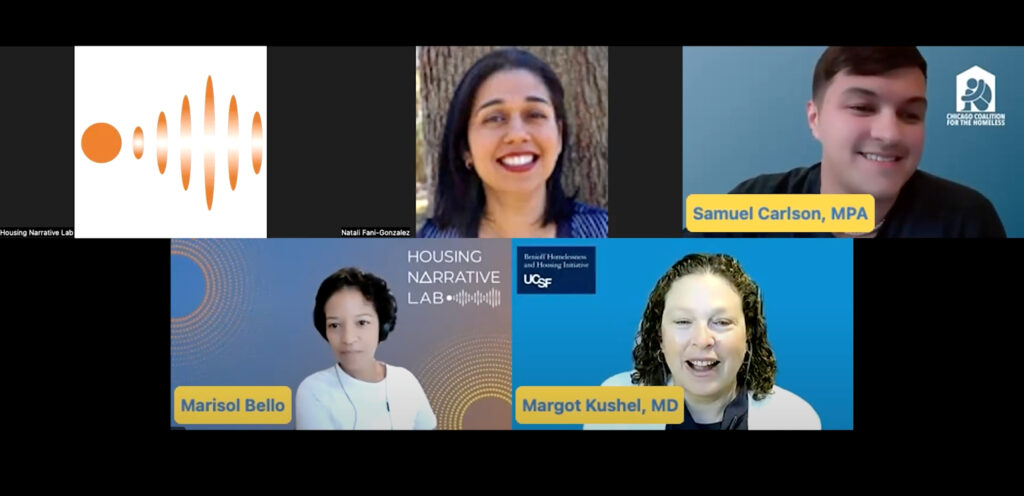

The Housing Narrative Lab, a D.C.-based communications research hub providing support to organizations working to end homelessness, hosted a Zoom webinar on June 10 to discuss the ways journalists get the story of homelessness wrong.

Marisol Bello, director of the lab, moderated the event. Panelists included Dr. Margot Kushel, the director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative; and Sam Carlson, manager of research and outreach at the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. The event detailed common ways the media and data fail to provide a complete picture of homelessness.

For instance, when journalists cover homelessness, they often focus on its visible forms, like people living in tents on street corners, Kushel said. Journalists are less likely to tell more hidden stories of homelessness, like taxi drivers sleeping in their cabs.

“Each of them is deserving of our help, our compassion, our lack of judgment, but one of those stories gets told a lot more than the other one does,” Kushel said at the webinar.

Kushel and Carlson explained the drawbacks of the Point-in-Time count, a popular data set used by cities, journalists and organizations as the basis for services offered to the homeless community. One night each year, volunteers count the number of people experiencing homelessness.

“With that, it fails to account for those temporarily staying with others or those not experiencing homelessness at that point in time,” Carlson said. “Point-in-Time methodology dramatically undercounts homelessness, and worse, points to the wrong policy solutions.”

In D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser announced in April a record low number of people experiencing homelessness based on this year’s count. While Bowser celebrated this decrease, it may not be accurate, panelists said. Point-in-Time counts are “more likely to count the people who are visibly homeless,” Kushel said.

Kushel and Carlson conduct research on homelessness in their respective cities, and they work to ensure a representative count by looking for the people who are not visibly homeless. Carlson emphasized the importance of counting people temporarily staying with family or friends, also known as doubling up.

“The vast majority of these families are staying wherever they can. They’re often forced to move frequently between unstable living situations like sleeping in motels, cars, trains or temporarily staying with others,” Carlson said. “I can’t underscore enough that homelessness is not as linear as what’s seen in the public.”

The pair also highlighted some causes of homelessness the public overlooks. Through her research, Kushel discovered that the death of a parent was a common cause; if the lease is in a parent’s name and the parent dies, their children often face eviction. Updating end-of-life practices, like adding another name to the lease, “is an incredible opportunity for prevention,” Kushel said.

The Vulnerability Index – Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (VI-SPDAT), which providers use to determine who receives homeless services, is another example of how current data-driven solutions can misinterpret the causes of homelessness.

“The problem with how we prioritize homeless services is that we base your priority for services … on those individual vulnerabilities, which is going to disadvantage people who don’t have those but who are homeless because of these larger societal forces,” Kushel said.

Kushel pointed to the ways structural racism, like Black families being excluded from buying property and accruing wealth, has pushed people into homelessness at a higher rate than mental health and substance use problems, which often receive more attention from support organizations.

Affordable housing is the answer, Kushel said.

“We need to solve that underlying problem. We need to stop focusing on mental health and substance use as the drivers. They are not,” Kushel said. “The driver of homelessness is this dramatic shortage of extremely low-income housing.”

In the District, there are 40,000 people currently on the D.C. Housing Authority waitlist. According to 2020 data from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there is a shortage of more than 27,000 affordable units for low-income renters across the District.

Carlson said the way to bring change is through “political will and the public awareness of the issue.”

Research shows that people facing chronic homelessness have found and retained housing through “supportive housing,” which includes subsidized housing, case management, drug and alcohol treatment, and medical treatment, Kushel said.

“We know what to do. We just lack the political will to do it, and we’re telling the wrong stories,” Kushel said.