested and ground into this system.

You’re right. You [might get] a lifetime sentence, and when you get out of prison, and you’re on probation or parole, 20 or 30 years from now you can’t get a Pell Grant, you can’t get public housing, you can’t get…

You can’t get anything!

Booker: You’re right. And so literally, for the rest of the person’s life, you strip away much of their ability to compete economically in an already tough economic system that already works against you if you’re poor in America.

We all swear an oath to this ideal of liberty and justice for all. But you and I live in a community where we see clearly that the justice system for people who are poor, often minority, is very different than the justice system for people of privilege. My friend and hero Brian Stevenson, [a lawyer and social-justice advocate in Alabama,] says that we have a justice system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.

Communities of color are bearing the brunt of arrests for things that two of our last three presidents admitted to doing. Presidents Bush and Obama didn’t just do a little marijuana; they did serious, felony drug use. We’ve got to make sure this system works for everybody and doesn’t do more harm than it does good.

I believe in this ideal of restorative justice, that our justice system should hold people accountable. It should be equal for everybody. Ultimately we do our society a disadvantage when we’re not using those times of incarceration to empower somebody to be better than they were. We do something like stripping away educational opportunities from people in prison, which is a horrendous, self-inflicted wound, because we know that every dollar we spend on helping people get their education while in prison then gets returned to us by their success when they get out.

Back in the ’70s, we used to have the whole health-care package: eye, dental, health. Over the years it’s gotten broken up into many packages. Now it’s the deductibles and copayments. How would you reform Obamacare if you had no resistance?

Booker: I grew up in the system, too. My parents worked for IBM. They didn’t have any limitations on their ability to take my brother and I when we got sick or had an accident. We made this major stride with Obamacare in seeing the rates of uninsured drop in our country. I would very much like to see some kind of public option like Medicare for all, and people would be able to opt out of that system and buy [private insurance] if they have the means.

There are still many people without health insurance. There are still many people who make tough decisions about whether to afford their prescription medication or afford their rent. We still have an incomplete system. Other countries are looking at us and thinking, “Wait a minute, you guys saddle your businesses with these costs? You guys saddle people with these costs?”

It should be a fundamental right in this country. Fundamental right. You cannot have life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness without health care. I look forward to the day when we look back at the system the way it was and think, “How could we have denied our citizenry access to affordable, quality healthcare?”

Are you going to run for president? I think you’d be a great president.

Booker: I’m going to hug you for saying that!